U.S. Health Care: The Free-market Myth

Many critiques of U.S. health care begin with the assumption that, as The Economist put it, the United States is "one of the only developed countries where health care is mostly left to the free market." Dr. David Blumenthal, a former advisor to President Barack Obama, told the New York Times in 2013 that in the United States, "we like to consider health care a free market." That assumption gets the situation backward: In truth, among wealthy nations, the United States may have one of the least-free health-care markets.

In a free market, government would control 0% of health spending. Yet the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) reports that in the United States, government controls 84% of health spending. In fact, government controls a larger share of health spending in the United States than in 27 out of 38 OECD-member nations, including the United Kingdom (83%) and Canada (73%), each of which has an explicitly socialized health-care system. When it comes to government control of health spending, the United States is closer to communist Cuba (89%) than the average OECD nation (75%).

Nor does the United States have market prices for health care. Direct government price-setting, price floors, and price ceilings determine prices for more than half of U.S. health spending, including virtually all health-insurance premiums. Moreover, government pushes all medical prices and health-insurance premiums upward through tax laws and regulations mandating that people purchase excessive levels of health insurance. The extra coverage reduces patients' price sensitivity (i.e., their willingness to shop around for lower prices), which allows providers to charge higher prices. The myth that the U.S. health sector has "largely unregulated prices," as the Los Angeles Times reported, is as stubborn as it is outrageous.

That myth goes hand-in-hand with another: that government price-setting always pushes prices below market levels. If U.S. medical prices are excessive, this myth implies, those prices must be market prices. Government intervention can indeed lead to below-market prices, which create shortages and reduce quality — the U.S. government sets price ceilings of zero dollars on transplantable organs, for example. More often, however, federal and state governments push health-care prices higher than they would be in a free market. U.S. health-care prices are excessive because government controls them.

If health care in the United States operated under free-market principles, it would deliver more-universal health care. A closer look at how government distorts and inflates health-care prices demonstrates why.

GOVERNMENT PRICE-SETTING

Government-set prices control more than half of U.S. health spending. Medicare, Medicaid, and other government programs account for 48% of such spending, while out-of-pocket spending subject to Medicare price-setting accounts for another few percentage points. When government is the buyer, political rather than market forces determine prices.

In terms of dollars, the traditional "fee-for-service" part of Medicare is the single-largest purchaser of medical care in the world. Each year, Medicare sets prices for 10,000 distinct physician services across 112 different "payment localities," whose borders federal regulators also draw. Traditional Medicare has 20 such price-setting schemes for various types of facilities and suppliers. Tom Scully, head of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services during the George W. Bush administration, described the $1 trillion program as "a big, dumb price fixer." As for Medicaid — which spends nearly another trillion dollars — each state sets its own prices for as many distinct services.

When government programs aren't directly purchasing medical care, they pay for health insurance on enrollees' behalf. More than 50% of eligible Medicare enrollees, 75% of Medicaid beneficiaries, and all who enroll in Obamacare have government-subsidized "private" coverage. In these cases, government controls two prices: the price that each enrollee pays, and the total price the insurer receives for that enrollee.

Traditional Medicare's pricing errors, including excessive prices, are as ubiquitous as they are intractable. One of the more striking indications of widespread mispricing is that Medicare routinely sets different prices for identical items depending solely on who owns the facility. For instance, Medicare pays ambulatory surgical centers (ASCs) $1,000 per cataract surgery with intraocular lens insertion but pays hospitals $2,000 for the same procedure. In Overcharged: Why Americans Pay Too Much for Health Care, law professors Charles Silver and David Hyman note:

In 2012, Medicare paid an average of $1,300 for colonoscopies performed in doctors' offices, but it shelled out $1,805 — 39 percent more — when these procedures were delivered at hospitals....When a hospital gives a lung cancer patient a dose of Alimta, its fee is about $4,300 larger than a doctor with an independent practice would receive. For Herceptin, a drug given to women with breast cancer, the site-of-service differential is about $2,600. And for Avastin, when used to treat colon cancer, it is $7,500.

These are far from the only examples.

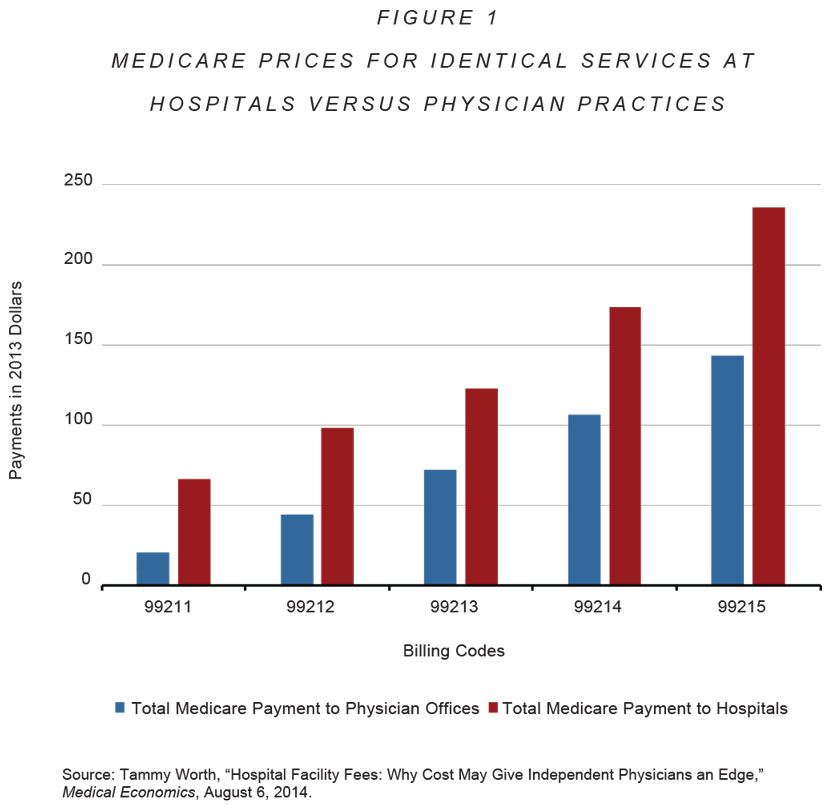

Differences in quality, consumers, convenience, and cost cannot explain why Medicare sets varying prices for the same service. In 2014, Medicare paid long-term care (LTC) hospitals about three times as much as skilled nursing facilities — $1,400 per day versus $450 per day, a per-admission price differential of about $30,000 — to provide similar services to similar patients, without any evidence of additional benefit. Medicare sets and pays higher prices for evaluation and management appointments that occur in hospitals than those that occur at physician offices (see Figure 1 below), even though these patients do not need hospital-level care nearby. When a hospital purchases a physician practice or other facility, Medicare increases the prices it pays for the same people to provide the same services to the same patients in the same location. At times, Medicare sets higher prices for facilities that have lower input costs and less costly patients.

As these examples suggest, Medicare routinely sets prices well above cost. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services admitted as much in 2018. "The Medicare program," it reported, "pays nearly twice as much as it would pay for the same or similar drugs in other countries."

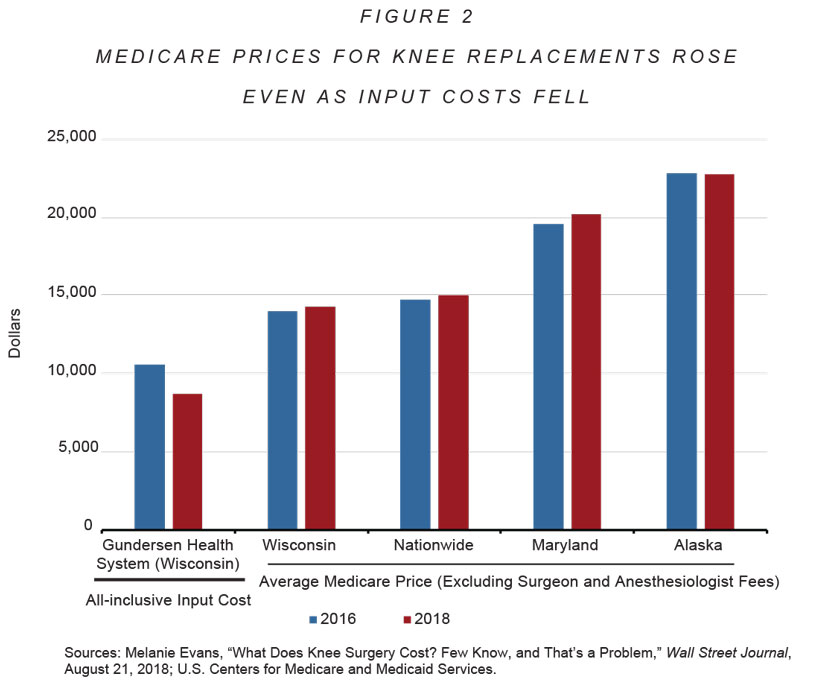

Gundersen Health System in Wisconsin illustrates how Medicare persistently sets prices well above cost. Gundersen's all-inclusive input cost for knee replacements in 2016, according to the Wall Street Journal, was "at most" $10,550. The average Medicare price — even after excluding surgeon and anesthesiologist fees — was higher in all 50 states. In Wisconsin, it was around $14,000. By 2018, Gundersen had reduced its input costs by 18%, to $8,700. In a competitive market, prices would likewise fall. But the average Medicare price rose, both in Wisconsin and nationwide. (See Figure 2 below.)

The proliferation of physician-owned specialty hospitals is due largely to entrepreneurial physicians trying to capture the excessive prices Medicare conjures and pays for many procedures. In the early 2000s, Tom Scully explained how to spot excessive Medicare prices: "[A]ll of a sudden you start seeing ASCs pop up all over the place to do colonoscopies or to do outpatient surgery." Obamacare subsequently banned Medicare subsidies to new physician-owned hospitals, a consequence of general hospitals' lobbying to keep those excessive payments for themselves.

State-level price regulation also appears to push prices above market levels. A 2016 study of acute-care hospitals found that those located "in states with price regulation...tended to be more profitable than other hospitals." The World Health Organization and the OECD concurred in a 2019 report: "Studies conducted in the USA generally conclude that price setting by a regulator...improved hospital financial stability." If government price regulation restrained prices, we would expect to see the opposite.

As if traditional Medicare's prices weren't excessive enough, the prices Congress sets for "private" Medicare Advantage (MA) plans leave taxpayers paying an average of 20% more every time an enrollee switches from traditional Medicare to MA. The fact that enrollees can increase their Medicare subsidy by switching helps explain why more than half of beneficiaries now choose MA.

Despite researchers' general acknowledgment of the problem, Medicare's pricing errors often exhibit greater longevity than Medicare enrollees. The U.S. Federal Trade Commission and the Department of Justice have complained about Medicare's "site-of-service" pricing errors for at least two decades. In 2018, Medicare's price-setting advisory panel — the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission — confessed it has a "long-standing concern" that Medicare sets prices for procedure-based specialists and radiologists too high relative to primary-care physicians.

Government price-setting not only raises prices in government programs, it also pushes private prices higher. Indeed, excessive private-sector prices are due in no small part to government subsidies and price-setting.

Medicare and Medicaid often set the prices they pay for drugs at a percentage of whatever manufacturers charge private payers. Those price-setting rules lead manufacturers to increase private-sector prices, since doing so means they receive more money from those programs. One 2006 study estimated that Medicaid's drug-pricing rules increased private-sector prices by 15%. The way Medicare sets prices for physician-administered drugs creates the same incentives.

In addition, Medicare and Medicaid encourage higher private prices by making enrollees less sensitive to prices. When providers raise prices on price-sensitive patients, they tend to lose business. The resulting revenue losses discourages price increases. Medicare and Medicaid, however, create large pools of price-insensitive patients on whom providers can draw to replace that lost revenue. When providers have market power — which, due to hospital and physician-group consolidation, is increasingly the case — Medicare and Medicaid encourage them to charge higher prices to private payers because these programs' price-insensitive enrollees reduce the resulting revenue loss to providers.

Providers object by insisting that Medicare and Medicaid actually set prices too low, which then forces them to increase prices for private payers — a practice providers and their lobbyists call "cost-shifting." But economic theory suggests the exact opposite is true: In the presence of provider market power, government purchasing increases private-sector prices, which then move in the same direction as the government-set prices.

Empirical research confirms the theory. One study in 2017 estimated that "a $1.00 increase in Medicare's [physician prices] increases corresponding private prices by $1.16." The study also found that if Medicare were to increase physician prices by 1%, private-sector spending would rise by nearly three times as much as Medicare spending ($3.5 billion versus $1.3 billion per year, respectively). Conversely, reducing Medicare or Medicaid prices would lead providers to reduce private prices.

Government is not a competent price-negotiator, much less a skillful one. It sets the prices it pays higher than markets would, then pushes private-sector prices higher still. That Medicare prices can simultaneously be about 60% lower than private-sector prices yet still be excessive testifies to how wildly government increases health-care prices.

INSURANCE PRICE CONTROLS

Ever since Obamacare took full effect in 2014, nearly all health insurance in the United States has been subject to federal price controls that restrict or eliminate insurers' ability to vary premiums according to an individual's health risk. Rather than allow markets to set premiums according to risk, "community rating" price controls impose a price floor on premiums for the healthy (at whatever the insurer charges the sick) and a price ceiling on premiums for the sick (at whatever the insurer charges the healthy).

When price floors require insurers to charge healthy consumers premiums higher than what they cost to insure, insurers become especially eager to sell to those consumers. Yet higher premiums also make healthy individuals less willing to purchase insurance. Government "solves" the latter problem with subsidies that force taxpayers to shoulder the excess premiums. This is the purpose of Obamacare's premium subsidies. A similar dynamic occurs in Medicaid and MA, where government sets the prices (premiums) it pays private insurers above what it costs to cover healthy enrollees. In each case, insurers and brokers then compete to enroll the healthiest patients, since doing so allows them to capture those excessive prices. For example, MA plans attract the healthiest seniors by offering perks such as groceries, pet care, and gym memberships.

At the same time, community rating's price ceilings reduce premiums for the sick, which makes sick patients extremely eager to purchase insurance. But it also guarantees that sick patients as a group will always cost more in claims than they pay in premiums. The result is that community rating effectively penalizes insurers who offer coverage that sick patients find attractive. Insurers must design their policies to be "unattractive to people with expensive health conditions," as Kaiser Family Foundation researchers put it in 2016, because doing so helps them "avoid enrolling people who are in worse health."

Economists have repeatedly observed that community-rating price controls reduce health-insurance quality for the sick. Community rating required insurers providing employee coverage to Harvard University, Stanford University, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and the state of Minnesota to compete to avoid the sick through such means as eliminating comprehensive plans. It also led insurers in the Federal Employees Health Benefits Program and New York's small-employer health-insurance market to compete by dropping coverage for 24-hour nursing care — not because such care is expensive, but because the patients who use it are.

Congress attempts to mitigate the unintended consequences of government price-setting with — you guessed it — more government price-setting. Where government imposes community-rating price controls, it typically also offers "risk adjustment" subsidies to health plans that attract sicker-than-average customers. In 2022, Congress paid insurers who offered MA plans $6,726 to cover a typical 80-year-old male. But if he had diabetes or vascular disease, the plan received additional risk-adjustment payments of $1,284 or $3,620, respectively. Some diagnoses trigger payments of up to $10,000 or more.

The purpose of risk-adjustment subsidies is to bring the total premium an insurer receives for an enrollee in line with the enrollee's expected medical expenses. In other words, risk adjustment is the government's attempt to match the risk-based premiums that would naturally occur in free markets. The reason government attempts to mimic free markets is significant: It is because market prices minimize incentives for insurers to avoid and/or shortchange the sick. As the maxim goes, hypocrisy is the homage vice pays to virtue. In this case, risk adjustment is the homage market opponents pay to market prices.

The problem is that risk adjustment works no better than other forms of government price-setting. Even after risk-adjustment subsidies, Obamacare's community-rating price controls still penalize insurers that offer attractive coverage for infertility (a penalty of $15,000 per patient), multiple sclerosis ($14,000), substance-abuse disorders ($6,000), diabetes insipidus ($5,000), hemophilia A ($4,500), severe acne ($4,500), nerve pain ($3,000), and other conditions. Even with risk adjustment, government still gets the prices wrong.

The result has been a race to the bottom in terms of the quality of insurance coverage for the sick. Risk adjustment notwithstanding, Obamacare's community-rating price controls have caused individual-market provider networks to narrow significantly since 2013, when network breadth better reflected consumer preferences. They have eroded coverage through "poor coverage for the medications demanded by [the sick]" (in the words of a 2019 study); higher deductibles and copayments; mandatory drug substitutions and coverage exclusions for certain drugs; more frequent and tighter preauthorization requirements; highly variable coinsurance requirements; inaccurate provider directories; and exclusions of top specialists, high-quality hospitals, and leading cancer centers from their networks. The erosion in coverage can cost chronically ill patients thousands of dollars per year.

The healthy suffer, too. As that 2019 study put it, "currently healthy consumers cannot be adequately insured against the negative shock of transitioning to one of the poorly covered chronic disease states." A coalition of dozens of patient groups has complained that this dynamic "completely undermines the goal of the [Affordable Care Act]." Risk-adjustment subsidies likewise fail to offset similar unintended consequences in MA.

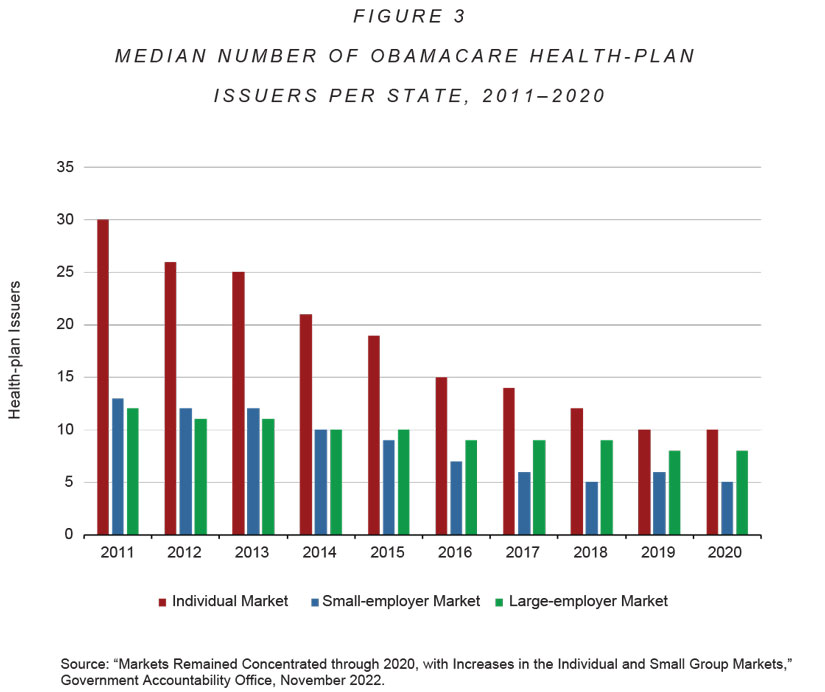

Such price controls further lead to increasingly higher premiums over time. Obamacare doubled or even tripled premiums for many healthy patients. Premiums have risen so dramatically that in 2021, Congress began subsidizing premiums for households with annual incomes of up to $600,000. (Those subsidies lapse at the end of 2025.) A 2017 McKinsey study estimated that community rating, along with Obamacare's ban on excluding those with preexisting conditions, is the primary cause of rapid individual-market premium growth. Community-rating price controls also introduce volatility that favors larger insurers and encourages insurance-market concentration. As a result, Obamacare has led to fewer health-plan choices for individual-market enrollees (see Figure 3 below).

Indeed, community rating causes premiums to rise so precipitously that insurance markets often shrink or disappear altogether. Health insurers have noted that when "Kentucky, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Vermont, and Washington...prohibited risk-based underwriting," these restrictions resulted in "an ever-shrinking market." In some cases, markets "essentially collapsed." Obamacare's community-rating price controls had similar effects in the law's LTC-entitlement program and the private market for child-only health insurance. Lavish taxpayer subsidies appear to be the only thing preventing Obamacare's health-insurance Exchanges from imploding.

REDUCING PRICE SENSITIVITY

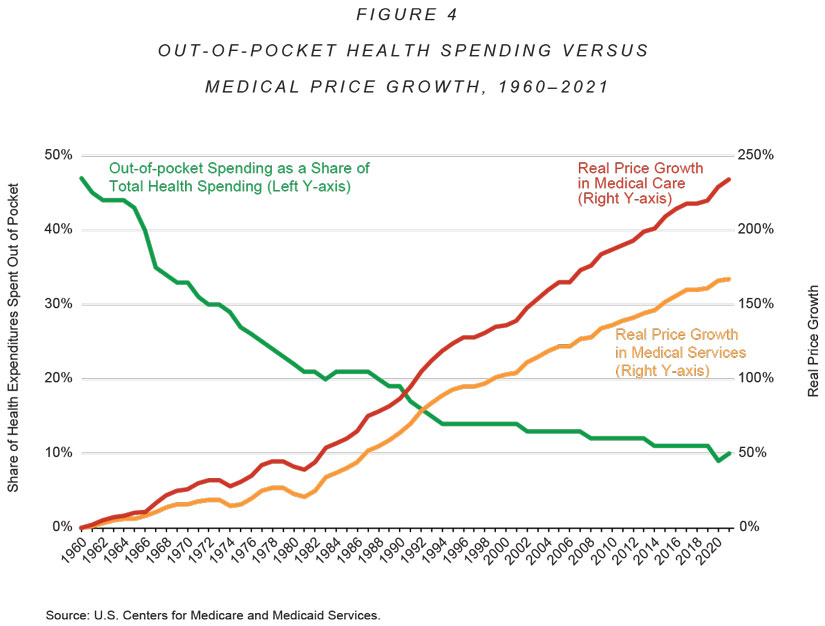

Direct price-setting and health-insurance price controls are not the only ways government distorts health-care prices. Government health-care subsidies, state health-insurance mandates, and sweeping tax incentives for employer-sponsored health insurance further drive prices upward by reducing price sensitivity among patients and price competition among providers. Figure 4 shows that, as patients' out-of-pocket share of medical spending fell between 1961 and 2021, prices for medical care and services rose increasingly faster than general inflation. (Had those prices increased at the same rate as general inflation, the "medical services" and "medical care" curves would lie flat along the x-axis.)

Multiple randomized, controlled experiments have also found that when subsidies cause patient price sensitivity to fall, per-capita health spending rises, which of course increases health-insurance premiums.

Correlation is not causation, but one can observe similar correlations between price sensitivity and prices for specific products. For example, before Obamacare mandated in 2014 that patients purchase 100% coverage for prescription contraceptives, real prices for hormones and oral contraceptives had fallen by 12% from 2009 to 2013. But once the mandate made patients less price-sensitive, prices for hormones and oral contraceptives skyrocketed — rising by 108% from 2013 to 2019, or almost three times the rate of price growth for other prescription drugs.

Research has also demonstrated that the reverse is true: Where patients became more price sensitive when purchasing certain health-care services, prices for those services fell quickly and dramatically — without anyone losing access to care. A series of studies found that within two years of patients' becoming more price-sensitive, prices declined for several procedures, from a 10.5% decrease for MRI scans to a 32% drop for laboratory tests. At high-priced hospitals, prices for hip and knee replacements fell by an average of $10,505 (24%) per procedure — i.e., enough to pay for another knee replacement. The overall average price for hip and knee replacements fell to $27,557, which study authors believe greater patient price-sensitivity could reduce further.

The foregoing examples scarcely exhaust all the ways government controls, distorts, and increases U.S. health-care prices. Indeed, they hardly mention problems at the state level, of which there are many. As of 2018, 35 states had some form of "any willing provider" regulation, which pushes prices upward by preventing insurers from negotiating volume-based discounts from providers. More than 30 states enforce "payment parity" price controls that impose either ceilings on what providers may charge patients or (more often) price floors that increase how much insurers pay providers. Another 30-plus states, along with Congress, have enacted "surprise billing" laws that limit how much out-of-network providers can charge patients and their insurers.

Another means by which government indirectly increases health-care prices is through regulations that restrict supply. States do this in several ways: by barring competent clinicians from providing certain services; by banning high-quality, affordable insurance from out-of-state carriers; and, in many cases, by prohibiting market entry of new medical facilities. Congress, too, puts upward pressure on prices by forbidding new medical goods and lower-priced health insurance from entering the market. The whole purpose of government-issued patents is to encourage innovation via entry barriers that increase prices.

Sherry Glied, a health economist in the Clinton and Obama administrations, wrote in 2021: "There is no reason to believe that current prices provide incentives that reflect either underlying costs or consumer preferences." Medicare alone has allowed pharmaceutical manufacturers, as a 2016 study put it, "to increase prices and capture far more value than they could when facing a market with less insurance and more flexibility." Drug companies profited so much that the program "might have allowed firms to capture more value than their products created." There is simply no excuse for perpetuating the myth that U.S. health-care prices are market prices, or that the U.S. health sector is a free market.

FROM MYTH TO SOLUTION

As those price-sensitivity experiments demonstrate, the ability of freely moving market prices to make health care more universal without central direction is nothing short of a marvel. Making health care more universal will require policymakers to eliminate regulatory and tax distortions of health-care prices, and to remove government from the business of purchasing health insurance and medical care.

The most important step would be to adopt tax and entitlement reforms that let consumers control all $5.6 trillion in U.S. health spending. When 340 million consumers find that they — rather than employers, insurers, or the government — get to keep the savings from price-conscious purchasing, they will spark price competition that will cause prices to plummet and thereby make health care continuously more universal. Insurers and providers will offer consumers what they want — better, more affordable, more secure health care — or go out of business. The government could still redistribute to the elderly, the poor, and the sick. But it would do so as Social Security does: with cash. No more centralized economic planning to drive up health-care prices and reduce health-care quality.

The next step would be to eliminate the reams of regulations that block access to lower-cost, higher-quality health insurance and medical care. Allowing consumers to control all U.S. health spending would sensitize them to the cost of those regulations. That regulatory-price sensitivity would translate into more voter support for eliminating the mandates and price controls that are increasing health-insurance premiums and medical prices in a vicious, never-ending cycle.

Policymakers who set the United States on this road would not be going it alone. Seniors already trust the Social Security model. Government licensing of clinicians adds practically nothing to the quality protections that would remain after deregulation, which include market certifications and the tort system. Many states get along just fine without "certificate of need" regulation. Many countries already recognize other regulators' certifications of drug safety and efficacy. German residents have the freedom to purchase affordable, secure, lifelong health insurance at actuarially fair rates. U.S. territories somehow manage without Obamacare's costliest health-insurance regulations.

The health-care debate is not between one tribe that wants universal health care and another that does not. It is between people who know that making health care universal requires free markets, and those who cannot recognize government failure even when they are drowning in it.