Insuring against Catastrophic Risk

Natural disasters are relatively common across most geographic regions in the United States. Losses from such catastrophic events vary widely over time and significance, however. Hurricane Ian, which struck Florida and other southeastern states in September 2022, caused estimated insured losses of over $56 billion. The Northridge, California, earthquake in January 1994 caused losses of $35 billion; the January 2025 Los Angeles fires, up to $45 billion. Hurricane Katrina, which hit Louisiana in August 2005, caused losses of around $100 billion (in 2024 dollars).

Homeowner's insurance policies typically include coverage of most catastrophe risks. These policies, however, systematically exclude coverage of water damage caused by floods, hurricanes, and cyclones, as well as damage caused by earthquakes. To fill these gaps and others, both states and the federal government offer certain types of catastrophe insurance and assistance to resident homeowners and small businesses.

At the state level, when a certain risk is particularly high in a given area, private insurers may not be able to price policies covering the risk accordingly. Such risks may also be excluded due to regulation or market conditions. State governments respond to these conditions by sponsoring residual insurance programs to provide resident homeowners with "last-resort" insurance for specific risks or multiple perils. Owing to volatility triggered by recent disasters in Louisiana, Florida, and California, these policies' premiums and volume have increased significantly, seeping into the general markets for conventional insurance and reinsurance and contributing to the bankruptcies of some small insurers.

At the federal level, the premier insurance program is the National Flood Insurance Program, which was created by the National Flood Insurance Act of 1968 and is managed by a subcomponent of the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). In addition to insuring against flood risk, the program encourages communities to engage in mitigation efforts to reduce losses from future floods — activities that would be less extensive without federal influence and assistance.

Despite premium collections, current state and federal programs for catastrophe insurance tend to cost governments a significant amount. They also tend to be poorly targeted, as low-income households are less likely to have insurance than those with higher incomes. Coverage limits can be severe, and requirements to carry coverage are generally loose and incomplete. Though there are some efforts to encourage participating communities to mitigate losses, these, too, are incomplete.

Not all losses are insured. According to the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), in 2023, "insurers covered $80 billion of the $114 billion of [homeowner's insurance] losses attributable to natural disasters, meaning that 30% of those losses were not insured." Some of these uninsured losses stemmed from insurance-policy deductibles and co-pays, but most were due to coverage limits or a complete lack of insurance. And although some uninsured losses may be federalized through disaster-relief funds, the remainder represents a large, sudden loss to households — often those with lower incomes.

In certain years, the federal share of losses through disaster relief is much larger, particularly when a catastrophe hits areas and populations that are poorly insured, such as when Hurricane Katrina hit Louisiana in 2005. In 2017, the annual accumulated cost of billion-dollar disasters reached a high of $306 billion, driven mainly by Hurricanes Harvey, Irma, and Maria, with significant federal disaster payments going to Puerto Rico.

There is one more federal catastrophe-insurance program known as the Terror Risk Insurance Program, which was established in the wake of the terrorist attacks that occurred on September 11, 2001. While not perfect, the program has largely achieved its goals and, because terrorism remains a live threat, presumably will be renewed by Congress. This program could serve as a model for replacing state residual plans, federal flood insurance, and federal disaster-relief funds while also extending coverage to all the major risks that households face — including floods, earthquakes, wildfires, hurricanes, tornadoes, wind, and severe hailstorms.

FAIR PLANS

Many state-run insurance programs began as Fair Access to Insurance Requirements (FAIR) plans under a 1968 federal law that established a legal framework for states to encourage insurance coverage. These were intended to address redlining in inner-city communities where insurers did not offer coverage. Today, most FAIR plans address various types of catastrophe risk.

According to the CBO, in 2023, 32 states offered homeowner's insurance to high-risk policyholders through FAIR plans and other residual insurance programs. In 2022, these programs covered 2.3 million properties with an insured value of $837 billion while collecting $5 billion in premiums.

Some of the largest programs and plans can be found in Florida, Louisiana, and California. Florida and Louisiana, both of which are at especially high risk for hurricanes, have state-run insurance programs. These "Citizens" programs offer multi-peril homeowner's insurance policies to state residents who cannot obtain reasonable coverage from private firms. The premium rates charged are higher than prevailing average private rates, though they may be below actuarially fair rates for the given risks. Florida also offers a state reinsurance plan for insurers who experience large hurricane losses; this plan is particularly important to the state's many small insurers. Losses in both Florida and Louisiana trigger special assessments on Citizens policies and, if those are insufficient to cover the losses, on all homeowner policyholders in the state. In the past, Florida has appropriated funds to cover these losses to prevent across-the-board premium increases.

California, which is especially susceptible to wildfires, has a FAIR plan that provides coverage for losses incurred from these events. All admitted insurers in the state participate in the plan and share in profits and losses according to their share of the California market. To be eligible for the plan, homeowners must verify that traditional coverage is not available to them. Their premiums are then based on risk. If total premiums do not cover losses experienced after significant fires, insurers will presumably pass those costs, subject to state limits, onto all California policyholders, in the form of increased premium rates.

The risk of earthquake damage — and its attendant hazards of fires, tsunamis, and so on — is particularly substantial in regions lying along and near various fault lines. These can be found in states like Alaska, Oklahoma, California, Hawaii, Missouri, Nevada, and Texas. Earthquake risk is not covered in standard bundled insurance policies, though insurance covering these events is available from most private insurers in most states, sometimes through FAIR plans. In 2014, across the entire United States, an estimated 7% of homeowners had earthquake insurance.

Again, California falls into the high-risk category for these types of disasters. According to the U.S. Geological Survey, the San Francisco Bay area alone has a 72% probability of being struck by a 6.7-magnitude (or higher) earthquake over the next 30 years. Estimates suggest that a 7.9 quake in the area would cost up to $105 billion.

Before 1994, California state law required firms selling homeowner's insurance to offer earthquake insurance. But after the Northridge earthquake in January of that year caused about $35 billion in insured losses (in 2024 dollars), private companies began to close up their homeowner's insurance businesses. In response, state lawmakers created the California Earthquake Authority (CEA).

This public instrumentality was funded by initial capital contributions from participating insurers, who were then allowed to sell earthquake insurance to homeowners through the CEA free of most regulations (although subject to possible post-event assessments). As of 2024, the CEA had 1 million policies in force, representing about two-thirds of the earthquake policies in the state. Its annual premium revenue was $900 million, and it had $19 billion in reserves.

Owners of property mortgaged through a federally sponsored or guaranteed lender are not required to carry earthquake insurance. This is surprising; after all, the risk exposure exists regardless of whether the losses occur due to the earthquake itself or a related fire or flood. Similarly, there is no federal tie-in mechanism that encourages communities to mitigate earthquake risk — whether that be through building and rehabilitation codes or zoning and strict enforcement of safety measures — as there is for federal flood insurance, which is discussed below.

FEDERAL FLOOD INSURANCE

Historically, private firms offered flood insurance to homeowners. But in the late 1920s, large flood losses along the Mississippi River led most insurers to stop offering this coverage. During the ensuing decades, the federal government regularly engaged in conservation and mitigation activities — particularly through dam construction — to reduce flood damage and provide financial support for losses through one-off disaster-relief funds. Congress also proposed insurance programs during that time, and even passed a short-lived one in 1956. These pushes for federal insurance did not truly bear fruit, however, until the National Flood Insurance Act (NFIA) created the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) in 1968, after New Orleans suffered large losses during Hurricane Betsey.

At the time, many believed the private sector could not insure against flood risk. Flood losses can be extremely large and geographically concentrated, and adverse selection impedes the market. The latter occurs when potential insurance customers have greater knowledge of their risk of being harmed by a given disaster than insurers. When insurers cannot charge premium rates that accurately reflect the true risks of insuring various properties, they tend to charge all customers a uniform, relatively high premium. As a result, only those most at risk purchase the insurance, rendering private insurance unsustainable.

Today, over 22,000 communities participate in the NFIP across 56 states and jurisdictions. Various private companies market, service, and manage claims through paid contracts or NFIP compensation. Participating homeowners may file a claim after a flood regardless of whether the president has declared a disaster.

The NFIP was designed to fulfill two purposes: to offer customers federal flood insurance, thereby transferring property owners' risk of losses to the federal government; and to diminish flood risk through floodplain-management standards, sometimes with support from program funds. These two purposes are tied: Communities voluntarily participate in the NFIP by adopting floodplain standards, and property owners in those communities gain access to federal insurance at a cost, which may be subsidized. An intended by-product of this combination of paid insurance and mitigation incentives is to reduce long-term federal expenditures on disaster assistance.

The tie-in is accomplished through flood-insurance-rate maps. FEMA compiles these maps by conducting studies to identify areas with special flood, mudslide, and erosion hazards; assessing those risks; establishing base flood elevations; and designating insurance zones. The agency updates its maps, with community input, on an irregular schedule — usually when there is significant new development, alterations to flood-protection systems, or environmental changes in a given area.

A key aspect of floodplain-management standards, as noted above, is zoning. Federal regulations restrict development in zones threatened by flood hazards, and require builders in those areas to use certain construction materials and methods that help minimize future flood damage. Builders in zones labeled "special flood hazard areas" (SFHA) — zones with at least a 1% chance of being flooded in any given year — must also elevate the lowest floor of all new residential buildings. The participating community enforces these standards, subject to FEMA review. Studies show, however, that compliance is incomplete.

A community that fails its review may be removed from the NFIP. Conversely, if a community exceeds minimum standards, its residents receive discounts on their flood insurance that increase according to a fixed schedule. In addition, FEMA operates a grant program — funded through NFIP premiums and, more recently, congressionally appropriated funds — to assist participating communities with mitigation planning and activities, particularly for what are classified as "repetitive loss" properties.

According to law, the maximum federal flood-insurance coverage amounts are $250,000 for buildings and $100,000 for contents in low-density housing; $500,000 for buildings in high-density housing; and $500,000 each for the building and contents of businesses and other non-residential properties. These funds do not cover alternative living expenses or business interruption related to flooding, though additional coverage beyond the limits can be purchased in the private market, if available.

If their community participates in the NFIP, property owners in an SFHA are required to purchase flood insurance as a condition of receiving a federally backed mortgage from agencies like the Department of Veterans Affairs, Fannie Mae, and banks regulated by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation. Lenders enforce this requirement, and homeowners may purchase private insurance to meet it. Again, compliance is not complete; studies roughly estimate it to be at about three-fifths of properties in SFHAs. If a community participates in the NFIP but lies outside an SFHA, flood insurance is optional unless otherwise required by a lender.

The NFIA requires that premiums reflect the flood risk of the insured property. There are, however, policies on some older properties whose premiums have been heavily discounted or cross-subsidized as authorized by law; most of these subsidies are now being gradually phased out. In contrast, the community-rating system — whereby premium discounts of up to 45% are granted for properties in communities that effectively reduce flood and erosion risk and protect natural floodplains beyond minimum standards — is intended to be a permanent feature of the NFIP.

In general, premiums for individual properties are now tied to their flood risk, based on the property's unique features; the costs of rebuilding; and recent, more comprehensive data on flood frequencies and sources than those used in flood maps. This differs from past practice, when premiums were solely based on the basic flood-zone category shown on the relevant map. The shift to the new rating system has decreased some premiums but raised many others — some substantially. Flood zones are still used for floodplain-management purposes and the mandatory-purchase requirement.

The NFIA requires the NFIP to be largely self-financing. Today, the program is funded mainly through premiums, fees, and surcharges. Fees include a Reserve Fund assessment, which helps cover future claims and debt expenses related to past disasters. The Reserve Fund is ultimately required to reach 1% of total loss exposures — $13 billion, based on $1.3 trillion in covered properties as of early 2023. The assessment is currently 18% of premiums charged.

According to a 2024 private-sector report, the NFIP has paid out $129 billion (in 2024 dollars) since 1978, including $112 billion for residential buildings, to cover flood losses. Meanwhile, the Congressional Research Service reports that, as of March 2025, total NFIP annual collections from premiums, fees, and surcharges on 4.7 million policies (down from 5.7 million in 2009) was about $4.6 billion. Congress provides annual appropriations to supplement the costs of floodplain mapping; for the 2023 fiscal year, that appropriation was almost $300 million.

The NFIP may borrow up to $30.4 billion from the Treasury to cover its spending. Due to several severe hurricanes that occurred before and during 2017, the NFIP exceeded this borrowing limit, prompting Congress to cancel $16 billion in NFIP debt. The NFIP remains in debt to the Treasury, however, to the tune of $22.5 billion. It services this debt through premiums, although given current premium and surcharge levels and the possibility of future catastrophic-storm losses, studies show that the NFIP is unlikely to fully repay its debt.

Because of the relatively low dollar limits of NFIP coverage and the incomplete enforcement and extent of insurance purchase requirements, there remains a significant coverage gap. According to the CBO, in 2024, about 9% of U.S. properties — or approximately 13 million residential, commercial, government, and other properties — are at high risk of flooding (that is, they have over a 1% probability of experiencing at least one foot of flooding annually). However, only around 8% of these properties had an NFIP policy as of 2023. Nearly two-thirds of high-risk properties were located outside SFHAs; only 4% of those had federal flood insurance. As for high-risk properties located within an SFHA, about 18% had insurance.

In addition to the coverage gap, the NFIP suffers on equity grounds. The program tends to support second homes, vacation properties, and coastal homes of upper-income households rather than the primary homes of lower-income households — including low-income households located away from the coasts.

FEDERAL DISASTER-RELIEF FUNDS

As noted at the outset, not all losses are insured. Some of these uninsured losses are federalized through disaster-relief funds. Though not formally insurance contracts, these funds represent significant federal expenditures on disaster-related assistance that might otherwise be covered under insurance policies, especially for low-income households. They are thus important to take into consideration when discussing federal disaster insurance.

When the president declares a disaster in a designated area, federal disaster-relief funds may be released to affected households; private non-profits; and state, local, and tribal governments that lack adequate insurance, or any insurance at all. These funds are disbursed through the Disaster Relief Fund (DRF), which is administered by FEMA. Other disaster resources are available through the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) and the Small Business Administration (SBA).

DRF funds can be used to clear debris; provide emergency services; fix, replace, and improve damaged infrastructure's resiliency; partially fund home repairs, property replacement, and other household needs; and implement mitigation projects. Some of this money comes from annual appropriations, while the rest comes through supplemental appropriations that Congress passes after large disasters take place.

Most of these funds go to state and local governments through Public Assistance programs, but about a quarter go to households through FEMA's Individuals and Households Program (IHP). The IHP provides financial assistance and direct services to applicants who have no insurance or are underinsured. These disaster-relief funds, which are financed by taxpayers, are redistributive, in part because lack of insurance coverage is closely associated with low income and because of the moral hazard associated with a government program's replacing private coverage.

IHP assistance comes in two tax-free forms: housing assistance for primary residences, and other-needs assistance. In the former, the IHP awards funds for home repair and replacement, subject to a consumer-price-indexed cap (currently $43,600). Funds covering rental assistance, FEMA-provided housing, and short-term lodging expenses are not capped, and can be costly.

Other-needs assistance is subject to a separate consumer-price-indexed cap (currently $43,600). These funds cover displacement assistance; serious need for food and medicine; personal-property repair and replacement; transportation, including vehicle repair and replacement; funeral expenses; child care; moving and storage; cleaning and sanitizing; and, if the applicant lives in an SFHA, three years of flood-insurance premiums. IHP peril coverage implicitly includes the property and contents features of conventional homeowner's insurance, albeit at generally lower levels, but also covers a broader range of loss types; it likely crowds out the purchase of conventional insurance, especially among low-income households. Those residing in an SFHA who receive FEMA assistance, however, must obtain and maintain flood insurance to receive disaster assistance in case of a future flood.

SBA-subsidized long-term loans are also available to households — up to $500,000 for primary homes and $100,000 for personal property lost in a declared disaster. HUD provides Community Development Block Grant Disaster Recovery assistance to state and local governments which, in turn, can disburse these funds to households.

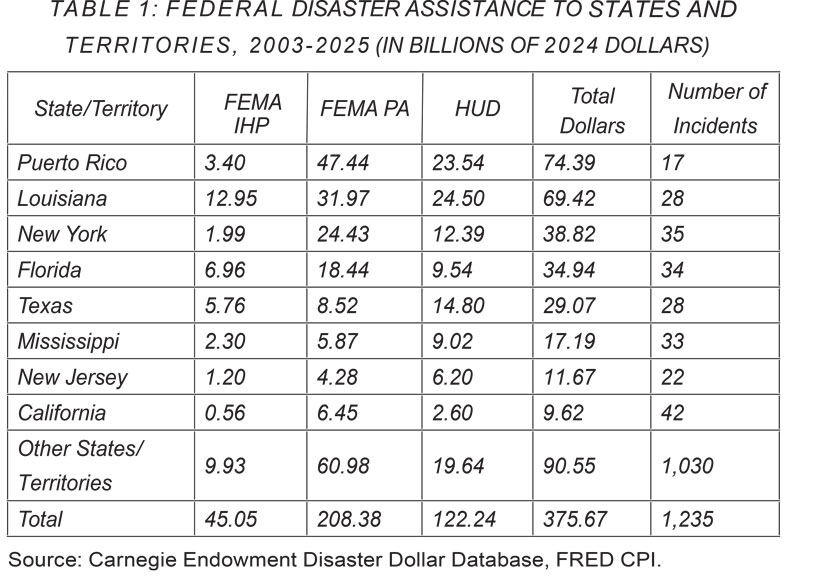

The table below provides a detailed breakdown of federal disaster-relief spending by program from 2003 to 2025; it shows the variable extent of implicit federal-catastrophe insurance, both geographically and in dollar terms.

TERROR RISK

Prior to September 11, 2001, private insurance covered losses to commercial enterprises from acts of terrorism — business interruption, property damage, liability, etc. — at no extra cost. After the attacks triggered large insured losses (estimated at nearly $60 billion in current dollars), terrorism coverage became expensive and was often unavailable. Many expressed concern that this was harming commercial activity, particularly in real-estate development, which was in turn reducing employment rates and hampering economic growth. Insurers also faced a heightened risk of insolvency, in part because some states did not allow insurers to withdraw from any terrorism-risk coverage if they offered standard insurance coverage. In addition, all states at the time required terror risk to be included in workers' compensation coverage.

Expecting private commercial enterprises to mitigate terrorism risk, particularly from foreign sources, is unrealistic. Such is the duty of local, state, and federal governments, who are authorized to gather intelligence, enforce the law and, if necessary, engage in police and military activities to prevent terrorist attacks. It is also difficult for insurers and reinsurers to model the risk of low frequency but potentially high-impact events originating from the malevolence of determined human actors with unknown capacities and targets. As a result, pricing such coverage is challenging. This warrants a federal role in reinsuring some level of terrorism risk.

Congress responded to the September 11th attacks and associated disruption by passing the Terror Risk Insurance Act (TRIA) of 2002, which established the Terror Risk Insurance Program (TRIP). Policymakers designed the program to revitalize the private insurance market and mitigate large private losses caused by the attacks.

Through the TRIP, the federal government shares the losses on commercial property and casualty insurance in the event of a terrorist attack. Most of the federal outlay is recouped from the insurance industry after the fact, depending on the size of the loss. The TRIA requires insurers to make terrorism-risk insurance available, but it does not mandate its purchase or regulate its price beyond what state insurance regulations require.

Although the initial law established a three-year temporary program for acts of foreign terror, Congress has extended the TRIP several times; the program is currently authorized through 2027. Lawmakers and Treasury Department officials have also expanded the program to cover domestic terrorism and cyberattacks, although it largely excludes nuclear, biological, chemical, and radiological attacks. Over successive legislative renewals, and now automatically, the government's prospective share of losses has been gradually reduced, while recoupment amounts have increased.

In order to be eligible for TRIP coverage, three conditions must be met. First, an insurer must suffer at least $5 million in insured losses due to a terrorist attack, as certified by the Treasury secretary in consultation with the U.S. attorney general and the secretary of Homeland Security. Second, for government coverage to begin, the aggregate insured losses from certified acts of terrorism must reach $200 million in a single year. Finally, an individual insurer must meet a deductible of 20% of its annual premiums for the lines of insurance that the TRIA specifies (excluding, for example, crop, group-life, and commercial auto insurance).

Once these thresholds and deductibles are met, the government will cover 80% of each insurer's losses above its deductible, up to a total of $100 billion in aggregate losses. Federal coverage is not available and insurers are not required to provide coverage for any further losses. If the insured losses are less than the aggregate retention amount ($53.366 billion in 2025, set at the annual average of the sum of insurer deductibles for all insurers for the prior three calendar years), the Treasury must recover 140% of government outlays. It would do so by levying surcharges on all TRIA-eligible commercial insurance policies through fiscal year 2029. If insured losses exceed the aggregate retention amount, the secretary is required to recoup a progressively reduced portion of the losses according to a formula in the law, depending on the size and distribution of losses across insurers. He may, at his discretion, recoup more. The secretary also has some discretion regarding how to allocate recoupment.

The TRIP may be viewed as a success. Businesses' take-up rate of terrorism-risk insurance — whether combined with other peril coverages in standard policies or offered as a stand-alone policy — has increased since the passage of the act, from 27% of all policies in 2002 to 77% in 2023, or 58% of policies weighted by premiums collected in 2023. Meanwhile, the program's cost has declined; it now averages about 3% of all premiums paid. Roughly a third of policies are not charged at all.

In total, between 2003 and 2023, insurance companies have collected $56.7 billion in premiums for terrorism-risk coverage. Given that no qualifying terrorism events have occurred over this period, companies have been able to use this revenue to cover other insured catastrophes and pay investors, and to save funds in anticipation of a possible future event. There is also an active terror-risk-insurance market at Lloyd's of London, where insurers are able to obtain reinsurance to buy down their TRIP deductibles and co-pays.

If Congress decides to renew the TRIP in 2027, as it likely will, it should increase the scope of insurer exposure by indexing the minimum size of a terroristic act and the amount of aggregate insured-losses triggers to changes in aggregate industry premiums. It should also raise the deductibles and co-pays to 25%. Congress should further index the current program liability cap to changes in aggregate industry premiums. Otherwise, as the aggregate retention amount gradually rises to the level of the cap, the program and its risk-sharing properties and settling effects will eventually disappear.

THE TRIP AS A MODEL

The current property- and casualty-insurance system for homeowner households is a patchwork. Private insurers provide most coverage, but federal insurance and relief programs and state residual plans also finance significant risks. A patchwork is not necessarily bad if it works, but ours is confusing and complex, and leaves significant gaps and exposures in terms of both types of risks and households covered. Current federal and state insurance and relief programs are also costly to taxpayers, tend to be poorly targeted, and often suffer from severe coverage limits and enforcement issues.

At the same time, the private sector's ability to accurately price insurance policies — especially those covering floods — has greatly improved since the 20th century, thanks to new, more sophisticated modeling techniques and comprehensive data. Catastrophic losses may still require federal reinsurance — with high annual or event-based trigger points and eventual payback, even for large losses — but the current coverage of modest losses through programs like the NFIP and disaster-relief funds, as a technical matter, is largely unnecessary.

Policymakers would do well to replace the federal flood-insurance and disaster-relief funds, along with state residual plans, with an alternative, multi-risk federal reinsurance program modeled on the TRIP. This program should cover all the major risks that households face, including floods, earthquakes, wildfires, hurricanes, tornadoes, high winds, and severe hailstorms. Like the TRIP, it should require companies in a competitive market to offer insurance for these perils but allow them to charge different prices for varied risks. This would make the policies fairer (especially for those in low-risk regions) and incentivize developers to build in less-disaster-prone areas and use safer methods and materials when building in areas of higher risk. The threshold amount in claims or losses that the primary insurer would have to pay before federal reinsurance kicks in should be high, thereby helping federal and state governments save money in the long run.

Additional elements for a program geared toward homeowner households, unlike the terrorism risk program, could include giving direct subsidies to lower-income individuals for insuring their primary residences based on insurance cost and their income levels; mandating that primary properties in high- and moderate-risk areas mortgaged through a federally sponsored or lending program be covered by insurance for all risks; and requiring that participating communities engage in disaster-mitigation activities. Insurance requirements should be rigorously enforced and expanded to ensure adequate coverage, allowing Congress to wind down existing federal relief programs. On net and over time, this will likely result in federal- and state-government savings and, given that relief funding is often exempted from budget spending caps as "emergencies," will reduce the volatility of government expenditures.

For a federal catastrophe-risk reinsurance program for homeowners to work well, policymakers will have to fill in many details. But the TRIP provides a strong foundation for the basic design. The Treasury's Federal Insurance Office, working closely with state regulators and the property- and casualty-insurance industry, should take the lead in addressing the more granular policymaking questions. Like all matters of inevitable catastrophe, it is better to plan now and be prepared than to react after the event.