Presidents and Mass Shootings

Mass shootings occur with depressing regularity in contemporary American life. Whether those shootings take place in Parkland or Las Vegas, Newtown or Fort Hood, the effect on our public discourse is the same. Those on the left call for more gun control. Those on the right talk about mental health and better enforcement of the laws already on the books. The emotional and intellectual responses of most individuals to such tragedies rarely influence our national discourse, except in one notable case: the president of the United States.

Over the course of our history, the role and influence of the president during a local tragedy or crisis have evolved significantly. In the 19th century, presidents had little involvement in crisis response and disaster management, for both technological and constitutional reasons. Their influence was limited technologically because the country lacked the communications capabilities needed to notify the president in a timely manner when disaster struck hundreds of miles away. Even when the telegraph and later the telephone entered the equation, the nation still lacked the mass media needed to provide the American people with real-time awareness of far-flung events. Naturally, this affected the political call for presidents to involve themselves in local crises.

Then there were the constitutional reasons. In the 19th century, there was a bipartisan consensus that responding to domestic disasters was simply not a responsibility of the commander in chief. In the late 1800s, both Democrat Grover Cleveland and Republican Benjamin Harrison made clear that they did not see local disaster response as a federal responsibility. Cleveland vetoed funding appropriated by Congress to relieve drought-stricken Texas farmers in 1887 for this reason. And Harrison told the victims of the Johnstown flood in 1889 that responding to the disaster, which killed more than 2,000 people, was the governor's responsibility.

Unlike past disasters, however, mass shootings are a late-20th-century American phenomenon, with a persistent and frightening increase in regularity in the early-21st century. Current presidents can't look to any of the faces on Mount Rushmore for how to handle mass shootings because those presidents, great as they were, did not have to deal with this challenge. In addition, modern presidents, unlike the presidents of yesteryear, are expected to respond to disasters and to serve as the nation's consoler in chief after national tragedies. But the fact that presidents in our distant past did not have these responsibilities nor face these particular crises does not mean that modern presidents can't learn from the actions of their more immediate predecessors. America has been dealing with this problem for more than half a century now, and the commander in chief can now look to the examples of multiple former presidents. In looking at these examples, perhaps we as a society can begin to discover some badly needed solutions as well.

PRESIDENTIAL SILENCE

The first mass shooting in the collective American memory was the University of Texas at Austin shooting in August 1966. The shooter, armed with six weapons and ensconced at the top of the University of Texas Tower, killed 17 people, wounding more than 30 others. As this was the first high-profile mass shooting in American history, President Lyndon Johnson had no precedents to look to in order to help determine his reaction. It's hard to overestimate the degree to which precedent is a determinant of presidential behavior. Presidents and their staffs continually look to their predecessors to see how similar situations were handled. They often find justification for their behavior in the actions of those who came before them; when they choose to go in a different direction, it is usually not out of ignorance, but in an effort to make some kind of statement about how they believe presidents should act. Furthermore, presidents are acutely aware that journalists and historians track when presidents stick to precedent, and when they break it.

In the case of the University of Texas shooting, though, precedent could not serve Johnson as a guide. Moreover, there were a couple of unique circumstances in that shooting — both related to Johnson's being a native Texan — that would not apply to most future shootings. First, Johnson's Secret Service detail was there in Texas at the time and helped respond to the shooting. While we now have police protocols governing responses to this kind of incident, at the time it was treated as an all-hands-on-deck situation. In addition to local and campus police, individual citizens jumped into action with hunting rifles, and the Secret Service entered the fray as well. The police lacked handheld radios, limiting the ability of responders to communicate with one another. In the end, three brave Austin police officers, along with a deputized Air Force veteran, rushed the tower and silenced the killer, with officers Ramiro Martinez and Houston McCoy firing the fatal shots.

The second unique aspect of the University of Texas incident was that Johnson had a connection to one of the victims. Johnson owned Austin radio station KTBC, or, technically speaking, his wife Lady Bird did. (The radio station would officially become KLBJ in 1973.) On that day in 1966, KTBC reporter Neal Spelce covered the event live and issued an important warning to Austin residents: "Do not go near the U.T. Tower. There is a sniper at the tower, shooting at will...." In those pre-Twitter days, radio was the best way to spread such messages to the widest possible audience. During the harrowing incident, KTBC news director Paul Bolton heard the first list of casualties being read from a local hospital. Bolton grabbed a microphone back in the newsroom. "I think you have my grandson on there," he said, live on the air. "Go over that list of names again, please." Bolton's grandson and namesake, Paul Sonntag, an 18-year-old lifeguard, had come to the campus to pick up a paycheck. He was shot in the head and died instantly. Bolton stayed on the job for the remainder of the incident. Later, President Johnson called Bolton to offer his condolences.

Beyond these two oddities, Johnson's first reaction sounds familiar to 21st-century ears. On August 2, 1966, the day after the shooting, White House press secretary Bill Moyers read a statement by the president that said, "What happened is not without a lesson: that we must press urgently for the legislation now pending in Congress to help prevent the wrong person from obtaining firearms." The statement added that "[t]he bill would not prevent all such tragedies. But it would help reduce the unrestricted sale of firearms to those who cannot be trusted in their use and possession."

A version of the bill Johnson was advocating did pass two years later, after the assassinations of Robert Kennedy and Martin Luther King, Jr. The Gun Control Act of 1968 limited interstate and mail-order purchases of firearms. Johnson signed the bill into law but also argued that it did not go far enough: "The voices that blocked these safeguards were not the voices of an aroused nation. They were the voices of a powerful gun lobby that has prevailed for the moment in an election year."

The Austin shooting would remain the deadliest in the nation's history for 18 years. (In order to abide by a standard definition of "mass shooting," the following addresses those events identified by the Los Angeles Times in a compilation of mass shootings in the U.S. since 1984.) In July 1984, during Ronald Reagan's first term as president, a gunman killed 21 people at a McDonald's in San Ysidro, California. Unlike Johnson, Reagan did not say anything publicly about the shooting. In fact, a search by the New York Times revealed that "[t]he Times did not report any comment from the administration of President Ronald Reagan. His public papers show no statements on the subject in the days following." McDonald's suspended its own commercials following the incident, and in this there appears to be some indication of Reagan's approach to these kinds of matters. When the Tylenol poisonings took place in Chicago in 1982, Reagan had also stood back, letting Johnson & Johnson take the lead in the response. Reagan appears to have been of the view that local tragedies should be handled at the local level, deferring to private-sector entities, when appropriate, to handle problems.

Reagan also appears to have remained quiet after the other two mass shootings during his presidency, one in Oklahoma and one in California. The 1986 Edmond, Oklahoma, shooting appears to be the first one in which a disgruntled post-office employee was the killer, the start of an unfortunate trend of about half a dozen of these shootings that would inspire the phrase "going postal." Similarly, Reagan's successor and former vice president, George H. W. Bush, also generally avoided making statements about the four mass shootings during his administration. A January 1989 shooting at an elementary school in Stockton, California, which took place in the last days of Reagan's tenure, did contribute to a decision early in the Bush administration to issue a ban on the importation of what the New York Times described as "semiautomatic assault rifles."

One shooting in the Bush administration, however, would have an impact on his son's presidential ambitions. In October 1991, a disturbed man crashed his car into a Luby's restaurant in Killeen, Texas, and began shooting. The man appears to have specifically targeted women, killing 15 women and eight men during his rampage. One of the survivors was Suzanna Hupp, later a member of the Texas House of Representatives. Hupp normally carried a .38 revolver with her but had locked the pistol in her car before entering the restaurant in compliance with the law at the time. Without access to her gun, she could do little as the shooter shot her and killed both of her parents. Angered by her helplessness, Hupp pressured state lawmakers to pass a law that would ease the granting of concealed-carry permits for qualified individuals. While Texas governor Ann Richards opposed such a policy and had vetoed similar provisions, new Texas governor George W. Bush — elected in 1994 — signed the bill into law in 1995. A year later, Hupp ran for and won a seat in the Texas legislature.

The bill contributed both to Governor Bush's popularity and to his conservative bona fides; he would be overwhelmingly re-elected in 1998, helping to springboard him to the presidency. To win the GOP nomination, Bush had to overcome skepticism on the right based on his father's reputation as a more moderate Republican. Steps like signing the concealed-carry law, combined with his active cultivation of conservative intellectuals, helped him overcome those doubts.

In an odd coda to the story, President George W. Bush would speak in 2003 at Fort Hood, Texas, where he acknowledged the presence of Hupp. Fort Hood, which is near Killeen, would later witness the terrible 2009 massacre. Many blamed the high number of casualties on a military directive — issued when George H. W. Bush was president — banning weapons on base for most personnel, which superseded the Texas law that Hupp had pressed for and Bush had signed.

WRITING THE PLAYBOOK

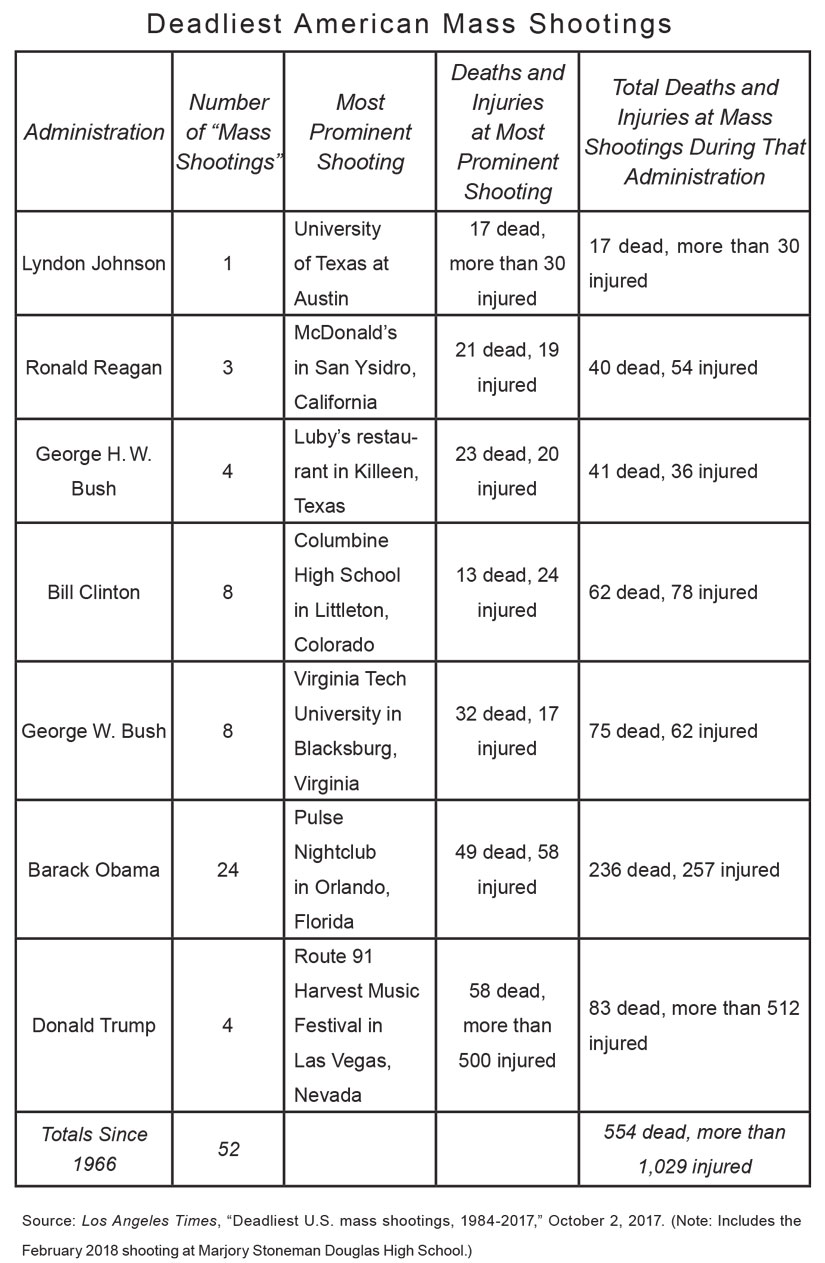

The tradition of presidential silence in the wake of most mass shootings came to an end in the 1990s during the Clinton administration. President Clinton did not weigh in on every one of the eight mass shootings during his tenure, but these events were now frequent enough to warrant presidential attention. Indeed, the alarming fact is that recent presidential administrations have faced an increasing number of mass shootings: eight under Clinton, eight under Bush, and 24 under Obama (see chart below).

In 1993, early in Clinton's tenure, a gunman killed six on a Long Island Rail Road commuter train. This was the incident that inspired the political career of the "Gun Lady," Long Island Democratic congresswoman and gun-control advocate Carolyn McCarthy, who lost her husband in the tragedy. The shooting spree ended when three men — Kevin Blum, Mark McEntee, and Mike O'Conner — jumped the shooter while he was attempting to reload. To acknowledge their heroism, Clinton met with the three men and their families at his Waldorf Astoria suite during a visit to New York. This important symbolic gesture was one of the first uses of this tactic, becoming one of the main pieces of presidential repertoires in the aftermath of mass-shooting events.

Clinton had apparently put some thought into his response. There had been 10 other large-scale shooting events in that year, Clinton's first in office. By meeting with the three men, Clinton hoped to highlight their heroism in the face of depravity, as opposed to having news cycles dwell on the name and background of the murderer. In addition, highlighting those who thwarted the killer, rather than just focusing on those lost in the incident, minimizes the extent to which presidential acknowledgment of the shooting accomplishes the killer's goals. After all, in the killer's sick mind, each victim is a "victory," while spotlighting the heroes who stopped the killer focuses attention on the killer's "defeat." Clinton used the opportunity of the meeting to urge Americans to combat "violence with values."

Unfortunately, the "fight violence with values" approach did not curtail mass shootings — during Clinton's presidency or in any other since. In fact, things got worse in Clinton's second term after a series of school shootings in 1997 and 1998 in Pearl, Mississippi; Paducah, Kentucky; and Jonesboro, Arkansas. The last was perpetrated by two boys aged 11 and 13, who killed five people and injured 10 more at Westside Middle School. The Jonesboro shooting, with its young perpetrators and its setting in Clinton's home state of Arkansas, elicited a more significant presidential reaction, leading Clinton to devote a radio address to the subject in March 1998. This was the first weekly presidential radio address dedicated to the problem of mass shootings.

In the address, Clinton used the phrase that has become so commonplace in reactions to shootings that its use is now derided on Twitter and elsewhere: "Our thoughts and prayers are with the victims, their families and the entire Jonesboro community." Clinton also noted the alarming frequency of the shootings, remarking that "[t]his is the third incident in the last few months involving young children and violence in schools." As a result, Clinton said, he planned "to ask the attorney general to find whatever experts there are in our country on this terrible tragedy to see if there are any common elements in this incident and the other two, and whether it indicates any further action on our part."

Despite the radio address and the directive to the attorney general, Jonesboro soon receded into history as new shootings took place. In June 1998, Clinton visited Thurston High School in Springfield, Oregon, after a shooting in which two children were killed. In his brief remarks, he said he had "instructed the secretary of education and the attorney general to prepare a guidebook to be ready when school opens next year in every school in America, for teachers and parents and for students as well, to describe all the kinds of early warning signals that deeply troubled young people sometimes give."

Even with the steady pace of mass shootings, the public was still understandably shocked by what happened in April 1999 at Columbine High School. On a clear spring day, two Colorado high-school students set out to methodically shoot classmates, murdering 13 and then killing themselves. This event was too big and too horrific for a radio address or a brief visit with some of the survivors in another city. Instead, Clinton went to Colorado the next month, just before the Columbine commencement. While there, he gave what appears to be the first major presidential address in reaction to a mass-shooting event. In front of 2,000 people, and joined by First Lady Hillary Clinton, the president told the moving story of a talented young African-American man from his hometown in Arkansas who had died too young. At the funeral, the young man's father had said, "His mother and I do not understand this, but we believe in a God too kind ever to be cruel, too wise ever to do wrong, so we know we will come to understand it by and by."

During the speech, Clinton made a number of noteworthy points. First, he recognized that these kinds of shootings were becoming a recurring phenomenon: "Your tragedy, though it is unique in its magnitude, is, as you know so well, not an isolated event." He also noted that tragedy potentially brings opportunity, saying, "We know somehow that what happened to you has pierced the soul of America. And it gives you a chance to be heard in a way no one else can be heard." At the same time, Clinton warned of the dangers of hatred: "These dark forces that take over people and make them murder are the extreme manifestation of fear and rage with which every human being has to do combat." Finally, he expanded on his violence/values dichotomy, exhorting the crowd to "give us a culture of values instead of a culture of violence." Clinton closed with the story of jailed South African dissident Nelson Mandela, who managed to overcome hatred and become the leader of his country.

All in all, it was a vintage Clinton performance — feeling the pain of the audience, highlighting the importance of values, and trying to bring the nation together in a shared enterprise. But Clinton was not done with Columbine. Nearly a year after the shooting, he returned to Colorado to participate in a rally for gun control. At the rally, Clinton mentioned both Columbine and other shooting sites: "I don't want any future president to have to go to Columbine, or to Springfield, Oregon, or to Jonesboro, Arkansas, or to all the other places I have been." He also participated in an MSNBC discussion on gun violence to mark the anniversary. In making the pitch for additional gun regulations, Clinton was fitting into the now-established paradigm of Democrats using mass tragedies to call for more gun-control legislation. Republicans, by contrast, argue that additional gun regulations would not work, and instead propose further steps to address mental illness.

Another new development with Columbine was in the follow-up. In contrast to the relatively few presidential reactions to mass shootings in the past, Clinton did not just mention the tragedy in its aftermath and then move on. He referred to Columbine more than 50 times throughout the rest of his presidency. In his final week as president, he devoted the January 13 radio address to school violence, using the word "Columbine" as a kind of synecdoche for the problem of school shootings as a whole. He spoke of the government information hotlines established, again stressed the importance of "values," and touted the need for additional gun restrictions to address the problems. Since the preponderance of mass shootings during the Clinton era happened at schools, his focus was mostly on the problem at the school level. Overall, though, Clinton's reactions to shootings during his administration in general, and to this horrific shooting in particular, established several precedents for presidential responses to mass shootings going forward.

George W. Bush faced the same number of mass shootings Clinton did, though he did not feel the need to remark on every tragic incident. This was his initial response to the March 2005 shooting at Red Lake Indian Reservation in Minnesota. In this incident, a 16-year-old Native American student at Red Lake High School killed nine people before killing himself. Five days after the shooting, Bush spoke about the tragedy in his weekly radio address, noting that he and the first lady were praying for the victims' families. Bush also praised the heroism of Derrick Brun, the unarmed security guard who tried to stop the killer, only to be killed himself. And Bush called for more resources for the tribe, bringing in not only the Departments of Justice and Education, but also the Bureau of Indian Affairs to participate in the response. Still, Bush's five-day delay before responding to the event contrasted with Clinton's immediate reaction to Columbine and highlighted a new vulnerability for presidents in the wake of mass shootings: Non-responses, or even slow responses to tragic events, would leave presidents open to potential criticism.

After the deadliest mass shooting during the Bush administration, there was no question of a delayed reaction. In April 2007, a Virginia Tech University senior slaughtered 32 people on campus before taking his own life. Bush went to the Virginia Tech campus the next day and spoke for about 10 minutes at Cassell Coliseum. In his remarks, Bush noted that it was "impossible to make sense of such violence and suffering." He added, "Those whose lives were taken did nothing to deserve their fate. They were simply in the wrong place at the wrong time. Now they're gone — and they leave behind grieving families, and grieving classmates, and a grieving nation." Other Bush actions included flying flags at half-staff, issuing a proclamation in memory of the victims, and — after reviewing internally what other administrations had done in the aftermath of school shootings — asking key cabinet members to participate in a task force to examine ways to prevent such tragedies from taking place again in the future.

THE OBAMA PROTOCOL

Despite Bush's efforts, mass shootings continued to plague our nation during Barack Obama's presidency. The Obama administration endured 24 mass shootings — more than the three preceding administrations combined. More than any previous administration, Obama and his cabinet appeared to have a playbook for responding to shootings, and they usually commented on or issued statements about them. Gone were the days of ignoring mass shootings and hoping thereby to starve them of attention.

On April 3, 2009, just a few months into the Obama administration, a Vietnamese immigrant killed 13 people at an immigration services center in Binghamton, New York. Obama responded with a standard White House statement: "Our thoughts and prayers go out to the victims, their families and the people of Binghamton." The next mass shooting, however, was more complicated and brought a new element into presidential reactions to mass-shooting events. On November 5, 2009, an Army psychiatrist killed 13 people at Fort Hood, a military base in Texas. The killer was Muslim and was found to have been in contact with the radical al-Qaeda cleric Anwar al-Awlaki, who was later killed by an American drone strike in 2011. The killer's religion, and his ties to an anti-American terrorist agitator, raised questions about whether to classify the shooting spree as a terrorist attack.

Obama's initial reaction, which was included in a speech on Native Americans at the Department of the Interior, did not address the terrorist angle. The president acknowledged that he was going off topic and praised "those who live and serve at Fort Hood. And these are men and women who have made the selfless and courageous decision to risk and at times give their lives to protect the rest of us on a daily basis." He continued, "It's difficult enough when we lose these brave Americans in battles overseas. It is horrifying that they should come under fire at an Army base on American soil."

As more details about the killer and his terrorist ties came out, Obama and his team came under fire for not characterizing the incident as a terrorist attack. In the wake of the shooting, Pentagon officials called for addressing the problem of "workplace violence," which seemed to be a willful effort to avoid the terrorism designation. In addition, the fact that Army leaders had ignored warning signs about the killer's disturbing behavior and increasingly anti-American sentiments raised the question of whether political correctness had deterred the Army from addressing the situation beforehand and preventing the attack.

The Fort Hood shooting also fell into a larger pattern of the Obama administration appearing to try to avoid identifying terrorist attacks as such. A few months before Fort Hood, Homeland Security secretary Janet Napolitano had experimented with the term "man-caused disasters" as a euphemism for acts of terror. She defended the term, explaining that the substitution "demonstrates that we want to move away from the politics of fear toward a policy of being prepared for all risks that can occur." In addition to the deserved mocking of Napolitano's circumlocution, there was a danger to using such a euphemism as well. As the Heritage Foundation's James Carafano explained, "By deliberately trying not to use the T word they run a serious political risk. If something does happen, they'll be accused of taking their eye off the ball and no amount of explanation after the fact will suffice."

In the end, while the use of "man-caused disasters" was mercifully short-lived, the perception that the Obama administration was reluctant to call Islamist-inspired terrorism what it was stuck throughout Obama's entire tenure. In September 2016, he addressed the criticism, calling it a "manufactured" issue, and explaining that "what I have been careful about when I describe these issues is to make sure that we do not lump these murderers into the billion Muslims that exist around the world, including in this country, who are peaceful, who are responsible, who, in this country, are fellow troops and police officers and fire fighters and teachers and neighbors and friends." By that point, there had been three more mass shootings that appeared to have been inspired by radical Islamism, as well as almost 20 more unrelated to terrorism.

POLITICIZED SHOOTINGS

There were so many mass shootings during the Obama years that it would be difficult to analyze all of them in an article of this length. A few of the incidents stand out, however, both because of their magnitude and because of the extent of the presidential reaction. The first was the January 2011 shooting in Tucson, Arizona, that killed six and severely wounded Arizona congresswoman Gabrielle Giffords. This shooting occurred not long after Republicans had taken back the House of Representatives from the Democrats in the 2010 election.

Obama gave short remarks that day about the tragedy. His comments focused on Giffords, as this was one of the rare occasions in which the sitting president had a personal connection to one of the shooting victims. Explaining that Giffords was a "friend," Obama said, "It's not surprising that today Gabby was doing what she always does — listening to the hopes and concerns of her neighbors. That is the essence of what our democracy is all about. That is why this is more than a tragedy for those involved. It is a tragedy for Arizona and a tragedy for our entire country." A few days later at a memorial service in Tucson for the victims, he said, "There is nothing I can say that will fill the sudden hole torn in your hearts. But know this: The hopes of a nation are here tonight. We mourn with you for the fallen. We join you in your grief."

Obama's Tucson speech was moving and not political, but it seemed to mark a change in the national approach. The reaction to the shooting was more politically charged than in the aftermaths of other mass shootings. Giffords had been "targeted" for defeat by Republicans in the previous election cycle, and some on the left suggested that the targeting of specific members for political defeat was in some way encouraging actual targeting for physical harm. The right reacted by debunking this and showing that "targeting" was — and still is — a concept used by both sides. In addition, the killer, despite his shaved head, was not a skinhead or any kind of right-winger, but just a deranged person whose killing spree happened to have hit a congresswoman. This showed the extent to which politicians were just as vulnerable to shooting attacks as the rest of us.

There were several possible causes for the increased politicization of shootings that began with the Tucson attack. One of the top culprits was social media, which led to immediate, and often intemperate, reactions, followed by counter-reactions from the other side. There were only about 17 million Twitter users in 2009, Obama's first year in office; by 2011, there were 118 million. (There are now more than 330 million users.) Reporters and political activists were early adopters of Twitter, making it a more political environment than a representative sample of the population would have created. There was also the fact that a politician had been injured, making the shooter's motivation appear political. And the context, in the wake of a bitterly fought election in which the House changed hands, contributed as well. Finally, there was the fact that mass shootings were becoming an increasingly regular part of American life. Just as everything else in society was becoming politicized, mass shootings were as well.

The next noteworthy shooting was in 2012 at a movie theater in Aurora, Colorado, only about 20 miles from Columbine. The killer, James Holmes, who had dyed his hair to look like the Joker from the Batman comics and movies, entered a midnight viewing of The Dark Knight Rises and proceeded to kill 12 people. Politics entered the picture here as well. ABC News investigative journalist Brian Ross reported that there was a Jim Holmes in Aurora who was a Tea Party member, suggesting that there may have been a right-wing motivation for the attack. The report was inaccurate — Jim Holmes the Tea Partier was not James Holmes the mass murderer — but the incident indicated the degree to which killers' backgrounds were now being scrubbed and analyzed by reporters and others in order to determine their political beliefs and possible motivations. (Since there is at least some evidence that mass shooters engage in their heinous acts in order to gain notoriety, I have intentionally not mentioned any of the murderers' names unless, as in the above incident, it is absolutely necessary for clarity.)

The Aurora shooting transpired during what looked to be a difficult re-election campaign for Obama. His staff notified him about the attack at 5:26 A.M., a rare instance of a president being notified about a mass shooting during what are traditionally sleeping hours. While speaking at a campaign rally in Florida later that day, Obama silenced the crowd in order to address the tragedy: "Such violence, such evil is senseless. It's beyond reason." He also issued a call for unity, remarking how the tragedy "reminds us of all the ways that we are united as one American family." Additionally, Obama ordered flags to be flown at half-staff, and both he and his Republican opponent Mitt Romney agreed to temporarily suspend negative ads in Colorado.

Obama won his re-election battle against Romney, but he would still be plagued by mass shootings. The one that appeared to affect him the most took place shortly after his re-election, when a deranged man killed 26 people, including 20 first graders, before killing himself at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, Connecticut. Obama spoke in Newtown at a vigil for the victims, expressing his frustration with the continuing scourge of mass shootings: "We can't tolerate this anymore. These tragedies must end. And to end them, we must change. We will be told that the causes of such violence are complex, and that is true. No single law — no set of laws can eliminate evil from the world, or prevent every senseless act of violence in our society. But that can't be an excuse for inaction. Surely, we can do better than this." He also appeared to tear up while giving this admittedly difficult talk.

Obama also took a very hands-on approach to comforting the victims' families. According to White House spiritual advisor Josh DuBois's book, The President's Devotional, Obama spent hours with the families. As DuBois put it, "Person after person received an engulfing hug from our commander in chief. He'd say, ‘Tell me about your son....Tell me about your daughter,' and then hold pictures of the lost beloved as their parents described favorite foods, television shows, and the sound of their laughter." Later, toward the end of his presidency, Obama would reflect that "I still consider the day I traveled up to Newtown to meet with parents and address that community as the toughest day of my presidency."

Obama's involvement with victims' families in Newtown was more personal and intimate than in the wake of any other mass shooting. Still, not much changed from a policy perspective. Obama used the tragedy, coupled with the onset of his second term, to make a renewed push for gun-control legislation. There was a sense early on in his second term that this was going to be a galvanizing event for gun-control advocates. The tragedy, however, did not change the basic political dynamics of the gun debate, and the effort failed.

Obama had a personal connection to one of the victims in another shooting, this time in Charleston, South Carolina, where a self-avowed white supremacist slaughtered nine African Americans at the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church. One of the victims was the church's pastor, Reverend Clementa Pinckney. During Obama's eulogy for Pinckney, he noted that, though he did not know Pinckney well, they had been acquainted in their youth, "[b]ack when I didn't have visible gray hair," he joked. After his eulogy, Obama led the church in the singing of "Amazing Grace," a moment that was viewed more than 5 million times on YouTube and that led to many comments about the president's surprisingly good singing voice.

THE QUESTION OF TERRORISM

Two shootings in the final 15 months of the Obama administration would have enormous political implications for both Obama's legacy and the 2016 election to succeed him. Both were carried out by radicalized Muslims and played into the narrative of lone-wolf terrorism rather than the recurrent problem of "workplace violence" or other types of mass shootings.

The attackers at the first shooting, which occurred on December 2, 2015, in San Bernardino, California, were a married Muslim couple; the husband was born in the U.S., and his wife was a Pakistani national. The well-armed and well-prepared pair killed 14 people, mainly coworkers of the husband. The collaborative nature of the attack made it hard to fit into the pattern of seemingly random shootings by deranged loners; it clearly appeared to be an Islamist-inspired terrorist attack. Shortly after the attack, Obama spoke about it on CBS News and downplayed the terror aspect of the shooting: "The one thing we do know is that we have a pattern now of mass shootings in this country that has no parallel anywhere else in the world." By framing the San Bernardino attack as a mass shooting rather than an act of terrorism, Obama gave an opening to then-candidate Donald Trump, who was emerging in a crowded Republican field with his tough rhetoric against Muslim immigration. In contrast to Obama's caution on determining a motive for the shooting, Trump offered a blunt response the day after the attack: "Take a look. I mean, you look at the names, you look at what's happened. You tell me." Later, Trump was even more explicit when he simply said, "I think it was terrorism."

Six months later, as Trump was advancing toward the GOP nomination and a fall matchup against Democratic frontrunner Hillary Clinton, there was another mass shooting with a Muslim perpetrator that roiled the presidential race. In this case, an American-born Muslim, who may have been a closeted homosexual, shot up a gay nightclub in Orlando, Florida, killing 49 people before finally being shot and killed by police. The politics were even more complicated in this case, mixing together gun control, mental instability, Islamist terrorism, homophobic violence, and other hot-button issues into a complex and toxic stew. Candidate Trump entered the fray with a typically controversial tweet: "Appreciate the congrats for being right on radical Islamic terrorism, I don't want congrats, I want toughness & vigilance. We must be smart!" Beginning the tweet with gratitude to supporters who called him right, rather than words of comfort for the victims, was a striking departure from the approaches of past presidents, who typically emphasized their role as comforter in chief. Trump would also later address the issue of LGBT safety in his speech at the Republican National Convention, pledging that he would "do everything in my power to protect our LGBTQ citizens from the violence and oppression of a hateful, foreign ideology [Islamism], believe me."

Obama, for his part, was a little more direct this time, perhaps concerned that tiptoeing around the question of terrorism could hurt Hillary Clinton in her effort to succeed him. Obama travelled to Orlando four days after the attack, along with Vice President Joe Biden, to meet with and comfort survivors and families of the victims. While there, he spoke to the press and acknowledged not only Orlando, but also San Bernardino, as terrorist attacks, saying, "[G]iven the fact that the last two terrorist attacks on our soil — Orlando and San Bernardino — were homegrown, carried out it appears not by external plotters, not by vast networks or sophisticated cells, but by deranged individuals warped by the hateful propaganda that they had seen over the Internet, then we're going to have to do more to prevent these kinds of events from occurring." Despite Obama's new willingness in his final year in office to discuss the reality of lone-wolf Islamist terrorism, Trump won the election at least in part because both Obama and Clinton seemed to search for any possible alternative explanation to avoid acknowledging the Islamist components of these mass shootings.

A LIMITED TOOLKIT

It is far too soon to know if the Trump administration will surpass the Obama administration's tragic record of 24 mass shootings in two terms, but Trump's presidency has already witnessed the worst mass shooting in American history. On October 1, 2017, a 64-year-old man — quite old compared to the profiles of other mass shooters — killed 58 people before killing himself at a country-music festival in Las Vegas. This attack was disturbingly well planned: The killer, armed with multiple weapons, shot his victims from the window of his hotel room and monitored the hallway outside his room via cameras he had placed there earlier. Trump appropriately called the shooting "an act of pure evil" and lavishly praised the bravery of the police who eventually stopped the killer. He also traveled to Las Vegas and met with victims and medical staff at the city's University Medical Center.

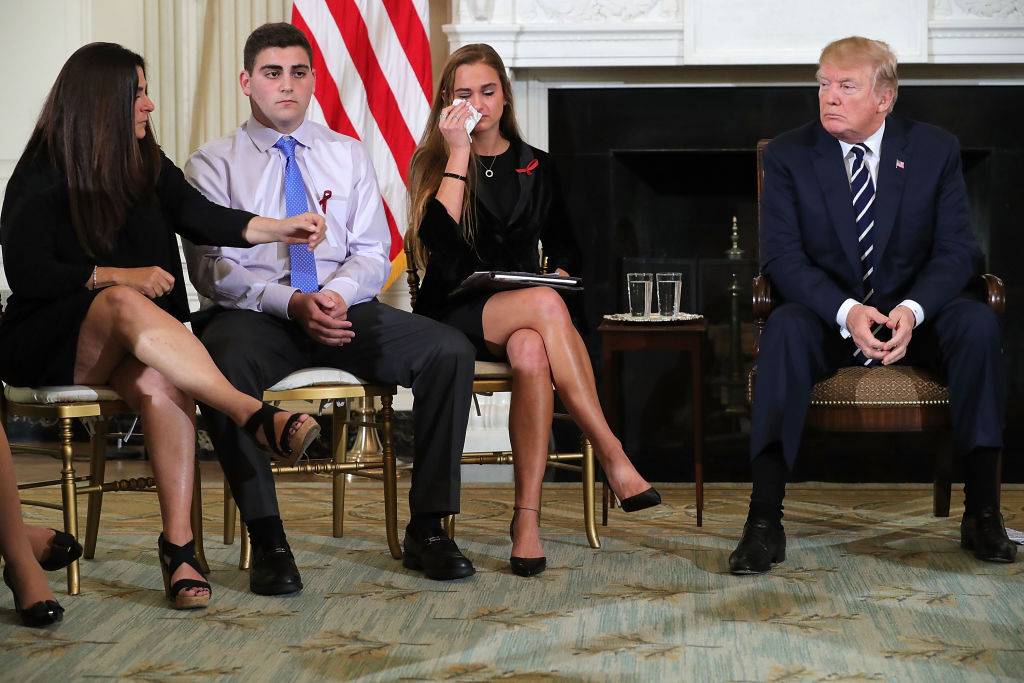

Four months later, an ex-student at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida, killed 17, prompting the students there to rally for new gun measures. This shooting was particularly horrific given details that emerged about the many warning signs that the killer had exhibited. Worried calls to the police and the FBI in advance did little, and even an armed sheriff's deputy on the premises waited outside, failing to engage the killer. In this case, Trump tweeted condolences but otherwise made no public statement on the day of the shooting, prompting USA Today's Ryan Miller to note that "[f]ormer presidents Barack Obama, George W. Bush and Bill Clinton made public comments the same day as mass school shootings during their time in office." Later, Trump held a generally well-reviewed "listening session" with shooting survivors in the White House, and traveled to Florida, where he visited victims at the hospital, as well as the sheriff's office.

We can't yet know how Trump will respond to possible mass shootings for the remainder of his presidency. What we do know is that the binary question of whether presidents should say anything in the aftermath of a mass shooting appears to be no longer applicable. Obama's tendency to give some kind of statement after every shooting, coupled with Trump's tendency to comment on most major developments via Twitter, means that the expectation is now that presidents should react. For a president not to mention a mass shooting would now appear strange and callous.

But even this discussion of whether a president should acknowledge a mass shooting with a statement highlights just how limited the presidential toolkit is for dealing with this disturbing aspect of modern American life. Most presidential reactions to mass shootings have taken the form of rhetoric. Beyond the choice of whether to acknowledge the event, there are also the questions of format, content, and location: Should the president issue a statement, give a press conference, give a major speech, or, increasingly these days, put out a tweet? In terms of content, should the focus be on the victims, the heroism of the first responders, or on potential policy changes the president would like to see carried out? Should the president visit the location? If so, should he attend a memorial service, meet with first responders, comfort the victims, or some combination of all three?

Even with these varied options, the fact remains that no president has been able to get to the heart of the matter and implement, or even offer, compelling policy solutions to the problem. Policy changes at the federal level have been minimal and do not appear to have reduced the potential for these kinds of attacks. At the same time, there has been some progress at the community level, specifically nationwide efforts to secure schools and make them more difficult targets. Schools hold regular drills to prepare for active-shooter situations, install locks and buzzers controlling access, and in some cases allow certain staff to be armed in order to swiftly respond to a threat. There is evidence that some shooters have been deterred from school attacks by these new security measures. Rancho Tehama Elementary School in Corning, California, locked itself down in just 47 seconds in response to a November 2017 threat, thwarting a planned school shooting before it could begin. But efforts such as these, showing progress at the local level, highlight just how difficult it is for the federal government to address the problem. Furthermore, while the number of school-shooting deaths had been relatively low in 2015, 2016, and 2017, the 2018 Parkland tragedy showed that hardening of schools can do only so much to prevent determined and damaged individuals from causing destruction.

Furthermore, even if the number of school shootings had been going down in recent years, the number of mass shootings has not been. Other soft targets such as churches and concerts are also the sites of terrible tragedies, and it is impossible to secure every potential target in a free and modern society. Still, the progress made at hardening schools suggests that, while imperfect, the best solutions to problems at the community level will also be found at the community level. Ultimately, the answers will come from teachers who identify potential threats, parents who are willing to stop and ask questions of potentially dangerous children, police who respond quickly to threats, and brave individuals who are willing to intercede and stop attacks when they can.

Mass shootings reflect some of the deepest challenges confronting our post-modern society: family breakdown, alienation, and the loss of community. Presidents thrust into responding to these situations face problems that cannot be solved by the federal policy levers at their disposal. For all their power and influence, the president's most effective role in the wake of mass shootings is to leave politics aside and act as comforter in chief, speaking for a heartbroken nation. Still, presidents have to be careful in what they say. As Virginia Tech's Robert Denton put it, "You want it to be authentic but not political." Even if a president manages to walk that line in the eyes of his staff, the partisan nature of our society means that not everyone will agree. This hyper-politicization of the populace, coupled with the frequency of shootings, raises a new question for presidents going forward: Can they still credibly serve as comforter in chief as public frustration grows, and America searches for answers to these far-too-frequent tragedies?