The Health-Insurance Solution

America's health-care system suffers from two serious and related problems. First, about 50 million people (of whom about 7 million are undocumented immigrants) are without health insurance. Should they be stricken with serious ailments, they are at risk of having to forgo proper care or incur catastrophic financial losses. Second, the costs of care and of coverage have been growing significantly faster than inflation, wages, and federal revenues for many years — leaving both individuals and the government increasingly unable to keep up. This has meant higher costs for employers (who are the largest providers of health insurance), for families (regardless of how they get coverage), and for the federal government and the states (as spending on Medicare and Medicaid has ballooned).

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act was intended to solve both problems, but now seems unlikely to solve either. In July, the Congressional Budget Office — in its latest projection of the law's effects — concluded that a decade from now, well after the Affordable Care Act is fully implemented, there will still be 30 million uninsured (of whom 8 million will be undocumented). The growth of health-care costs, meanwhile, will have seen no significant slowing.

Many critics of the new health-care law think of it as too radical a reform. But in fact, if the law falls short, it is likely to be because it is not radical enough: It doubles down on some of the worst aspects of our current system instead of seeking a wholly different approach to making health coverage more available, affordable, and efficient. And a wholly different approach is what we need — a different way of thinking about how health care should be organized and financed. The solution we need, to put it simply, is insurance.

The way our insurance system is currently structured encourages inefficiency by reducing the incentives for consumers to assess value. Americans have come to think of health insurance as a means of paying all or part of every health expense they incur. They therefore understand it as necessarily involving broad coverage that includes nearly every medical service imaginable, a low deductible (the amount paid out of pocket before insurance kicks in), and a low co-pay (the amount paid out of pocket after the insurance has kicked in). This understanding of insurance is essentially unique to health care; it is not at all how most other types of insurance — such as auto or home owner's insurance — function. Rather, it is an artifact of our system of third-party payment, in which employers and the government, not beneficiaries, pay for health insurance and care. This has created an environment in which consumers of health care are virtually indifferent to prices.

To improve our health-insurance system, we must first outline the principles by which a more effective system would function. The place to begin is with the concept of real health insurance — that is, a system that offers protection against catastrophic costs while creating a genuine market for less expensive services. This approach could not only get us to universal coverage (albeit limited to protection against catastrophic costs), but also curb the growth of health-care costs that is threatening the nation's fiscal health. Such a model would be an enormous improvement over the current system, and dramatically less expensive: The price tag for its implementation would be about half of the $1.7 trillion that CBO estimates the Affordable Care Act will cost over the next ten years.

OUR STRANGE INSURANCE SYSTEM

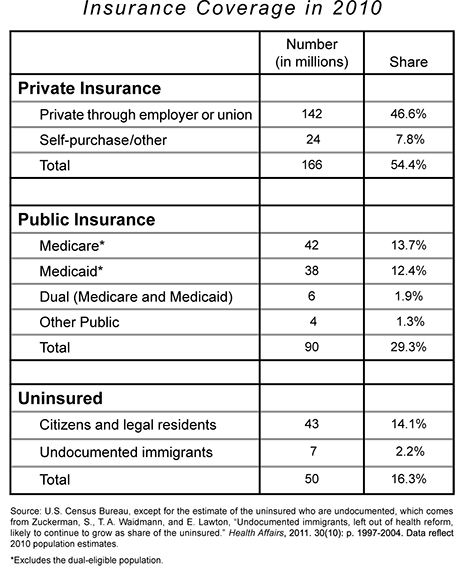

Of the 306 million residents of the United States in 2010, about 256 million had some form of health insurance. Of these, 166 million were covered by private insurance (either provided by employers or purchased in the individual market) and 90 million were covered by some form of public insurance (primarily Medicare and Medicaid). The remaining 50 million were uninsured.

The way in which those Americans who have insurance coverage receive and use it explains a lot about why health-care costs are so high, and why so many people are uninsured. Consumers of health care, like consumers of any other product or service, spend most wisely when they spend their own money and have the information they need to make judicious decisions. Perhaps the strongest evidence for this point comes from the RAND Corporation's Health Insurance Experiment, which ran from the early 1970s through the early '80s, randomly assigning families to health-insurance plans of varying design. One of the main findings of this experiment was that families with the least generous plans (those who had to pay a full 95% of their costs out of pocket, up to a cap) spent nearly 30% less on medical care — with little or no difference in their health.

To be fair, the RAND experiment ended almost 30 years ago, and more recent data indicate that more generous coverage of certain goods and services — particularly drugs — can improve patients' health outcomes. But the point remains that insurance with broad coverage, low deductibles, and low co-pays not only results in high premiums: It also encourages excessive use of health-care services, inevitably leading to wasteful spending. Nevertheless, this is precisely the sort of coverage that prevails in our current system of private insurance.

Americans have never had as much of their health-care spending covered by insurance as they do today. In 1965, more than 50% of health-care spending was out of pocket. Now, the average is closer to 13%. As a result, consumers of health-care goods and services do not perceive that they are spending their own money; they thus have no real sense of what procedures, drugs, and devices cost, or of how different options compare in terms of either price or quality. This is a recipe for inefficiency and rising costs. And these growing costs, in turn, leave more and more people unable to afford insurance.

The way many Americans obtain insurance also contributes to the peculiar incentives that shape our system. About 142 million of those who are insured in the private insurance system receive coverage through their employers (or through their spouses' or parents' employers). This makes health coverage quite unusual among consumer products. As a general rule, our employers don't buy things for us; instead, they give us cash income, and we buy what we choose. The reason health insurance is different is federal policy: Since the 1950s, money that an employer spends on an employee's health insurance has been excluded from the employee's taxable income (despite the indisputable fact that employer-provided health insurance is income). This exclusion has resulted in a massive tax subsidy that increases with the generosity of the coverage.

The tax exclusion for employer-provided coverage creates a huge incentive for workers to take part of their salaries in the form of health insurance rather than of cash. This is particularly true of higher-income workers whose marginal tax rates are higher. And the tax exclusion comes at an enormous cost to the government. According to the Office of Management and Budget, the exclusion reduced federal tax revenue by about $284 billion in 2011, of which about $170 billion (60%) took the form of reduced income-tax payments and $114 billion (40%) took the form of reduced payroll-tax payments.

And the exclusion is not the only tax subsidy for coverage. For example, people who are self-employed can deduct the cost of health insurance from their taxable incomes. This deduction is designed to level the playing field somewhat for self-employed people who purchase their insurance on the individual market. The cost to the government of this subsidy for the self-employed (approximately $10 billion in 2011) is relatively small compared to the exclusion for employer-provided coverage. Health care is further subsidized by allowing people who purchase care out of pocket to deduct all health-care expenditures that exceed 7.5% of income. This results in another $5 billion to $10 billion in lost revenues each year, bringing the total cost of tax subsidies for health care to more than $300 billion a year.

These subsidies are not only very costly to the taxpayer, but also blatantly unfair to the millions of people who purchase insurance on the individual market but do not qualify as being self-employed (and therefore receive no tax benefit). They are also often unfair to people who are self-employed: Because insurance-premium tax deductions apply only to income earned in the year of the deduction — and because self-employed people can easily have no income to report in a bad year — they stand to lose their tax subsidies for insurance precisely when they need them most. Moreover, people who do not receive generous tax subsidies have to finance their insurance or their health care with after-tax dollars — a significant financial burden. Not surprisingly, there is virtual unanimity among economists that the tax exclusion and the other tax subsidies are bad public policy, and that they are an important part of the reason for the inefficiency of our health-care system and for the high number of uninsured.

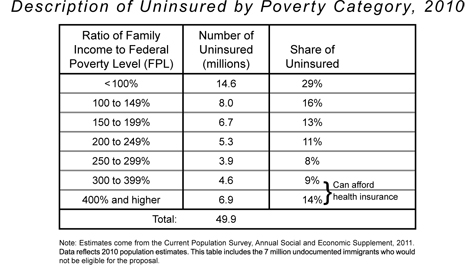

Not all of those who are uninsured lack coverage because they cannot afford it, however. There is no universally agreed-upon measure of when a family can afford insurance, but the standard proposed by health economists Kate Bundorf and Mark Pauly a decade ago offers a reasonable guide. Generally speaking, they deem insurance to be affordable if a family earns more than 300% of the federal poverty level, or about $70,000 per year for a family of four.

Using this criterion — as shown in the table below — about 11.5 million of the 50 million uninsured in 2010 were in households that could afford to purchase health insurance or cover routine out-of-pocket expenses for health care. Thus 38.4 million residents would have needed financial support to purchase insurance or to pay directly for their health care. Of this group, about 7 million were undocumented, leaving 31.4 million legal residents who were uninsured because they could not afford coverage.

The two faces of our health-care crisis — the growing cost of coverage and care and the growing number of uninsured — are, as we have seen, closely related, and even champions of the Affordable Care Act have to admit that both remain grave problems after the law's enactment. Although the law is sometimes described as "pursuing universal coverage," the Congressional Budget Office estimates that it will leave 30 million Americans uninsured a decade from now. And though the law was often sold on the notion that it would "bend the cost curve" downward, many who have studied the plan do not expect that to happen. CBO director Douglas Elmendorf put the point rather tactfully a few months after the law's enactment, noting that "rising health costs will put tremendous pressure on the federal budget during the next few decades and beyond. In CBO's judgment, the health legislation enacted earlier this year does not substantially diminish that pressure." To the extent that there are real attempts to reduce costs in the Affordable Care Act, they are almost entirely in Medicare (where tighter price controls on providers would be imposed), not in the private system.

As for the private system, the law tries to make it possible for more people to obtain the same form of health insurance that is now causing so many problems for American health care. A better approach is needed — and it should be built around a better form of health insurance.

THE ALTERNATIVE

Most Americans believe that insuring people who cannot afford health-care coverage — assuming it can be done cost effectively without reducing the quality of care — is a proper goal of public policy. Such a goal can indeed be responsibly pursued, if we conceive of it in terms of real insurance. We should aim, in other words, to make catastrophic coverage available to everyone.

Outside of health care, there are almost no forms of insurance that cover small and routine expenses. Auto insurance does not pay for oil changes. Home owner's insurance does not pay for house painting. Rather, both of these forms of insurance protect their beneficiaries from only serious or catastrophic financial losses — from costs involved in, say, a serious car accident or a devastating house fire. If otherwise unaffordable health expenses were covered by insurance, and routine health expenses were treated like normal household expenditures, the entire population would be shielded from devastating losses while an efficient consumer market in health care could emerge.

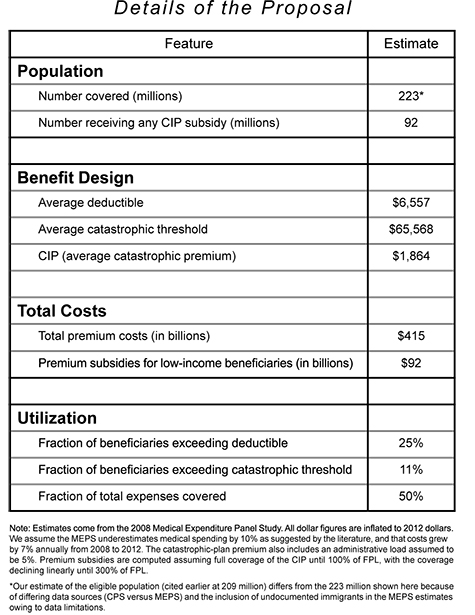

A sensible and affordable health-insurance system would thus be based on universal catastrophic coverage. The federal government could actually provide it to every one of the 209 million Americans who are not already covered by public insurance, and at a cost far lower than that of the Affordable Care Act.

Catastrophic insurance involves nothing more than a high-deductible policy that covers all, or nearly all, health-care expenses in excess of the deductible amount. For today's uninsured Americans, such coverage would offer vital protections they do not now have. For those who are now insured, it would displace the catastrophic portion of their existing insurance policies — whether employer-provided or individually purchased — thereby reducing the costs of those plans.

To be sure, a high-deductible plan could leave some people with higher out-of-pocket costs than they would like or think they can afford. But nothing in this proposal would preclude employers from providing insurance to supplement the catastrophic-coverage plan supplied by the government. Nor would any individual be prohibited from purchasing supplemental insurance in the private market. The key, however, is that the premiums for such supplemental coverage would no longer receive the tax subsidies provided in our current system. Everyone in the private market, regardless of his circumstances, would receive the same benefit and the same catastrophic coverage. Beyond that, the market would be left to work.

It is impossible to lay out every detail of such a proposal here, but a basic outline is not difficult to sketch. It would involve a publicly funded universal catastrophic-coverage benefit, largely funded by a dedicated per-capita tax. Since the new benefit would reduce each beneficiary's current insurance costs by a like amount, the vast majority of beneficiaries could pay the full amount of the tax out of these savings. Those who are needy would receive subsidies (from a series of revenue sources and savings described below).

Each year, all legal residents not covered by Medicare or Medicaid would receive identical high-deductible health-insurance policies from a private insurer contracted by the federal government. A beneficiary's high-deductible policy would be automatically renewed annually until he became eligible for Medicare, or unless he became sufficiently needy to qualify for Medicaid.

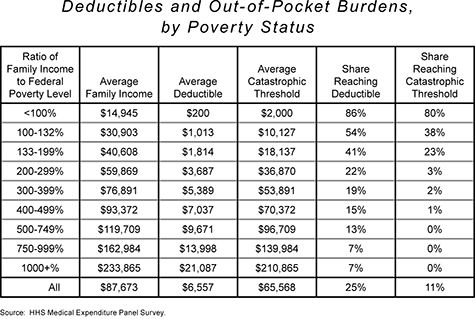

The deductible for each individual's policy would be means-tested. We propose to set the deductible at 10% of the "surplus" income (defined below) earned by an individual's family in the prior year. Each member of a family would have his own deductible, but the total exposure of any family would be capped at twice the individual deductible.

Surplus income would be defined as the amount of adjusted gross income in excess of the income below which a person or family qualifies for Medicaid. To illustrate: If a family of four had an income of $63,000 (including the value of any employer-provided health insurance), and the state Medicaid income threshold was $23,000, surplus income would be $40,000. At this level of income, the deductible would be $4,000 for a single member of the family (10% of surplus income and a little more than 6% of total income), with a deductible cap of $8,000 for the entire family. If the household's income was $28,000, the deductible per family member would be 10% of the $5,000 of surplus income, or $500, which would be less than 2% of total income. And if household income totaled $123,000, the deductible per family member would be 10% of $100,000, or $10,000, which would be just over 8% of total income.

To smooth out large fluctuations in income, the deductible could, where appropriate, be computed using the average of two or three years of income instead of only the prior year's earnings. It might also be wise to include a wealth test similar to the one now used for Medicaid qualification, taking account of assets and recent wealth transfers. This would ensure that people who have modest incomes, but are nevertheless wealthy enough to cover all or part of their health care, are not able to game the system. Neither type of means test should be difficult to implement, as both are already used for other federal entitlements.

Such a system of health insurance — catastrophic coverage without today's tax subsidies that distort the incentives to buy health insurance and consume health care — would encourage consumers to attend to cost and value in their routine health spending. And to ensure some incentive to seek less expensive care beyond those routine purchases, we propose a 5% co-payment after the deductible has been met, payable on health expenses incurred between the deductible and a "catastrophic threshold," which we would set at ten times the deductible. For example, a person with a $4,000 deductible who reaches his catastrophic threshold of $40,000 would increase his out-of-pocket spending by a maximum of $1,800 (5% of the difference between $40,000 and $4,000). Such cost-sharing would reduce the burden of this proposal on the federal budget while also making consumers of care more price conscious — thereby driving further savings.

For certain preventive care and exceptionally high-value treatments that can be shown to save money — like prenatal care, statin drugs to avert heart attacks, and some drug and treatment regimens for chronic illnesses — policymakers could carve out exceptions. These treatments would be fully covered without lowering the deductible, thus reducing the likelihood that this reform would result in patients' avoiding necessary care in order to save money. And for people with persistently high medical expenses driven by chronic illnesses (which could cause these patients' deductibles to be completely used up each year without covering routine or "maintenance" medical expenses), the system proposed here could include an administrative process by which they could apply to lower their deductibles.

The next table shows the deductible and catastrophic-threshold amounts in relation to the federal poverty level. Holding family size constant, the benefit becomes increasingly generous as income falls — i.e., the deductible and the catastrophic threshold fall as income declines. In addition (as noted in the final two columns), because the deductible and the catastrophic threshold both rise with income, people with lower incomes would, appropriately, receive far greater benefits from this reform than would wealthier Americans.

For the purpose of this conceptual exercise, we do not propose any modifications to the existing public-insurance programs (Medicare and Medicaid). Nor do we propose any changes in the "safety net" of emergency care, whereby uninsured patients are treated by hospitals even if those patients cannot afford to pay the bills. (We do expect, however, that a reform like this one would reduce the use of emergency care, and thus partially level the playing field for hospitals relative to other health-care providers.) Our focus is instead the private insurance system in which people below the age of 65 and above the threshold for Medicaid benefits purchase their health care.

The basic idea of a reform like this one is to create a functional health-care market for so-called "maintenance" care — physical exams, occasional doctor's visits for minor injuries and sicknesses — while offering comprehensive protection against the extraordinary costs of catastrophic care. In order to maximize the efficiency of this market, health-care consumers must have sufficient information to make informed purchasing decisions — information they currently do not have. We thus propose that this plan include a provision for the development of an online database containing pricing and quality ratings of all health-care providers and health-care goods and services. This would enable consumers to make better-informed purchasing decisions. Reformers who believe that market principles can work in health care must acknowledge that transforming today's system into a genuine market will require serious efforts to make information available to consumers.

COSTS AND SOURCES OF FUNDING

Using available evidence about risks and costs — as well as the example of existing catastrophic-coverage plans — our preliminary estimate of what high-deductible insurance would cost, on average, is about $2,000 per person per year (an average of $7,200 per family). The aggregate cost to the federal government of providing this type of coverage for the entire eligible population would thus be roughly $420 billion per year.

This is obviously a great sum of money. But about $328 billion (78%) of this amount could come from people who are currently insured or can afford it, without a reduction in their disposable income (as described below). As for the balance, recall that the federal government already spends more than $300 billion a year through the tax code to subsidize today's misguided insurance system. Recall too that, within that system, Americans pay a great deal more still to secure their coverage (including catastrophic coverage). Thus, by effectively replacing our current insurance system with universal catastrophic coverage and a consumer market in supplemental coverage and in care for more routine expenses, the money we spend on health care today would, in essence, be redirected.

To see how, it is worth examining the situations of the three categories of people who would be affected by this reform: those currently covered by employer-sponsored insurance, those who purchase insurance in the individual market, and those who do not have insurance and effectively self-insure. It is important to note that in all three cases, health insurance and health care are paid for by beneficiaries — either directly (out of pocket) or indirectly through employers who provide insurance in lieu of higher wages.

On average, each person who receives a high-deductible insurance policy would have an economic benefit with a market value of $2,000. In the case of a person with employer-provided insurance, the plan we propose would result in his employer's spending about $2,000 less on insurance for each member of his household. Because of the way the labor market functions, these savings would accrue directly to workers.

The value of services provided by a worker is determined by the marketplace. For a worker who receives health insurance from his employer, that value is roughly equal to the employee's cash income plus the value of any insurance or other fringe benefits received. For example, if a head of household has a salary of $50,000 and a typical employer-sponsored, full-coverage health-insurance policy worth $13,000 (for an average-sized family), that person's services have a market value of $63,000. If for any reason his employer was relieved of all or part of the cost of the insurance, that employer would thus be induced by the market to increase the worker's compensation by the amount he had previously paid for the insurance. In this way, as extensive empirical evidence has demonstrated over the years, the savings in insurance costs would be passed on to the employee. As a result, the employee would end up with both a catastrophic insurance policy and increased cash compensation of equal value. This increase in cash compensation would allow the government to tax these individuals up to a like amount to pay for the new benefit without reducing their disposable income.

In the case of people who purchase insurance in the individual market, disposable income would increase by the amount the self-purchaser had been paying for the catastrophic-coverage component of his health insurance. And for those who self-insure (i.e., pay out of pocket for their health care), the increase in disposable income would come from the elimination of any current or future cash outlays necessary to cover health-care expenses that exceeded the deductible.

In this way, most of the cost of catastrophic insurance for the 166 million people who are now privately insured (either through employers or through direct purchases on the individual market) and for the 11.5 million uninsured who can afford insurance — a total of 177.5 million people, less any currently insured undocumented immigrants — could be paid for largely by these same people with little or no reduction in their disposable income. We propose that this be achieved through a per-capita tax called a "Catastrophic Insurance Premium," or CIP. The CIP tax would be set to roughly equal the actuarial value of the benefits provided. As suggested above, we estimate that the CIP would be around $2,000 per person for people whose incomes are above 300% of the federal poverty level, while those below that level would pay a lower tax based on a sliding scale (declining to zero for all people below the poverty level).

Those lower (but still significant) means-tested payments would cover part of the aggregate amount of the CIP for the uninsured group. But it is not possible to subsidize the uninsured poor without also subsidizing the insured who are in similar economic circumstances. (This is necessary not only on grounds of fairness, but also because if subsidies were available only to the uninsured, insured people would drop their insurance to be able to take advantage of government support.) We thus propose that for anyone with an income below 300% of the federal poverty level, regardless of insurance status, the CIP be subsidized to some extent. The amount would be computed assuming full subsidization of the CIP until 100% of the poverty level, with the subsidy declining linearly until 300% of the poverty level.

As shown in the table, under these assumptions, the cost of subsidies for the uninsured — combined with the subsidies for the insured, less revenue from co-pays — would total $92 billion. This is the amount that would have to be raised beyond the CIP tax in order to provide a catastrophic policy for the 209 million in the eligible population.

SOURCES OF FUNDING FOR THE NEEDY

That $92 billion funding shortfall required to subsidize the needy (about 22% of the $420 billion requirement) could be funded in a number of ways made possible by this reform.

To begin with, today's various tax exclusions for health coverage would be eliminated, resulting in additional government revenue that could be directed to cover this shortfall. As noted earlier, the direct cost of the tax subsidies is more than $300 billion and growing. About $180 billion of that amount consists of income-tax revenue lost to the Treasury, which increases the annual deficit by the same amount. Another $120 billion is revenue lost to the Social Security and Medicare systems, which adds to the already huge unfunded liabilities of these programs. Because this proposal would provide catastrophic coverage for all, and therefore cause employers to stop providing such coverage, the amount of money excluded from taxation — and, accordingly, the taxes lost — would decline even if the exclusion were not eliminated.

Specifically, the amount of income taxes lost would fall by about 45%, which would reduce the revenue loss by roughly $80 billion. That would leave about $100 billion in tax subsidies, which would be equivalent to the amount lost to the Treasury today by excluding from taxation what employers currently spend on the non-catastrophic portions of insurance coverage. The Treasury would therefore take in an additional $100 billion in revenue as a result of eliminating the tax exclusion. That by itself would be more than enough to fund the entire $92 billion shortfall.

As we have seen, the tax subsidies are expensive and inequitable, and they distort our health-care system. But they are also popular, and eliminating them would be no simple matter. There are, however, ways to make the elimination of subsidies to workers who get their insurance through employers more politically palatable. Perhaps the most obvious is to phase out the subsidies over time — ten years, say. But a much more powerful way to make the elimination of the tax subsidies acceptable to voters would be to phase in an offsetting general tax cut of a like amount. And we believe that such a cut could be paid for through systemic cost reductions resulting from this proposed reform plan.

After all, total government spending would certainly decline as a result of this proposal. One can only imagine how much this reform would change the economics of health care: For example, universal catastrophic insurance coverage would obviate the need for virtually all of the current, highly complex federal and state laws and regulations designed to administer and police such things as coverage of pre-existing conditions ("guaranteed issue"); mandated coverage of specific health conditions; one-size-fits-all pricing ("community rating"), which requires insurance companies to sell insurance for the same price to everyone regardless of health status; portability of insurance policies when changing jobs; regulations on policy cancellations; the Affordable Care Act's mandate to purchase insurance (and a system of "taxes" on those who don't comply); management of "insurance exchanges"; and the bureaucracy necessary to administer such a complex system and to police the fraud that must inevitably ensue. Almost all of the costs of these regulations, as well as the negative cost effects of the intrusions into the market that accompany them, would disappear if this plan were in place. Also gone (or much diminished) would be the 50 state insurance commissions and the regulatory bureaucracies over which they preside.

To be sure, there would be offsetting costs needed to administer the new system, but we believe these costs would be much lower than the likely savings. An estimate of the net savings in government expenditures resulting from the elimination of these regulations and bureaucracies is beyond the scope of this essay, but it promises to be significant — perhaps enough to fully pay for the incremental costs of the reform by itself.

It is also important to see how a reform like the one proposed here would tend to decrease health costs overall, not just those borne by government. As noted above, today's health-care system induces significant over-consumption of both insurance and care by making the consumer relatively indifferent to prices. This reduces normal market pressures on prices, and in turn drives cost increases.

Moving to the system proposed here would counteract this tendency by giving people an incentive to buy care directly, rather than to buy insurance in order to cover minor expenses. Using insurance to cover "maintenance" expenses is unduly costly because it is inefficient and cumbersome: In paying for these types of expenses, insurers act as needless middle men. The insured patient pays premiums to the insurance company, which collects the money, processes paperwork, and pays the health-care provider with the money supplied by the insured. Were patients to pay for "maintenance" care directly, they could thus avoid unnecessary cost and hassle. If the risk of catastrophic losses were covered and today's tax subsidies were eliminated, then, it is likely that many people would choose over time to self-insure.

Were more Americans to pay for health-care costs directly and thereby become more value conscious, the resulting reductions in spending would free up disposable income for other purposes. Excluding Medicare and Medicaid, personal health-care spending now totals about $1.8 trillion per year. Thus even a 5% reduction in health-care outlays would save consumers of health care $90 billion per year. This would increase the disposable income of health-care consumers and thus also provide a further source of funding to secure coverage for the needy.

Financing this proposed reform would require government spending, to be sure, but it would still cost substantially less than current estimates of the cost of the Affordable Care Act. At the same time, it would make available significant resources that are currently sustaining the inefficiencies that plague our system today.

REAL INSURANCE

The approach to health insurance described here would have several important advantages over both the health-care system we have long had in America and the reforms sought by the Affordable Care Act. This proposal would eliminate the risk of catastrophic financial loss as a result of health crises for all citizens and legal residents. The recent health-care reform law, meanwhile, would leave well over 20 million citizens and legal residents uninsured. The incremental annual funding needed for this proposal — about $92 billion — would be significantly less than the projected cost of the Affordable Care Act's coverage provisions, and could be largely or entirely paid for by the savings made possible by the proposal itself.

The implementation of this proposal would make the regulation of health insurance substantially simpler and, in turn, would reduce government spending. The direct savings from this simplification could be used to fund all or a portion of the new system. It would also eliminate many of today's incentives to over-consume health care by turning passive recipients of health care into more value-conscious consumers. And the elimination of the tax exclusion and other tax subsidies would remove a great inequity in the tax system that has existed for almost 60 years.

To be sure, what is laid out here is only a sketch. Further details of design, implementation, and transition, as well as more refined cost estimates, would have to be worked out before such an idea could become a full legislative proposal. But the purpose of this sketch is to suggest a conceptual approach to health insurance that could make the system more efficient and, at the same time, also provide real insurance coverage for all Americans at a reasonable cost. Pursuing universal catastrophic health insurance would allow us to overcome many of the obstacles that have stood in the way of a rational health-care system for decades. And it could offer a market-friendly and practical path to universal coverage — without breaking the bank.