The Disappearing Conservative Professor

When concerns over the homogeneity of university faculty are raised, conservatives and liberals tend to hunker down into a battle of grievances. Conservatives point to instances of political bias and the need for "real" diversity in higher education, while liberals remind their conservative opponents of the still-low number of minority professors and the importance of their perspectives. It should be possible to overcome this impasse. Both the right and left tend to define diversity too narrowly and inconsistently, and both would benefit from broadening their appreciation for the value of diversity in higher education.

But while such a transformation in understanding would be helpful, it will not immediately solve a more pressing and formidable challenge: the lack of conservative professors in American universities. This problem is pressing because conservative professors have become increasingly scarce in recent decades even as the share of minority faculty has increased; it is formidable because the obstacles to increasing political or ideological diversity are greater than those that impede other diversification efforts.

THE SHRINKING CONSERVATIVE PROFESSORIATE

By most accounts, 1969 was not a banner year for conservatism, at least not on America's college campuses. Looking back, however, it is striking just how well represented conservatives were in the ranks of the American professoriate. In that turbulent year, about one in four professors were at least moderately conservative, according to survey data collected by the Carnegie Commission on Higher Education.

That substantial minority of conservative voices on college campuses began to diminish sharply in the late 1980s and early 1990s. When the Carnegie Foundation conducted its faculty survey in 1999, it found that a mere 12% of professors were conservatives, down from 27% in 1969. Using a different dataset from the Higher Education Research Institute, political scientist Samuel Abrams discovered a similar decline. Overall, Abrams estimated that the ratio of liberal to conservative professors has increased by about 350% since 1984, even though there was no equivalent change among the American public or college students. As a consequence, very few of today's college presidents can claim that one in four of their faculty members are conservatives.

These vanishing conservative thinkers have not been replaced by moderate ones. Since the late 1960s, self-identified liberal professors have become increasingly common on college campuses. In fact, according to Abrams, most of the growth in liberal faculty in recent decades "came at the expense of the moderate identifiers who are now identifying as liberal."

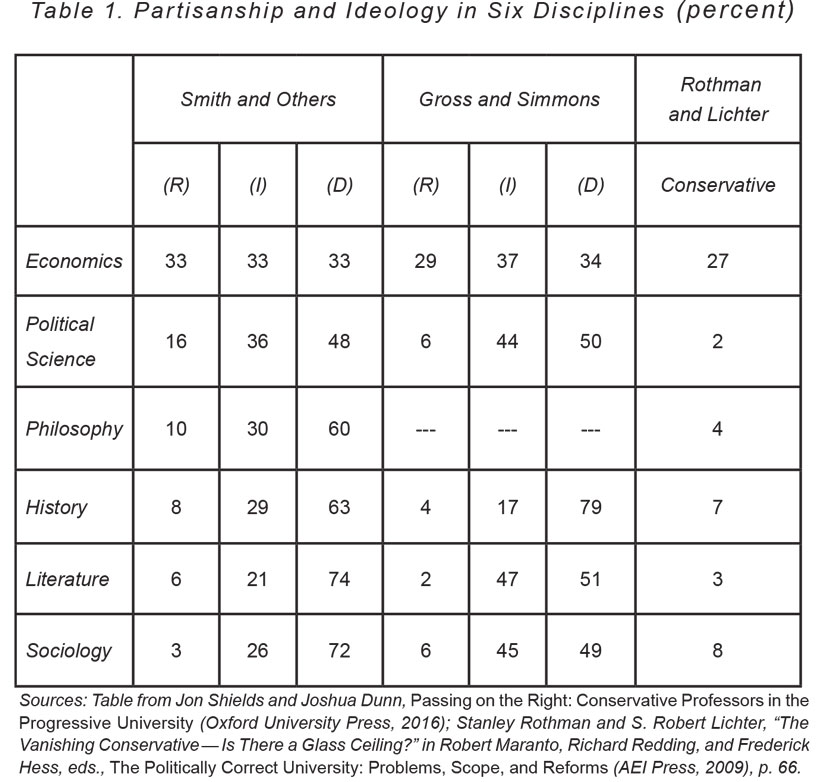

Conservative representation is even worse today in the social sciences and humanities, where they have practically disappeared from many areas of inquiry. Nearly every recent survey of the university places the percentage of conservative and Republican professors in these fields in the single digits. Conservatives also tend to cluster in economics departments, leaving other disciplines with hardly any center-right thinkers. As shown in Table 1 below, by some prominent measures Republicans make up 4% of historians, 3% of sociologists, and a mere 2% of literature professors.

And because conservatives tend to cluster in certain kinds of institutions — especially religious and military colleges, as well as those located outside of New England — many of America's best colleges and universities have become one-party campuses. This problem is especially acute on the campuses of elite liberal-arts colleges. According to a recent study on faculty party affiliation by the National Association of Scholars, the ratio of Democrats to Republicans at Williams College is 132:1; at Swarthmore it is 120:1; and at Bryn Mawr it is 72:0. At many of America's best research universities, the ratios are only moderately better.

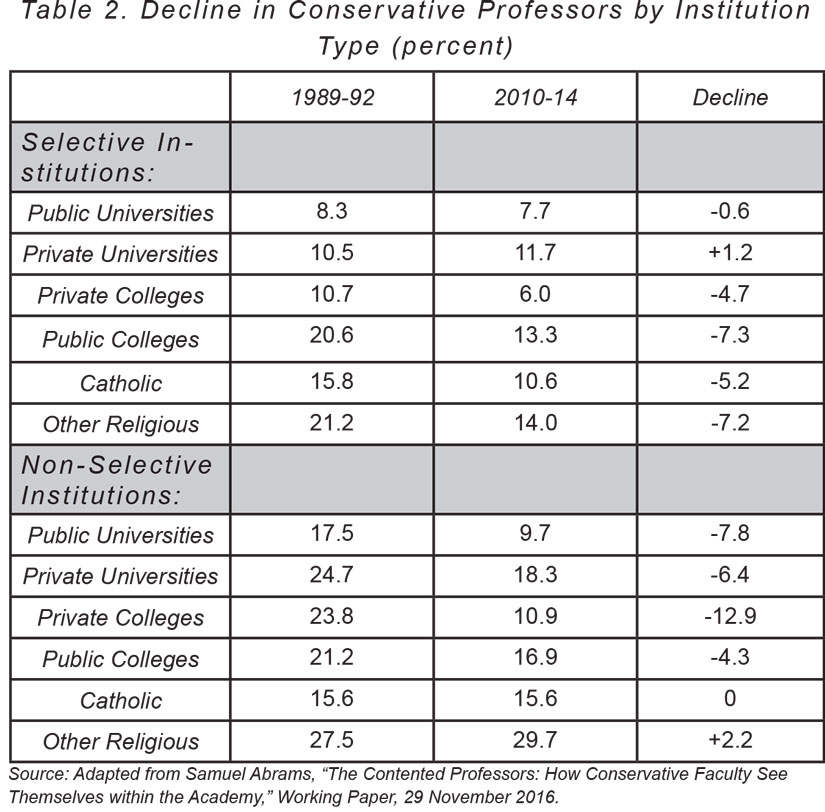

Notably, the decline of conservative professors has not occurred across all institutions. Conservative professors, for example, do not seem to be less common at elite research universities today than they were in the late 1980s and early 1990s, as shown in Table 2 below. The largest declines have occurred at undergraduate colleges and non-elite research universities. It is unclear why elite research institutions have been untouched by these changes, though it is possible that these institutions use less-politicized criteria when selecting faculty, and thus make it easier for talented conservative scholars to find jobs.

Although the declines were not as sharp, even religious institutions enjoy less political diversity in their faculty than they once did. Nonetheless, religious institutions — and Protestant colleges and universities in particular — remain far more diverse politically than secular ones, on average. Thus, if one wants to be exposed to a broad spectrum of political ideas, it is still far better to attend Notre Dame or Baylor than Berkeley or Cornell.

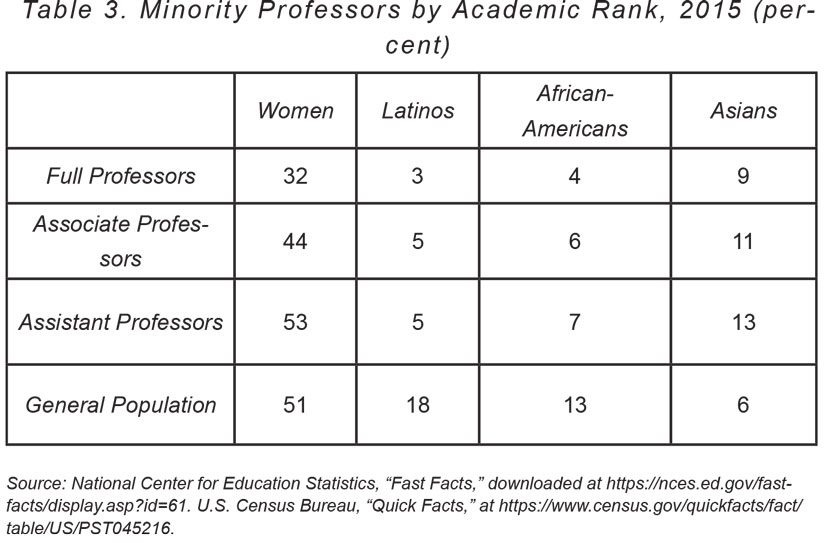

As conservative voices have faded from America's campuses, groups targeted by affirmative action have improved their numbers in recent decades. The representation of women, in particular, has increased dramatically: Women now earn a majority of PhDs and hold a majority of assistant professorships. They also hold about half of all professorships. These are among the recent changes in women's fortunes that have prompted some feminists to proclaim the coming "end of men."

To a degree, the aforementioned trends are connected. According to sociologist Neil Gross, while some 64% of male social scientists identify with the left, a remarkable 85% of female faculty do likewise. And because male faculty are more ideologically diverse than female faculty, the mass entry of women has meant fewer conservative thinkers in academia. Thus, as the male-dominated "greatest generation" began to retire in the late 1980s and early '90s, they were replaced by younger cohorts that were both more female and more uniformly on the left.

The progress of racial minorities — especially black and Latino professors — has been markedly slower, especially for African-Americans. Their numbers have not improved much since the late 1980s; according to the Digest of Education Statistics, 5.4% of professors were black in 2009, up from 5.1% in 1998. Latinos have not fared much better. Just 3.8% of academics were of Latino descent in 2009, up from 3.3% in 1998.

The academic pipeline, however, suggests that the representation of racial minorities will continue to improve, albeit at a slow rate. Black scholars, for example, hold a larger share of assistant professorships than full professorships. The same is true of Latino faculty, as shown in Table 3. While only 7% of full professors are either African-American or Latino, they make up some 12% of assistant professors.

WHY CONSERVATIVES GET DIVERSITY WRONG

One might reasonably conclude from such trends that increasing the number of conservative professors in academia should at least be part of university diversity initiatives. Conservatives, however, tend to push this case further by arguing that one should support only "real" or "actual" diversity, which, for most conservatives, means diversity of viewpoints. Indeed, they often point out that the growing demographic diversity in the university has only pushed the institution further leftward.

While such arguments correctly recognize the ways in which increased demographic diversity has pushed the university further to the left, they also tend to ignore or mock the ways in which these changes have brought new ideas and viewpoints into the academy.

When women entered the academy in large numbers, for example, they brought different intellectual interests and interpretations with them. They studied subjects that had long been neglected by their male predecessors. Thus, female professors broadened the interests of academia, even as they deepened and continued a long tradition of research on inequality, as well as other subjects associated with progressive politics. Women brought more leftism and more intellectual diversity.

Conservatives should hardly find it strange that a broad diversity of ideas can exist on one end of the political spectrum. After all, modern American conservatism is a tent that encompasses deep philosophical and intellectual differences. In researching our book on conservative professors, Joshua Dunn and I were reminded of these divisions and the seriousness with which conservatives take them. The conservatives we interviewed embraced a broad range of conservative identities, including Catholic conservative, Christian traditionalist, Christian humanist, communitarian conservative, constitutional conservative, paleoconservative, neoconservative, social conservative, natural-rights conservative, classical conservative, conservative libertarian, free-market conservative, and reactionary.

African-American scholars have had much less influence in academia than women, due to their comparatively small numbers. Nonetheless, even the small increase in black scholars during the 1970s and '80s brought more intellectual diversity into the university. In the 1980s, for example, some African-American scholars studied topics that many of their liberal white peers were either uninterested in or afraid to explore honestly — particularly the deteriorating conditions of black ghettos. As William Julius Wilson put it in The Truly Disadvantaged in 1987, "[L]iberal scholars shied away from researching behavior construed as unflattering or stigmatizing to particular racial minorities." In that anxious climate, it was easier for black scholars like Wilson to offer an unflinching account of the world of the black urban poor. It would have been a lot harder for critics to argue that black academics were out to denigrate disadvantaged blacks.

Some black scholars also have a unique angle on social questions because of their distinct social and cultural backgrounds. Consider Black Silent Majority, a recent book by Michael Fortner. It traces New York's draconian Rockefeller drug laws to a movement of working- and middle-class blacks, the group that suffered the most from the emerging drug trade in the 1960s and '70s. Fortner's thesis emerged partly from his own memories growing up in crime-ravaged Brooklyn. As Fortner recalled in the book's preface, "I remember a community at war with itself....Working- and middle-class families like mine were not deeply interested in civil rights or the politics of race....I remember black folks constantly worrying about keeping their children, homes, and property safe. These working- and middle-class families did not express much 'sympathy for and empathy with the perpetrators' of crime in the neighborhood." Likewise, Stephen Carter and Randall Kennedy have written powerfully about the costs of affirmative action (even though they support it), partly because they have experienced some of those costs. Unlike their white colleagues, Carter and Kennedy could not easily pretend that such tradeoffs did not exist.

Perhaps partly for this reason, black professors — especially at elite institutions — have been notably heterodox in their thinking about race, even though many lean left. Scholars such as Wilson, Carter, Kennedy, Orlando Patterson, John McWhorter, Elijah Anderson, Shelby Steele, and Glenn Loury have all been unusually contrarian thinkers, a depressingly rare tendency among social scientists today.

While conservatives are surely right to insist that there is no one "black perspective" on the social world, it is also folly to assume that social inquiry would not suffer if all scholars had the same social background. Consider research on religion, for example: George Marsden's groundbreaking work on fundamentalism or Robert Orsi's insights into Catholicism certainly owed something to their distinctive religious upbringings.

At times, conservatives have acknowledged the importance of religious diversity among the professoriate. Reflecting on religious scholarship, for example, James Q. Wilson noted that "[t]his is a matter to which scholars have given relatively little attention, because scholars, especially in the humanities and the social sciences, are disproportionately drawn from the ranks of people who are indifferent — or even hostile — to religion." Scholars from other backgrounds — working-class neighborhoods or the South, for instance — can also draw on their experiences to generate insights into the subjects they study.

In short, conservatives are right to insist that racial diversity does not always lead to intellectual diversity. But that is true of political diversity as well. Many conservative and libertarian professors study topics that are fairly removed from their politics. Such professors regard themselves as historians or political scientists who happen to be conservative, rather than distinctly conservative historians or political scientists. That fact, however, does not render political diversity an unimportant goal of the university.

WHY LIBERALS GET DIVERSITY WRONG

If conservatives too often dismiss the significance of gender and racial diversity in higher education, liberals are also typically unimpressed by appeals for more political diversity. Perhaps one reason some on the academic left are so unconcerned about a lack of viewpoint diversity is that they are especially attuned to the ways in which such diversity has increased in the postwar period.

Before women and blacks began offering a greater variety of academic perspectives, Jews had — particularly in the wake of World War II. As Everett Carll Ladd and Seymour Martin Lipset found in their classic 1975 study, The Divided Academy, Jewish academics brought an assortment of radical philosophical orientations — most notably Marxism — into American colleges. As Jews, women, and blacks continually increased viewpoint diversity over the course of decades, it became increasingly difficult for the academic left to understand conservatives who kept insisting that the university was becoming a homogenous institution.

Indeed, a growing body of empirical research suggests that many liberal academics are still unconcerned about the leftward tilt of the social sciences. A substantial minority of liberal professors are even willing to express a preference for hiring progressive colleagues. In Compromising Scholarship, a 2011 book by sociologist George Yancey, some 30% of sociologists acknowledged that they would be less likely to hire a job applicant if they knew he was a Republican. Yancey further discovered that 15% of political scientists and 24% of philosophy professors would discriminate against Republican job applicants, and at least 30% of professors in all disciplines surveyed would discriminate against members of the NRA.

Professors are even less tolerant of evangelicals, whom they associate with social conservatism. Nearly 60% of anthropologists, 50% of literature professors, 39% of political scientists and sociologists, 34% of philosophy professors, and 29% of historians say they would be less inclined to hire evangelicals. Yancey further found that female professors expressed more anti-conservative bias than men, perhaps in part because female professors tend to be more progressive than their male peers. Thus, as gender diversity has increased, the university may have become less welcoming to conservatives.

Other research suggests that liberal professors sometimes act on these biases. Stanley Rothman and Robert Lichter found in 2009's The Politically Correct University that socially conservative professors tend to work at lower-ranked institutions than their publication records would suggest. More recently, a 2016 study of elite law schools in the Harvard Journal of Law and Public Policy found that libertarian and conservative professors publish more than their peers, which suggests that right-leaning law professors must outshine liberals to reach the summits of their profession.

These findings are especially striking given that other research shows it is more difficult for scholars to publish work that reflects conservative interests and perspectives. A 1985 study in the American Psychologist, for example, assessed the outcomes of research proposals submitted to human subject committees. Some of the proposals were aimed at studying job discrimination against racial minorities, women, short people, and those who are obese. Other proposals set out to study "reverse discrimination" against whites. All of the proposals, however, offered identical research designs. The study found that the proposals on reverse discrimination were the hardest to get approved, often because their research designs were scrutinized more thoroughly. In some cases, though, the reviewers raised explicitly political concerns; as one reviewer argued, "The findings could set affirmative action back 20 years if it came out that women were asked to interview more often for managerial positions than men with a stronger vitae."

Fair-minded liberals, however, must ask themselves an important question: How seriously do they take the "diversity rationale" expressed in Regents of the University of California v. Bakke? Citing an earlier decision, the Supreme Court in that case declared: "The Nation's future depends upon leaders trained through wide exposure to that robust exchange of ideas which discovers truth 'out of a multitude of tongues.'" Hasn't the wisdom of Bakke been confirmed by the increase of gender and racial diversity in the university? And if women and blacks brought considerable intellectual diversity to academia, why couldn't Burkeans and libertarians do the same? If one believes that gender and racial diversity contribute to a "multitude of tongues" in the university, on what conceivable grounds can one claim that conservative and libertarian voices do not? Any sincere commitment to diversity must include a concern for political diversity, especially at a time when conservative and libertarian professors are disappearing from our campuses.

Some progressives might insist that the diversity rationale is weak and has been foisted upon them by the Supreme Court. As Harvard law professor Randall Kennedy has observed, the Bakke case provided universities with "a strong incentive to engage in diversity talk." The campaign for more political diversity in the university is haunted by the possibility that much of this "diversity talk" is insincere.

Such critics might also ask why, if the rationale for increasing the diversity of the university is rooted in a kind of restitution toward women and minorities, we should be concerned about the scarcity of conservative academics, most of whom are white men. In this view, a commitment to increasing gender and racial diversity does not demand any similar effort to improve political diversity. The case for political diversity simply rests on a different premise, and, to some progressives, it isn't all that compelling.

But if that's right, then universities should treat blacks differently than women and Latinos. Our nation, after all, hardly subjected women or Latinos to anything resembling chattel slavery. If the point of affirmative action is to create equal opportunity by remedying a legacy of discrimination, then surely blacks deserve far more assistance than other groups, especially women. As Richard Kahlenberg pointed out years ago, the "compensatory argument did not work well for women" in particular. "[W]hite women," noted Kahlenberg, "are much less economically disadvantaged than blacks and can readily compete in a number of educational and employment arenas without preference."

Even progressives who are sincere about the diversity rationale, however, may find it challenging to eagerly recruit conservatives. Unlike irrational racial or gender prejudices, our political biases often express an intellectual orientation—one that shapes the way we assess scholarship. Our politics, after all, inclines us to find some questions more important than others and some explanations more plausible. It is partly these biases that make political diversity important in the first place. As David Hull, a philosopher of science, explained, "One of the strengths of science is that it does not require that scientists be unbiased, only that different scientists have different biases." Thus, any push for political diversity in the university presents a unique challenge: Universities must somehow check biases that are both natural and critical to the overall health of the university.

STRUCTURAL OBSTACLES

The personal preferences and biases of liberal academics, formidable as they may be, are not the most significant obstacle to improving the representation of conservatives in the social sciences and humanities. There are deeper, structural reasons that make it difficult to improve the ideological diversity of the professoriate.

Perhaps the greatest obstacle is the way in which leftist interests and interpretations have been baked into many humanistic disciplines. As sociologist Christian Smith has noted, many social sciences developed not out of a disinterested pursuit of social and political phenomena, but rather out of a commitment to "realizing the emancipation, equality, and moral affirmation of all human beings as autonomous, self-directing, individual agents." This progressive project is deeply embedded in a number of disciplines, especially sociology, psychology, history, and literature.

That so many disciplines have been profoundly shaped by a progressive spiritual project renders them far less interesting to conservative students, which is at least partly why they are far more likely to rush into the hard sciences than their liberal peers. A 2006 study by Stephen Porter and Paul Umbach published in Research in Higher Education found that the political leanings of students were very strong predictors of their college majors. And because conservatives are less likely to major in the social sciences or humanities as undergraduates than their liberal peers, conservatives also gravitate toward the physical sciences in graduate school.

Notably, the tendency of conservatives to avoid classes and majors in the social sciences and humanities seems to have little to do with their interest in politics. As Amy Binder and Kate Wood found in their study of conservative campus groups, right-wing student activists tend to avoid majors in the social sciences and humanities. Thus, even conservatives who are unusually interested in the political and social world avoid majors that would allow them to study that world.

The exception that proves the rule is the field of economics. Economics is the only major in the social sciences that attracts conservative students in significant numbers, and it continues to draw a large share of them to graduate programs. This is hardly surprising; after all, economics is the only social-scientific field that has been deeply shaped by figures who are part of the conservative intellectual tradition, including 20th-century thinkers like Milton Friedman, Friedrich Hayek, and James Buchanan.

Thus, even if all professors were impartially handing down their discipline's body of knowledge — indeed, even if they went out of their way to welcome conservative students — we would still expect conservative undergraduates to be less drawn to majors that have been shaped by progressive interests and interpretations. And that means that the leftward tilt of the social sciences and humanities is self-reinforcing. As the left has often appreciated in other contexts, the most intractable inequalities are often sustained because of structural causes rather than personal animus.

Compounding this structural obstacle is the growing political polarization of American society. The American right has pushed young conservatives away from the university for decades by lampooning its leftism and overstating its intolerance. A recent Pew survey found that a substantial majority of Republicans now think that universities have a negative effect on the nation. It would be a tragic irony if today's right-wing youth were to follow the lead of student radicals from the '60s by insisting that the university is irredeemable and must be burnt to the ground.

The right's recent populist turn also promises to depress the appeal of conservatism, particularly on America's most elite college campuses. As Binder and Wood found in their research on an Ivy League campus, the most elite conservative students are wedded to deliberative engagement with those with whom they disagree. They steadfastly reject the aggressive, bombastic style that has come to characterize Donald Trump's presidency and so much of American conservatism. If such trends continue, we can expect even fewer conservative students to pursue graduate work.

CAN CONSERVATIVES RETURN TO THE UNIVERSITY?

In the face of these daunting challenges, it is encouraging that at least some moderate and liberal professors have recently expressed their support for more political diversity in the academy. As of this writing, more than 2,000 professors and graduate students have joined the Heterodox Academy, an organization that is expressly concerned with the absence of center-right thinkers in many areas of the social sciences and humanities. Notably, this group does not simply attract libertarians and conservatives. According to a recent survey, some 42% of Heterodox Academy members regard themselves as progressives or centrists. Whether this coalition is broad and serious enough to weaken these structural obstacles, however, remains to be seen.

If right-of-center academics are to gain a firmer foothold in the academy, the debate about why there are so few of them, and whether there ought to be more, will require much greater self-awareness on all sides. Conservatives in and out of the academy will need to acknowledge that, while there is very real discrimination in academic hiring, there are also structural factors that are keeping intellectually minded people on the right from pursuing the academic career track. And if they want to make a case for political and intellectual diversity, they should at least acknowledge the legitimacy of the case for the kinds of diversity favored by the left.

Progressives, meanwhile, both in and out of the academy, will need to confront the strong evidence of political bias in academia. And they will need to face the contradiction inherent in accepting a diversity rationale for affirmative action while rejecting the case for political and intellectual diversity.

If the university in America is to serve as a force for unity, and to resist rather than exacerbate the intense and increasingly destructive polarization of our common life, its denizens will need to be more consistent and coherent in how they approach the question of diversity on campus. And they will need to take a broader, deeper view of the purpose of higher education in a free society. This is no easy task, but it is an essential one.