The Contested Meaning of Women's Equality

On January 15, 2020, the General Assembly of the Commonwealth of Virginia passed a ratification resolution in favor of the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA). Proponents suggest that since Virginia was the 38th state to affirm such a resolution, the amendment is now officially part of the U.S. Constitution. Attorneys general for Virginia and two other states have filed suit against the archivist of the United States to make it so.

Opponents disagree. Not only has the congressional deadline for ratifying the ERA long since passed, but five of the states that proponents count among the three-quarters necessary for ratification voted to rescind their ratification resolutions four decades ago. Had earlier congressional deadlines been of no consequence — one of the many arguments proponents make — the amendment would still be several states short of the requirements. To the chagrin of proponents, even the late Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg once acknowledged that it was time to start the process all over again.

What may be lost in legal squabbles over ratification procedure is an important substantive point: Although the amendment's text — and the strict equality it enunciates — remain the same, the disputed ERA of 2020 is simply not the same animal the 92nd Congress sent out for ratification in 1972. Congress and the courts have already put into place nearly everything the ERA proponents of the 1970s sought: the removal of sex-based legal distinctions in myriad areas of the law, prohibitions against overt sex discrimination in the workplace, laws in favor of equal educational and athletic opportunities, and laws requiring equal pay for equal work. Indeed, the successful legislative and litigation strategies women's-rights advocates pursued in the early 1970s have given way to a "de facto ERA," as some scholars have put it, making the ERA of 1972 constitutionally unnecessary. So why the elaborate attempt to push it through now?

Proponents maintain that ratifying the amendment Alice Paul penned nearly a century ago would be an important symbolic gesture of historic significance and ensure that the political and constitutional gains of the last half-century will not be undone. The phrase "[e]quality of rights under the law shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex" would finally be enshrined in the country's foundational legal text — in the year the nation celebrates the centennial of the 19th Amendment, no less.

Yet whatever their public-relations campaign says, those who work for the ERA's passage today are not merely interested in symbolic gestures, or even in securing extant anti-discrimination law. Rather, they seek to ratify constitutionally the same philosophical ideal Paul first sought in the 1920s, but with altogether new targets in mind. If history is any indicator, they will fail for the same reason Paul and successor after successor failed: Abstract ideals of equality do not account adequately for the concrete duties of care that, relative to men, women disproportionately continue to undertake.

ERA advocates are right to seek better workplace accommodations for pregnant women, better treatment of working mothers, and better public support for child-raising families, among other less-savory goals. Yet however much we might like our daughters and sons to see their fundamental equality emblazoned in the text of the Constitution, strict equality will not give mothers and fathers the support they need. A more intentional and robust family policy, on the other hand, just might.

PHILOSOPHICAL UNDERPINNINGS

Riding the wave of several state victories granting women the right to vote in state and presidential elections, Alice Paul and her National Woman's Party brought the 19th Amendment to successful ratification on August 26, 1920. Within months of this victory, Paul began working toward what seemed the next logical goal: the ERA. In 1922 she declared, "[t]he work of the National Woman's Party is to take sex out of the law — to give women the equality in the law they have won at the polls."

Yet not all members of the women's-rights movement lined up behind Paul's endeavor. In the decades to come, a debate over the text of the ERA ensued, intersecting with the movement's contemporaneous debate over protective labor legislation for working women in the midst of the Industrial Revolution. Both debates revealed the deep philosophical differences between the two wings of the women's-rights movement — differences that shot through advocacy for women's rights almost from its beginnings.

The earliest thread emerged from Mary Wollstonecraft's 1792 treatise, A Vindication of the Rights of Woman — the authoritative text for early women's-rights advocates in the United States. A second work, which had more influence on the ERA and the modern women's-rights movement, was John Stuart Mill's Subjection of Women, published in 1869. In their respective works, both Wollstonecraft and Mill pushed for women's equality in marriage, in education, in the professions, and as citizens. And both suggested that women's true capacities would remain unknown until they had equal access to education and more serious-minded occupations — just as advocates in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance had argued before them. But their distinctive philosophical claims bore out over time in radically different reform measures among their respective adherents in America.

A deeply misunderstood figure, Wollstonecraft offered a defense of rights too often simplistically assumed to be in strict keeping with John Locke's account. The moral purpose underlying her claims, meanwhile, remains sorely neglected. For Wollstonecraft, republican government need not look back to a myth of origin for its legitimate foundations. Rather, our given nature as rational creatures created by and responsible to God supplies a principled criterion upon which to discern our concrete duties to God, self, and others, as well as the rights each person requires to virtuously carry them out. Persons are equal in dignity, Wollstonecraft explained, because each one, whatever his or her starting point, is a rational creature capable of moral development. Each person, then, should be justly afforded the intellectual and moral formation he or she needs "to rise in excellence by the exercise of powers implanted for that purpose" — regardless of sex.

Like Wollstonecraft, Mill recognized the injustice inherent in women's unequal legal and social status. However, his argument leaned on a characteristically utilitarian rationale. For Mill, the subordination of women to men was not only a wrong, but also a detriment to human improvement and the enrichment of society as a whole. Recognizing women's rights to education, self-development, and the vote would, as Mill wrote, "doubl[e] the mass of mental faculties available for the higher service of humanity."

Few women's-rights advocates then or now would argue with Mill's book-length description of the problem. And the strict equality principle he advocated in response — "perfect equality, admitting no power or privilege on the one side, nor disability on the other" — certainly made good sense in those areas of the law where reproductive differences are of no consequence. But this same principle would be employed over time to denigrate those very differences and, in turn, devalue the culturally essential caregiving work in which women are still disproportionately engaged.

For her part, Wollstonecraft maintained that the virtuous development of persons — and thereby, societies — is the very purpose of life. Thus, the work of the home, and especially the shared maternal and paternal task of inculcating virtue in children, is the most essential of all human work. As such, she advocated not a "perfect equality" between the sexes, but rather recognition of an equal moral dignity that admits both the "power" and the "privilege" — and the "disability," too — of child-bearing and child-rearing, seeking not erasure of these facts, but a reconciliation of them within relationships of reciprocity, interdependence, collaboration, and mutual respect in all realms of life.

EARLY DEBATES

The ERA emerged from debates among women's-rights advocates over late 19th- and early 20th-century labor legislation, in which these philosophical differences were implicit. Such debates would ultimately reach the U.S. Supreme Court, beginning most famously in 1905 with Lochner v. New York. In that case, the Court struck down a regulation limiting the number of hours men in the baking industry could work, holding that the law illicitly impinged on the "liberty of contract" specially protected by the Due Process Clause of the 14th Amendment.

Advocating an implicitly Millian position, Alice Paul believed that the Lochner Court's upgrading of liberty of contract to the status of a constitutional right was a certain path toward expanding married women's legal capacity to contract, which was still curtailed in many states by coverture. If women were going to provide for themselves and their families in these desperate times, Paul reasoned, they would have to be equally free to contract with employers for the number of hours they needed to work.

Paul's chief adversary, prominent social reformer Florence Kelley, opposed Lochner. Kelley argued that "liberty of contract" was increasingly a legal fiction that ignored the growing inequality of bargaining power between industrial capitalists and powerless laborers. She suggested that women, who at the time did not enjoy the protection of trade unions that men did, were especially vulnerable to maltreatment in the industrial workplace. Protective legislation for women would serve as a first step toward protective labor laws for all workers — and one day, perhaps, a more just economic system for the family and the nation as a whole.

While Paul believed strict equality between the sexes would best serve women's needs as individuals, Kelley maintained that Paul's insistence on "theoretical equality" would block the gains women were making in the industrial workplace, and perhaps those of men as well. In Paul's quest, Kelley saw a threat of subjecting women, along with men, to exploitation in the economy. Instead, Kelley and her allies argued for "specific bills for specific ills" — a legislative possibility that would become more likely once women won the franchise.

In her book Some Ethical Gains through Legislation, Kelley argued that industrialization had forced women and children into the workforce, offering them poor wages and reprehensible conditions and ultimately disrupting family life among the working class. Reminiscent of Wollstonecraft's prioritization of domestic life as the seedbed of public virtue, Kelley's writings asserted that children's nurturing and education ought not be sacrificed at the altar of the industrial marketplace.

True liberty of contract, she further contended, could only be built on a familial and communal substructure that took seriously the responsibilities that parents had to their children and that employers had to their employees. Recalling an older tradition, Kelley suggested that the Due Process Clause did not grant the Supreme Court authority to strike down statutes simply because the justices found them unwise — just as Justice John Marshall Harlan had argued in his Lochner dissent. Rather, it provided a procedural safeguard in favor of duly promulgated legislation on behalf of the common good.

To ensure her lobbying efforts in favor of state-based labor reforms would stick in Lochner's wake, Kelley acquired the legal assistance of future Supreme Court justice Louis Brandeis, who argued in support of maximum-hours laws for women at the High Court. Rendering an opinion that remains deeply controversial today, the Court in Muller v. Oregon upheld the women-protective labor law, distinguishing it from Lochner and vindicating Kelley's position. Following Brandeis's logic, the Court reasoned that maternity placed working women "at a disadvantage in the struggle for subsistence," and so legislation could licitly "compensate for some of the burdens which rest upon [them]." Then in 1917, this time with the legal aid of future justice Felix Frankfurter, Kelley's allies convinced the Court to uphold a maximum-hours law for men as well.

Minimum-wage laws for women became the next flashpoint of debate, just as Paul was engaging Kelley and her protectionist allies in negotiations over the language of the newly proposed ERA. Their discussion led to an early draft that exempted protective legislation from strict equality's purview "on the basis of the physical constitution of women," but this language satisfied neither side and was ultimately dropped. Paul eventually broke off discussions with Kelley's allies, and the ERA became the "blanket bill" articulating the formal equality for which Paul had initially hoped. As historian Nancy Cott observed:

[Paul's organization] looked at women as individuals and wanted to dislodge gender differentiation from the labor market. Their opponents looked at women as members of families — daughters, wives, mothers, and widows with family responsibilities — and believed that the promise of "mere equality" did not sufficiently take those responsibilities into account.

In 1923, the Court swung back in Paul's direction. Three years after the 19th Amendment's ratification, the Court struck down a minimum-wage law for women, resting its reasoning on the "revolutionary" changes to the status of women that had culminated in the franchise while also resurrecting the substantive-due-process principles of Lochner. Paul, who had assisted the hospital's attorneys in Adkins v. Children's Hospital, was elated with Justice George Sutherland's majority opinion: Not only did he insist that the differences between the sexes had "come almost, if not quite, to the vanishing point," he also argued that women were "legally as capable of contracting for themselves as men." With her view of sexual equality vindicated at the Court, Paul's organization moved swiftly to introduce the ERA in Congress.

Kelley's own response to the Court's decision in Adkins was equally swift. Highlighting the alliance of Paul's equal-rights advocacy with the commercial interests that had lobbied against the minimum-wage law, Kelley quipped, "[t]he women who pretend to be making heroic exertions to get ‘equal rights' for all women are, in practice, the Little Sisters of the United States Chamber of Commerce." Paul's vision, at the heart of which stood the ERA, was to Kelley a capitulation to the commercial ethos that an earlier generation of women's-rights advocates had fought hard to resist.

FROM LABOR LEGISLATION TO ANTI-DISCRIMINATION LAW

Paul's win in Adkins was short lived. After Franklin Roosevelt's landslide victory in 1936 and his court-packing proposal, the Court changed course once again, reversing Adkins and upholding a minimum-wage law for women. Kelley herself passed away in 1932, but thanks to the women who took on leadership roles throughout FDR's administration — including Kelley's protégé, Frances Perkins — her strategy led to labor laws protective of both women and men in the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) of 1938. The act at its origins was deeply flawed — excluding from coverage those industries predominated by women and black workers as well as those untouched by unionization — but subsequent decades saw coverage expand to nearly 90% of workers by the 1970s.

As the years wore on and greater numbers of women entered the workforce (especially during World War II), the ERA gained little traction despite being introduced in every session of Congress. In 1946, former first lady Eleanor Roosevelt and several other leading women's labor advocates issued a statement arguing that the ERA would "make it possible to wipe out the legislation which has been enacted in many states for the special needs of women in industry." That same year, the amendment failed to win the two-thirds majority required in the Senate. The following decade, a version of the ERA passed the Senate but with a rider similar in purpose to that first requested by labor advocates, and it was ultimately withdrawn. Kelley's early depiction of the ERA as the blunt instrument of elite professional women siding with business interests against poor and working-class mothers would stick — at least until the late 1960s.

As the ERA languished in committee, activists continued to achieve slow but steady progress for women in the workplace, advocating, as their predecessors did, "specific bills for specific ills." With federal laws now providing a minimum floor of protection for many workers, they looked to ensure women did not receive unjust treatment in the workplace simply because of their sex. In 1963, responding to a major report drawn up by the President's Commission on the Status of Women, Congress passed the Equal Pay Act, amending the FLSA to outlaw sex-based wage discrimination. Congress then banned sex discrimination in employment via Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

The president's commission also recommended, at the behest of leading civil-rights attorney Pauli Murray, that advocates bring test cases to the courts to clarify the legal status of women under the Constitution. Murray's position was akin to that of suffragist litigators who had argued a century earlier that because women were both "persons" and "citizens," they ought not be denied "the equal protection of the laws" conferred by the 14th Amendment. From Murray's perspective, a more capacious interpretation of the Constitution might make the bluntly worded ERA — still contested by women's labor advocates as likely to eliminate maternity legislation for women — legally unnecessary. Incrementalism, which had proven successful in the race context and was inherent to a case-by-case strategy, began to reveal its own appeal.

Relying on Murray's arguments, Ruth Bader Ginsburg — then an attorney for the American Civil Liberties Union — convinced the Supreme Court in a series of early 1970s cases that, just as states could not discriminate on the basis of race, they ought not licitly discriminate on the basis of sex, either — at least when biological differences were not at issue. Murray and Ginsburg contended — as Wollstonecraft, Mill, and others had before them — that biological differences had historically been used to denigrate women's rational capacities as a class; the Constitution, on the other hand, required persons to be judged individually on their merits. "When biological differences are not related to the activity in question," Ginsburg contended in her brief in Reed v. Reed, "sex-based discrimination clashes with...equal treatment." A unanimous Court struck down the sex-based probate law as lacking any rational basis. Though the justices did not accede to Ginsburg's request then or in any of the following cases to review sex-based laws strictly, the Court eventually settled on an intermediate standard of review.

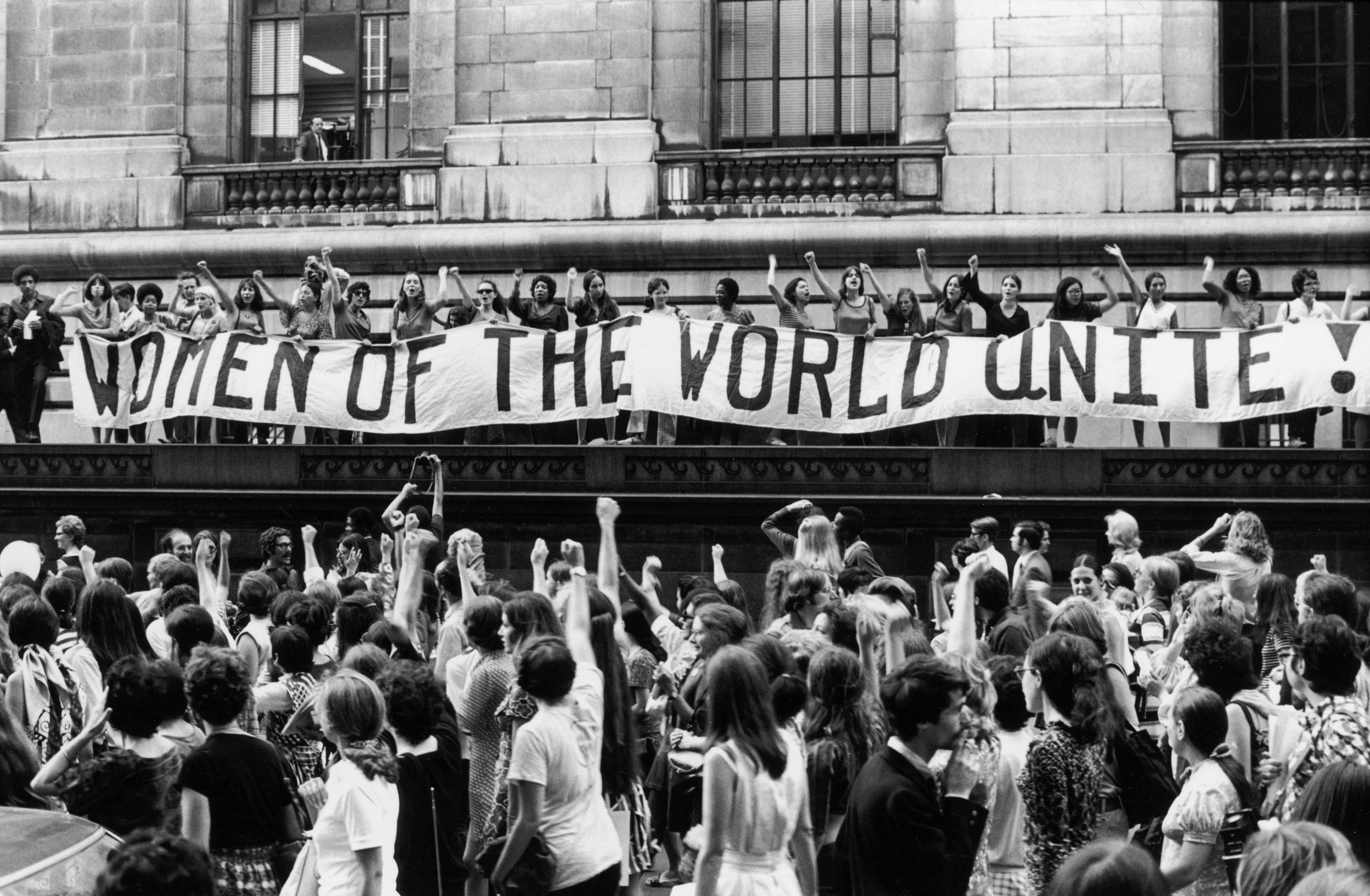

Riding the coattails of the civil-rights movement's successes, the ERA finally passed the House the same year the Court handed down Reed — by very large margins. The Senate passed the amendment a year later, appending a seven-year deadline for ratification by the states. By 1973, the amendment had easily won ratification in 30 state legislatures. But after the Court decided Roe v. Wade that same year, the ERA quickly became associated with abortion rights, even as anti-ERA forces — Phyllis Schlafly foremost among them — convincingly brought additional concerns to the public's attention.

ABORTION AS EQUALITY, PREGNANCY AS DISABILITY

Although ERA advocates had promised in the years before and after Roe that the amendment would not touch the abortion question, feminist attorneys had begun to make equality arguments for abortion rights by the early 1970s. These efforts betrayed a real hope for the ERA, which dominates advocacy in our own time.

Suggesting perfect equality would require women to enjoy the same kind of reproductive autonomy men seemed to enjoy — the freedom to walk away from the consequences of sex — these feminists promoted a version of equality that was radical even for Mill. Rather than expect men to meet women at a high standard of care, as Wollstonecraft had insisted, or demand that profit-driven workplaces acknowledge the responsibilities of family life, as Kelley had argued, this new vision of equality would rather mimic the sexual and workplace experiences of unencumbered men. To close observers, this line of argument seemed to imply that pregnancy and motherhood were themselves impediments to sexual equality.

Indeed, in the wake of the 1973 abortion decision, employers who excluded pregnancy from health insurance or disability coverage found themselves with an additional argument for their position: Pregnancy after Roe could be understood as a condition affirmatively chosen by a woman and thus not quite comparable with otherwise disabling conditions covered by insurance. The attorneys representing California in the 1974 case Geduldig v. Aiello — involving a challenge to a state disability-insurance program that excluded disabilities resulting from pregnancy — took full advantage of this new argument: "[A] large part of woman's struggle for equality," they argued in their brief, "involves gaining social acceptance for roles alternative to childbearing and childrearing." And pregnancy post-Roe had become "voluntary, and subject to planning." In the meantime, large companies moved to ensure that abortions — which were less expensive than pregnancy — were funded in their health-insurance plans even as the impetus to offer maternity leave began to wane.

The Court ruled in favor of the employers in Geduldig on other grounds, holding that excluding pregnancy from disability coverage did not constitute sex discrimination. Two years later, the Court held that Title VII also did not require employers to include pregnancy in disability coverage. Congress responded by passing the Pregnancy Discrimination Act (PDA) in 1978, fitting its remedy within this comparatist view of sex discrimination. Pregnant workers, the law asserted, must be afforded the same treatment as non-pregnant workers who are otherwise "similar in their ability or inability to work." In other words, pregnancy was analogized to disability.

The question quickly arose as to whether the PDA prohibited greater allowances for pregnant women and mothers when states elected to make them. Thus, when in 1978 California required employers to allocate four months unpaid leave to women upon the birth of their child, employers brought suit in federal court, alleging that the law violated the PDA by requiring pregnant workers be treated better than others — in other words, the law discriminated against men.

Just as women's advocates during the Lochner era took opposite sides concerning protective labor legislation for women, so too did feminist attorneys advocate on both sides of the new pregnancy-related issue. The chief architects of the PDA took the employers' side: By singling out pregnancy for "special treatment," they argued, California would make women costlier than men to employ and therefore create disincentives to hiring them.

On the other side sat labor advocates who echoed Florence Kelley's early 20th-century concern that strict equality abstracted from, and so tended to ignore, the actual experiences of women. Likewise, members of the Coalition for Reproductive Equality in the Workplace (CREW) suggested that while the PDA would ensure that these women did not lose their jobs, the lack of a leave policy would not guarantee them sufficient time to recover from childbirth or to nurture their infant children. Much like their predecessors, members of CREW argued that such women-specific benefits did not prefer women to men, but rather took into account the asymmetries of human reproduction and so rightly acted as a kind of equalizer.

In 1987, the Supreme Court sided with CREW, ruling that the PDA did not preempt more generous maternity policies. Six years later, the Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA) linked family and sick leave within a gender-neutral federal policy. Congressional proponents of the new law successfully argued that "denial or curtailment of women's employment opportunities has been traceable directly to the pervasive presumption that women are mothers first, and workers second."

A welcome if modest step in a cultural landscape otherwise bereft of affirmative support for child-raising families, the FMLA continues to be irrelevant for disadvantaged mothers who cannot afford to take unpaid leave. Harrowing stories of poor women returning to work days after childbirth recall the situation to which Kelley and her allies were responding during the industrial era.

Today, many now falsely assume that universal daycare will fix such parental ills, providing infants and very young children the care they need to allow mothers to go back to work. Yet most mothers (and fathers) do not want to be displaced from their caregiving responsibilities; on the contrary, they see the caregiving they do — and the deep, intimate, irreplaceable relationships it fosters — as a great power and privilege, even as their active presence in their children's young lives redounds to their children's lifelong advantage. These parents instead seek support in lessening the "disability" that caregiving imposes on their families financially and professionally.

The primary trouble for work-family reconciliation, then, is not so much that women are too often regarded as "mothers first and employees second," as the FMLA's sponsors supposed. Rather, the more fundamental problem is that all people in the workplace are presumed to be employees first and caregivers second. Once regarded respectively as breadwinners and caregivers, both men and women are now expected to prioritize breadwinning. On this view, gender equality will only advance when women and men are equal winners of their family's bread. Indeed, this is precisely the view of equality that ERA proponents want to impose.

But the Millian paradigm that seeks above all to "doubl[e] the mass of mental faculties" for the economy misses a more basic insight from Wollstonecraft, shared also by Kelley: Stable, just, and flourishing societies rest on the integrity, ingenuity, and industry of persons, as well as the relationships of interdependence, trust, and fair play among persons. These virtues are first learned in families or not at all. Only a higher viewpoint — one that sees the economy in service of families and its members, not vice versa — will provide the underlying rationale for a humane work-family agenda. As Mary Ann Glendon put it, "[t]hink of it: human values ahead of economic values, the dignity of all types of Work. That is a radical program. It goes to the root of the materialism of both capitalist and socialist societies as we have known them."

SUPPORTING MOTHERS AND FATHERS

The Covid-19 pandemic has made clearer a truth that was once mired in political debates: that better work-family reconciliation policies are not only necessary for the economy to function, they are also indispensable for promoting the well-being of families in the culturally essential, civilization-shaping work they do. As much as many have complained about the lack of child care in these trying times — and women in particular have struggled to carry out both work and home responsibilities simultaneously — many have also relished the time they've been able to spend with their children, time they may not have known they'd been missing.

If it is to properly recognize the work of the home as foundational to every other public good, the state, acting on behalf of the community at large, must take the lead in adopting family-supporting policies today, renewing once more the nation's commitment to family life. Not only should the state require (or incentivize) employers in every sector of the economy to provide a strong mix of family-reconciling work policies — flex time, predictable scheduling, part-time pay equity, job sharing, telecommuting, results-based reviews, paid leave, on-site care, and the like — but lawmakers must also adopt greater supports for caregiving families from among the array of existing proposals while generating new ideas, from paid leave, to more generous child tax credits or allowances, to earned Social Security credits for stay-at-home parents, to waiving the personal income tax for those who have dedicated a substantial portion of their lives to raising children and caring for family members. To recognize the transcendent value of the work of the home — and thereby short circuit the logic of the consumerist market that tends to conform all human relations to itself — a key principle that must guide any policy is this: Government ought not discriminate in favor of families who contract out their caregiving over those who seek to care for their own children and other dependents in their own homes.

Other work-family reconciliation measures should be taken as well. Cognizant of the asymmetrical burdens borne by women workers, half of the states and a few localities have passed pregnant-worker fairness statutes requiring reasonable accommodations for pregnant employees without a prior showing of comparative disability. Congress ought to act in like manner. Additionally, anti-discrimination law ought to better recognize discrimination on the basis of caregiving responsibilities to ensure employees are judged on their capacity to do their job, not on the false assumption that being a parent or reducing one's time at work to engage in caregiving makes them a less competent or committed employee.

An ERA that requires courts to strictly scrutinize state policy such that it treats women and men perfectly alike would jeopardize just those policies that might best assist child-raising families — and the women who continue to engage in most caregiving activities in particular. Policies that seem to prefer women to men (like pregnant-worker fairness statutes) or that are facially neutral but accessed by women far more often than by men (as work-family policies always are), would fare far better under current equal-protection jurisprudence than they would under the ERA. Current case law allows for the fact that, as Justice Ginsburg herself famously wrote in United States v. Virginia, "[t]he two sexes are not fungible."

What's more, deregulating and funding abortion at the behest of strict equality would only strengthen the already too prevalent view that to be unencumbered by obligations to dependents is to be a responsible and committed employee. Under such a paradigm, child-bearing and -rearing would remain, in the logic of the market, but a substantial cost to employers and the community at large rather than an ordinary and rightly celebrated part of our common life.

Would that we instead vindicate the equality of the sexes as Wollstonecraft once did: by acknowledging that men and women share equally in the human capacity for excellence, but also that their excellence is most manifest not in their value to the market economy, but in the shared and reciprocal responsibilities they undertake as mothers and fathers, sons and daughters, sisters and brothers, citizens, colleagues, and friends. As Wollstonecraft poignantly put it, "society is not properly organized which does not compel men and women to discharge their respective duties." Today, these duties might be best compelled if they were but better recognized, prioritized, and supported.