Rethinking Redistribution

Too often, the ends that policymakers pursue are poorly served by the means through which they pursue them. Examples of this problem abound today — but the clearest must surely be federal policymakers' efforts to combat poverty through the redistribution of income.

Like the governments of all other modern democracies, the United States government redistributes the incomes of its citizens on a massive scale. And in America, as elsewhere, the public generally supports such redistribution in principle, on the understanding that it is intended to help the poor. The lives of the needy, the argument goes, would be far worse without this aid, and presumably such redistribution is designed to avoid undue harm to everyone else.

Whether one agrees with it or not, this popular understanding of redistribution's purpose yields some useful criteria for assessing the degree to which our redistribution programs are actually succeeding. The aims of helping the poor and minimizing harm to everyone else, in other words, offer some specific ends against which our means of redistribution can be tested.

By and large, those means take three forms. First, there are direct anti-poverty programs, like Temporary Assistance to Needy Families (what we commonly think of as welfare), food stamps, Medicaid, and the Earned Income Tax Credit. Second, there is progressive taxation, which transfers wealth from richer to poorer Americans across the income distribution. And third, there are policies that tilt economic outcomes in specific markets to benefit people with lower incomes (minimum-wage laws are a classic example).

These programs are well entrenched in our public life, and each has its own assertive army of supporters. But when these programs are measured against the goals for which they are employed, they reveal an approach to redistribution that is both misguided and excessive. Almost all of our means of redistribution today lack convincing philosophical or empirical justification. They are poorly targeted, expensive, economically inefficient, and in many cases do more harm than good.

Our approach to redistribution thus requires a profound re-orientation. We need to think through the relationship between what such programs should aim to do and what the programs we now have actually do. We need to get back to basics, and ask what a straightforward and economically rational approach to alleviating poverty would look like. Above all, the federal government must focus its anti-poverty efforts on the people most deserving of help, while minimizing the cost to everyone else. Though this sounds like common sense, it is far from today's reality.

MEANS AND ENDS

The scope of income redistribution in America is truly immense. In 2007, the last year not significantly affected by the Great Recession, the federal government spent about $1.45 trillion (roughly half of its total spending) on programs aimed at redistributing income from more wealthy Americans to the less wealthy. These ranged from means-tested entitlement programs like Medicaid, housing assistance, unemployment compensation, and food stamps to broader entitlements like Medicare and Social Security (which are not means-tested, but nonetheless transfer income on a mass scale and are generally justified on the grounds that they reduce poverty among the elderly).

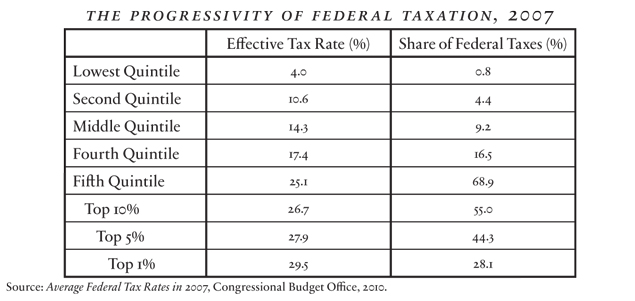

Beyond these direct anti-poverty initiatives, the progressive federal income tax redistributes income even further. Progressive taxation means that the tax rate increases along with a taxpayer's income; a person earning $50,000 per year, for example, might pay $10,000 in taxes while a person earning $100,000 per year might pay $30,000. The higher-income person not only pays more taxes in total: He also pays a larger portion of his income (30% versus 20% in the preceding example). The wealthier give up a greater share of their earnings so that the less wealthy can forfeit a smaller portion of theirs; in this way, our progressive tax code is redistributive. The table below displays the effective tax rate (defined as total federal taxes paid — including payroll taxes to fund Social Security and Medicare — divided by total income earned) for different segments of the income distribution. It also shows the share of the nation's total federal tax burden shouldered by each income group.

The table depicts an immense project of redistribution. In 2007, the poorest 20% of taxpayers — about 24.6 million households — paid federal taxes at an effective rate of 4% and shouldered 0.8% of the total tax burden. Meanwhile, the richest 1% of taxpayers — roughly 1.2 million households — paid federal taxes at an effective rate of 29.5%, and shouldered roughly 28.1% of the total federal tax burden. (State income taxes also tend to be progressive, though to a lesser degree than federal taxation and to varying degrees in different states.)

Whether the progressivity of the federal tax code is excessive depends on what one considers an appropriate degree of burden-sharing — a question that is of course not purely economic. But no one can deny that the burden of taxation today is highly uneven across income groups, and that our tax system is therefore highly redistributive (especially since roughly half of federal revenues are used to pay for anti-poverty programs that provide additional support to low earners).

Beyond anti-poverty spending and progressive taxation, the federal government also intervenes in specific markets with the implicit or explicit goal of shifting income toward poorer segments of the population. These interventions include (among others) special protections for unions, limits on prescription-drug prices in Medicaid, agricultural subsidies, trade protections, and mortgage guarantees and subsidies. In each case, the policy in question undoubtedly harms economic productivity rather than improving it: Union protections, for instance, artificially raise the cost of skilled labor; limits on drug prices discourage research and development on new procedures and medicines; farm subsidies reduce agricultural production and increase food prices; trade protections distort the decisions of domestic producers and consumers; and mortgage subsidies lead to over-investment in housing and, as we have learned all too painfully in recent years, can result in dangerous bubbles. The interventions are nevertheless justified with claims that they promote "fairer" prices or other positive outcomes for low-income participants in the relevant markets.

These three pillars of our system of redistribution are not equally problematic. But to understand which are more justifiable and which less so, we must first ask why our government redistributes income at all — and why the public, on the whole, believes that it should.

The first common argument for anti-poverty spending is that the alleviation of poverty is what economists call a "public good" — something everyone would like to see provided, but which few people provide voluntarily because they hope others will do it for them. According to this view, private charity alone would reduce poverty less than everyone would like; only government can address this under-provision, by levying taxes on the non-poor and making transfers to the poor. The poor benefit from such government policy because they receive a higher standard of living, and wealthier people benefit because they value helping the poor more than they resent their higher taxes (for reasons of sheer compassion, or because they believe that helping the poor is a way to achieve other desired ends, like reducing crime). As far as the "public good" advocates are concerned, government redistribution leaves everyone better off.

A second argument for anti-poverty spending holds that private markets do not allow people to insure themselves against the misfortune of being born into poverty. None of us can choose the circumstances into which we are born, but if we were to develop a society that took account of this uncertainty (and so was constructed behind a "veil of ignorance," to borrow the language of the late Harvard political philosopher John Rawls), most people would design it in a way that allowed them to purchase some kind of insurance against poverty. They would, in other words, accept the obligation of paying higher taxes if they were to end up rich in exchange for protection against being left thoroughly destitute were they to end up poor.

Private markets do not provide this "income insurance" because the people who might benefit from it are generally not able (or not motivated) to demand it in advance. Those not yet born, of course, are not around to demand it; their parents could buy the insurance, but the parents whose children would need it most are too poor to afford it. And markets might not even supply this insurance — because insurers would fear that their product would be purchased disproportionately by parents who know, for some reason, that their children will end up poor (much as health insurers either deny coverage, or charge significantly higher rates, to people with costly pre-existing medical conditions). Young workers who might someday benefit from such protection, meanwhile, are often not aware of the risk until it is too late. The conditions simply do not exist for a real market in private anti-poverty insurance to emerge.

Government, however, can address this problem by compelling everyone to participate in social insurance. The "premium" payments consist of the requisite taxes; the payouts consist of welfare benefits distributed to those "enrollees" who end up with low incomes. The imposition of social insurance would not necessarily raise everyone's welfare; people with minimal prospects of ending up poor might regard such insurance as all cost and no benefit. By and large, though, many who are not born poor — as well as those who are — would benefit from this policy.

The third argument for redistribution (which combines some elements of the first two) is a moral one. It asserts that helping the poor is simply the right thing to do. This view assumes that differences in income are driven mostly by luck rather than by effort. And it presumes that the poor benefit more from receiving wealth transfers than the non-poor suffer from paying for the transfers — such that redistribution is a net good for society as a whole.

Each of these arguments for anti-poverty spending may be reasonable as far as it goes, but that alone is not enough to justify such spending. While these perspectives suggest that anti-poverty programs can generate benefits, any responsible evaluation must balance these benefits against the programs' costs. A thorough assessment of redistribution, then, requires a serious examination of the negative consequences of our anti-poverty efforts. And a look at the way redistribution generally plays out in America today indicates that those downsides can be significant indeed.

COSTS AND BENEFITS

In looking at the drawbacks of anti-poverty programs, it is important to consider both the direct costs and the less tangible, but still potentially serious, indirect costs. One of the chief direct costs is the way anti-poverty spending alters incentives: Such programs reduce the reasons for potential recipients of income transfers to work and save, because the availability of aid — and particularly of aid that is available only as long as one remains below a certain level of income — can discourage people from striving to rise above that income level. On the other side of the ledger, the taxation required to pay for anti-poverty programs discourages effort and savings by those who pay for the transfers. People are less inclined to work hard when they know that a large portion of the income they generate will go not to them or to their families, but rather to total strangers.

Whether these effects on economic productivity are large depends on the generosity of the anti-poverty spending, as well as on the magnitude of the taxes required to pay for it. A promise of subsistence income will induce only a few people to live off the dole, while a more substantial guarantee will cause many to reduce their efforts to support themselves. Likewise, the distortions caused by the taxation required to pay for anti-poverty programs increase with the amount of anti-poverty spending, such that a small program will have only small effects on taxpayers' work and saving.

As we have seen above, however, American anti-poverty programs are rather generous. If the $1.45 trillion in direct anti-poverty spending in 2007 had been simply divided up among the poorest 20% of the population, it would have provided an annual guaranteed income that year of more than $62,000 per household — a decidedly middle-class living. The actual distribution of the money is of course less direct; overhead, waste, and other inefficiencies are intrinsic to the operation of these government programs. Moreover, much of the redistribution goes to middle-class families, so the poor are not really provided with a middle-class income. Even so, the support they do receive is substantial. It is hard to believe, therefore, that this generosity — and the tax burden imposed on the rest of the population to pay for it — does not reduce effort among the poor and everyone else, as abundant evidence confirms.

Anti-poverty spending has more subtle downsides, too. Income support for the poor generates envy and demand for transfers from the near-poor. This effect can be seen in programs that have expanded eligibility requirements to well above the poverty line, such as Medicaid in many states, along with the new federal health-care law. The result is further disincentive for effort at the margins of poverty, and additional burdensome taxation beyond. Anti-poverty programs also promote the view that low income is someone else's fault — a notion that, once enshrined in public policy, can reduce many people's work ethic, initiative, and self-reliance. Rather than devoting themselves to increasing innovation and productivity, people throw their energies into chasing government transfers.

Moreover, anti-poverty programs lend credence to the claim that most people will not share their resources unless government compels them to. The evidence of daily life in America, however, shows that assumption to be false. Private efforts to alleviate poverty are enormous: Religious institutions operate soup kitchens; the Boy Scouts organize food drives; the Salvation Army raises money for the poor; Habitat for Humanity builds homes; and doctors' associations provide free health care. In 2009, Americans gave more than $300 billion to charity, a figure made all the more striking by the deep recession. More than 60 million people volunteered, donating some 8 billion hours of work — much of it in efforts aimed at helping the poor. Government charity, moreover, may crowd out private charity: Work by Massachusetts Institute of Technology economist Jonathan Gruber, for example, shows that New Deal welfare expenditures reduced charitable spending by churches.

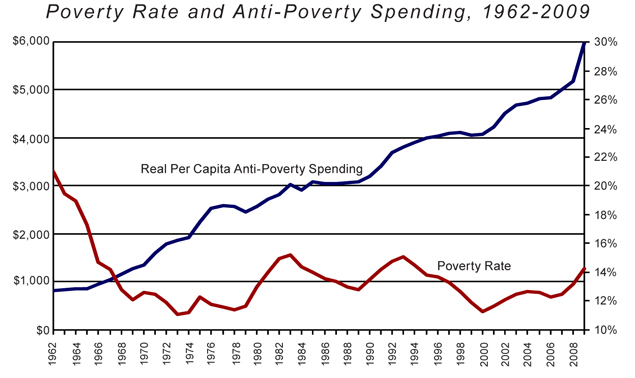

Finally, and perhaps most important, anti-poverty programs have not obviously reduced poverty in recent decades. The following graph shows the poverty rate in the United States (i.e., the percentage of the population living at or below the poverty level) between 1962 and 2009, along with per capita federal spending on the direct anti-poverty programs discussed above (i.e., those that added up to $1.45 trillion in 2007), adjusted for both population growth and inflation.

The poverty rate declined significantly between 1959 and 1964 as the overall economy grew, but this was before the launch of President Lyndon Johnson's War on Poverty (and therefore before the enactment of Medicaid and Medicare, two of the largest anti-poverty programs in existence today). Between 1966 and 2009, the poverty rate fluctuated with the business cycle but showed little downward trend, even as anti-poverty spending grew by a factor of six in real terms. In other words, our anti-poverty programs have been implemented at enormous and ever-increasing cost — and it is not clear that they have done much to reduce the rate of poverty.

The arguments for redistribution are even weaker when it comes to progressive taxation. This is because such taxation redistributes income not only from the rich to the poor, but also among the non-poor. And unlike the social, cultural, and economic divisions that keep the seriously poor locked in poverty for generations, differences in income among the non-poor tend to reflect a variety of personal decisions — such as education, effort, risk-taking, and leisure. Likewise, households in the middle and upper parts of the income distribution have reasonable opportunities to insure against job loss or adverse health events through savings, help from family, working spouses, and other means; generally, they can make it just fine without government's compelling other citizens to pay for their welfare. As a result, the reasons used to justify redistribution from the rich to the poor — i.e., altruism toward people who are needy through little fault of their own, or the need to insure against low income — do not apply when it comes to redistribution among the non-poor.

Redistribution across the income spectrum — instead of simply from rich to poor — also exacts much higher costs. Beyond the fact that providing benefits to middle-class Americans is not a sensible goal of anti-poverty policy, the greater amount of redistribution that it involves requires vastly increased taxation. Progressive tax schemes, moreover, bring about significant economic distortions and inefficiencies because they impose the highest rates on upper-income households, and these households have the most flexibility to shift their energies away from work that generates income (and thus tax revenue), or to channel their savings to tax-preferred investments. They are also, incidentally, the households most likely to generate employment, hiring others to work as nannies, housekeepers, gardeners, and the like. By taking away such a vast amount of their income in order to give more money to the non-poor, such redistributive tax schemes arguably prevent hiring that would allow many of the legitimately poor to improve their condition through paid work.

The redistribution among the non-poor that progressive taxation aims to achieve thus lacks any convincing justification. But it does have substantial costs. Unfortunately, no perfect dividing line exists between redistribution to alleviate genuine poverty and this broader type of redistribution. But policymakers can nevertheless strive to enforce a distinction in general, and to limit attempts at redistribution to those efforts that explicitly help the poor (perhaps by, say, means-testing entitlement programs).

In the case of interventions aimed at tilting outcomes in specific markets toward people with lower incomes, the problems that arise are even more immense than those that result from direct anti-poverty spending or progressive taxation. These interventions generally produce ambiguous (at best) effects on the distribution of income, but they most decidedly distort economic incentives. Minimum-wage laws, for instance, mean higher incomes for some workers but zero income for others, since the minimum wage reduces employment. (A 2008 survey by economists David Neumark and William Wascher confirms this effect especially for the least skilled workers.) Mandated minimum wages that are well above market wages also drive businesses overseas or underground, leading to large reductions in employment opportunities for less-skilled laborers. The minimum wage also distorts firms' decisions about cost efficiency: Seeking more value for their dollars, business managers and owners decide instead to spend their money on capital investments or higher-skilled workers. Minimum wages are thus a good example of how redistributive market interventions are often poorly targeted, and of how they reduce economic productivity.

Other examples abound. Price controls on pharmaceuticals at first appear to be compassionate; in the short term, they can help low-income households afford medicine. In the long run, however, price controls reduce the incentive for drug makers to innovate (and deprive them of capital to invest in research and development). The result is fewer new medications, yielding fewer health-care options for everyone, rich and poor.

Rent controls lower housing costs for those lucky enough to obtain covered apartments, but such controls reduce the supply of rental housing for everyone else. The beneficiaries often include people with good connections or the time to search for controlled apartments, or those whom landlords think will be good tenants (as in the case of Harlem congressman Charles Rangel, who secured no fewer than four rent-controlled apartments in the same luxury building). Many of these people have higher, rather than lower, incomes, so the redistribution involved is partially perverse. (Even in cases where building managers are required to reserve a certain portion of their units for people below a certain income level, these apartments will often be rented out to the temporarily poor — recent graduates of elite universities, say — rather than to those who genuinely need subsidized housing over the long term.)

Another particularly telling example is government support of mortgage lending. Implicit government guarantees of mortgages — through purchases by Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, as well as other policies — encourage lenders to extend loans to riskier and riskier borrowers. Some of these people are poor, but many are not; indeed, the poorest households are not in the housing market at all, as they are almost always renters. And, as noted above, such policies can lead to dangerous market instability — as well as to bubbles like the one that set off the current recession.

Regardless of what one thinks of direct anti-poverty spending, then, one should certainly be critical of progressive taxation and market interventions as ways to help the poor. These approaches have fewer convincing arguments in their favor — indeed, no good arguments at all — and they impose substantially greater costs. Government attempts at redistribution to help the poor should therefore consist, at most, of direct transfer programs. And these programs should obviously be far better configured than the ones we have today.

AN ALTERNATIVE APPROACH

So how should they be designed? Ideally, to maximize the amount of help available to the poor while minimizing the costs to the larger economy. Anti-poverty spending should therefore involve one simple and explicitly redistributionist program: We should repeal all of our existing anti-poverty programs — TANF, food stamps, housing allowances, energy subsidies, mortgage guarantees, Social Security, Medicare, and so on — and replace them with a so-called "negative income tax."

A negative income tax — an idea advocated by Nobel prize-winning economist Milton Friedman — would have two key components: a minimum, guaranteed level of income, and a flat tax rate that is applied to the total amount of income (if any) that a person earns. The net tax owed by any taxpayer would equal his gross tax liability — that is, his earned income multiplied by the tax rate — minus the guaranteed minimum income. If the gross liability were to exceed the guaranteed minimum, the taxpayer would owe the difference. If the gross liability were to fall short of the guaranteed minimum, the government would pay the difference to the taxpayer.

To illustrate, consider a negative tax-rate structure under which the guaranteed minimum is $5,000 and the tax rate is 10%. In this situation, a person earning no income would get a transfer from the government of $5,000 and have a total income of $5,000. A person earning $100,000 would have a gross tax liability of $10,000 and a net tax liability of $5,000, for a total after-tax income of $95,000. A person earning $10,000 of income would have a gross liability of $1,000 and a net liability of negative $4,000 (that is, this person would get a check from the government for $4,000), for a total after-tax income of $14,000.

This proposal — replacing all anti-poverty programs with a negative income tax — has some crucial advantages over the existing hodgepodge of anti-poverty programs. First, the administrative costs of running one simple program would be far lower than the costs of running many complicated programs. Separate taxes to fund Social Security and Medicare would not exist; employers would not have to withhold these taxes and send them to the government. More broadly, the rules and incentives faced by potential welfare recipients would be clear and understandable, compared to the dizzying array of rules that must be navigated by people attempting to collect anti-poverty benefits today.

Second, the amount of redistribution would be totally transparent. Anyone could figure out exactly how much any individual would pay for or receive in benefits. This would be a major change from today's circumstances, under which one must aggregate over multiple programs and convert in-kind transfers to cash equivalents in order to gauge the magnitude of redistribution. Under a negative income tax, it would be easier to tell precisely how much redistribution the government engages in.

Because of this transparency, the negative income tax would likely transfer substantially less income than the panoply of existing programs — which would certainly drive opposition to the negative income tax. Advocates of anti-poverty spending would fear, with good reason, that if the amount of anti-poverty spending were obvious, society would vote for less of it. Likewise, they would worry that if redistribution were undertaken only for the benefit of the poor, middle- and upper-income voters would endorse less of it. That may well be true — but no one who believes in democracy can reasonably argue that our anti-poverty policies should be based on a grand deception of the voting public. (Anti-poverty advocates might also consider that much of what people object to in terms of today's anti-poverty spending is fraud, waste, mismanagement, and other inefficiency; the transparency provided by a negative income tax could alleviate a great deal of this opposition.)

One legitimate concern about the negative income tax is its effect on incentives to work and save. A substantial amount of anti-poverty spending today takes the form of Social Security and Medicare — benefits that recipients get once they turn 65, almost regardless of how hard they have worked or how much they have saved. Earning more and saving more therefore does not result in lower payments. The negative income tax, by contrast, would punish earnings and savings to some degree; converting Social Security and Medicare into a negative income tax, then, would create some disincentives to work and save, especially at the margins of poverty.

Even so, the negative income tax might still introduce less distortion and inefficiency than our existing array of anti-poverty programs, because these programs often incorporate much higher (implicit) tax rates on income. In other words, the various transfer programs we operate today sometimes take away so much in benefits when a recipient's income increases that the recipient is only slightly better off — or, in a few cases, is actually worse off — for getting a job or working more hours. For example, increasing income beyond a certain level can mean complete loss of Medicaid benefits, which can amount to thousands of dollars. Under the negative income tax, though, there is no point at which government benefits disappear all at once; transfer payments phase out gradually with each dollar of income earned, so that the marginal work disincentive would be modest.

It is difficult, therefore, to determine the exact net impact on incentives of a negative income tax versus our current system, holding the amount of anti-poverty spending constant. Overall, however, a negative income tax is likely to produce far less total spending, and thus lesser and fewer economic distortions. Compared to the system we have today, that would be a major change for the better.

TWO EXCEPTIONS

The notion of replacing our existing anti-poverty spending with a negative income tax has one additional implication that merits discussion: Under this approach, all anti-poverty benefits would take the form of cash. This would differ from today's benefits, which come in the form of specific goods (as occurs with Medicaid, school lunches, and government housing projects) or of spending power constrained to specific goods (as occurs with food stamps, Section 8 housing vouchers, and loans for education).

The benefit of transferring cash is that it gives recipients maximum flexibility to decide how they will spend the money they receive. This flexibility is valuable because the right mix of spending will be different for every recipient and every poor family. Some people will decide that their highest priority is a good school for their children; others will decide they need to spend money on transportation to a job; still others will spend their money on medical care, and so on. Assuming reasonable spending decisions, cash benefits maximize the improvement in recipients' well-being for any given amount of income transferred. In-kind transfers, by contrast, force recipients to "purchase" not only a particular kind of good but also a specific "brand" of good — for instance, a residence in a particular housing project, or health care at a specific hospital that serves Medicaid patients. The result is severe limitations on poor people's options and independence.

One possible objection to cash transfers is that some recipients might make bad spending decisions. A common concern is that poor people will spend their cash transfers on alcohol, drugs, or gambling. Forcing recipients to use their benefits to procure basic necessities, the argument goes, might thus increase poor people's welfare, especially that of poor children.

Such fundamentally paternalistic concerns are surely overstated. Relatively few parents, for example, deprive their children of food, shelter, and clothing, no matter how dire their own circumstances. But paternalistic concerns are not entirely unfounded, and in any case they carry great weight with the general public.

The best way to address such concerns in a system of cash transfers is through vouchers. Although these can be redeemed only for broad categories of goods — such as food, education, or housing — recipients still retain a great deal of flexibility regarding the exact purchases they make and the vendors from whom they choose to make those purchases. Housing vouchers, for example, force recipients to spend their transfer funds on housing; the money the vouchers provide, however, can be used in any neighborhood, not just at a government housing project in an inner-city slum. Vouchers are also preferable to the direct provision of goods by government because they leave production to the private sector, which is typically more efficient. At the same time, vouchers pose little risk of serious misuse: One can spend an education voucher on a mediocre school, but one cannot easily gamble it away at the race track.

A second possible objection to the cash-only approach is that the markets for some goods might work badly on their own, such that direct provision of these goods by the government is the only way to supply them at low cost to poor people. The standard example invoked in this argument is health insurance. A considerable body of economic analysis claims that private health-insurance markets do not operate well because of adverse selection — the tendency of people with worse health to be more likely to buy insurance. But these concerns, too, miss the point. Private insurers can readily identify who is healthy (or not), and, equipped with this knowledge, they would happily insure everyone they could, as long as they could charge appropriate premiums. The problem is that such premiums — the especially high ones for sick customers — would price some people out of the market. Thus the main justification for subsidizing health care is not fixing a market inefficiency, but redistribution. And indeed, the direct provision of health insurance by the government is one of the major sources of inefficiency — and therefore high costs — in our health-care system today, as the expenses of Medicare and Medicaid spiral out of control.

But while concerns about a dysfunctional health-insurance marketplace may be excessive, they are not entirely misplaced. When it comes to health care — more than any other good the government might provide to the poor — there may be an argument for some direct provision of insurance, rather than simply the money to purchase it. Means-tested health-insurance vouchers can guarantee the poor a minimal amount of health insurance with relatively few adverse effects on the health-care marketplace.

The ideal system of redistribution to benefit the poor in America, then, would involve mainly cash transfers. Possible exceptions might include vouchers for education and health insurance.

Where possible, these exceptions should be managed at the state level; to the extent that the federal government is involved, it should supply funding to the states through block grants — which provide a set amount of money to the states, generally based on each state's population, and allow the states to make their own decisions about how to allocate the funds. This, in turn, allows more decisions about benefit allocation to be made by people closer to the ground — people who have a better understanding of the lives and needs of benefit recipients. It also gives the states more flexibility to experiment with different approaches.

Indeed, the negative income-tax system as a whole might well work best at the state level — that is, if it replaced both federal and state redistribution efforts with 50 state-level negative income-tax systems. Advocates of redistribution fear that state-level negative income taxes would start a "race to the bottom," in which states slash benefits to avoid attracting poor populations. But in fact, numerous examples — including minimum-wage laws, TANF and Medicaid provision, and pre-1935 state-level Social Security programs — show that states can exhibit substantial altruism, so that state-level anti-poverty efforts would not be miserly. Concern over in-migration might nevertheless counter political pressures in favor of excessive expansion, yielding a better balance than a federal system could attain. And state experimentation would no doubt produce some innovations and improvements that a federal system would fail to discover. Of course, a transition from our current system to a negative income tax might be easier if it first involved a transition to one federal negative income tax. In an ideal world, however, such a system would eventually be turned over to the states.

A MORE RATIONAL SAFETY NET

Moving from the complex and cumbersome redistributive anti-poverty scheme we have today to the one proposed above would be a truly radical reform. A system in which government would eschew intervention in specific markets, abandon progressive taxation, combine nearly all existing anti-poverty programs into a negative income tax, and assign as much of the remaining work of redistribution as possible to the states could come about only through a dramatic shift in our thinking about anti-poverty policy. And such shifts never come easily.

Still, the goals in question — helping people who are truly in need, while also not weakening the broader economy — are so important, and so poorly served by today's anti-poverty programs, that they simply demand such a change. Of course, an anti-poverty policy that met these two criteria might still be far from perfect: Even a minimalist negative income tax would have some distorting effects. Keeping such a policy minimal, moreover, would be a constant struggle. Still, this approach would certainly be an improvement on our existing array of anti-poverty tools. It would be better designed to advance the goals shared by much of the public; it would also avoid the immense costs and dangerous pitfalls that, too often, have accompanied America's anti-poverty efforts over the past half-century.

Most of all, the discussion surrounding these proposals would force Americans to carefully consider some important issues we have ignored for far too long: the justice of redistribution, the wisdom and effectiveness of the methods through which we pursue it, and whether those methods have met any reasonable empirical standards of success. Given how much of our citizens' resources, and our nation's politics, are consumed by these questions, the least we can do is devote some serious attention to them — and, in the process, perhaps finally embrace an anti-poverty strategy that makes sense.