Religion and the Marriage Problem

In one of James Q. Wilson's last and finest debate performances, he defended the criminalization of hard drugs before a rapt audience in San Francisco. That evening, Wilson told the many drug enthusiasts in attendance that all Western democracies must remain situated between the philosophies of Locke and Aristotle. That is, decent democracies must find a way to balance the ideals of liberty and virtue, freedom and morality. The theme of ordered liberty was important to Wilson. It permeated his writings on crime, character, and marriage. And as the many hostile questions Wilson fielded that evening must have reminded him, the libertarian currents in our culture are quite powerful.

Wilson, of course, was hardly the first scholar to be preoccupied with the special dangers of self-indulgence in democracies. Alexis de Tocqueville, another great student of American democracy, shared Wilson's worries. But unlike Wilson, Tocqueville regarded religion as an essential bulwark against American egoism. Tocqueville, in fact, was "firmly persuaded that at all costs Christianity must be maintained among the new democracies." Wilson, meanwhile, did not have much to say about religion, a fact that may seem surprising given both the breadth of his writings and his deep interest in civic virtue. Aside from occasional short essays, speeches, and passing commentary in his many books, Wilson ignored the subject of religion. There are only a few brief discussions of religion, for example, in The Marriage Problem, On Character, and Crime and Human Nature. And in The Moral Sense, Wilson looked to the biological sciences, not theology, to understand our moral nature.

Why was Wilson, a scholar who described himself as "seriously interested in the problem of character," so silent on the subject of American religion? One possible answer is that, like so many secular intellectuals, he was attracted to other topics. Wilson himself noted the tendency of academics to neglect faith. "This is a matter to which scholars have given relatively little attention," he observed, "because scholars, especially in the humanities and the social sciences, are disproportionately drawn from the ranks of people who are indifferent — or even hostile — to religion." Wilson was never hostile to religion, of course. But unlike Tocqueville, Wilson did not regard religion as necessary to order moral life in democracies. He pointed out that Japan, for example, enjoyed low rates of crime and drug abuse despite its pervasive secularism. One might add that the same irreligious yet decent citizens can be found in the Scandinavian nations, as sociologist Phil Zuckerman recently emphasized. And even in religious nations, Wilson observed that there are many moral citizens who do not receive communion or become born again. From these observations he concluded that religion is not the true "source of morality." Following Aristotle, Wilson believed that moral virtue develops primarily through a process of habituation, not through religious conviction or philosophical wisdom.

Thus, Wilson believed that human character could be improved even in the most secular societies. And in a nation with the most churches per capita, Wilson made a name for himself developing successful remedies to social problems that did not tap the considerable resources of America's many religious communities, especially in the case of crime. He attributed the dramatic decline of crime in New York City, for example, partly to the adoption of the "broken windows" theory, a novel approach to policing that he developed with George Kelling.

Not all the social problems Wilson addressed, however, have been as responsive to policy changes as urban crime. The marriage problem in particular has proven to be far more chronic and intractable. While violent crime has dropped precipitously since 1994, American family life continues to weaken. Currently only about half of American adults are married, down from nearly 75% in 1960. This is partly because Americans are becoming more likely to choose cohabitation — an even more unstable arrangement — than marriage. Some commentators were encouraged by the apparent stabilization of divorce rates in recent years after decades of increases. But a new and influential study by Sheela Kennedy and Steven Ruggles found that "overall divorce incidence has increased substantially in recent years."

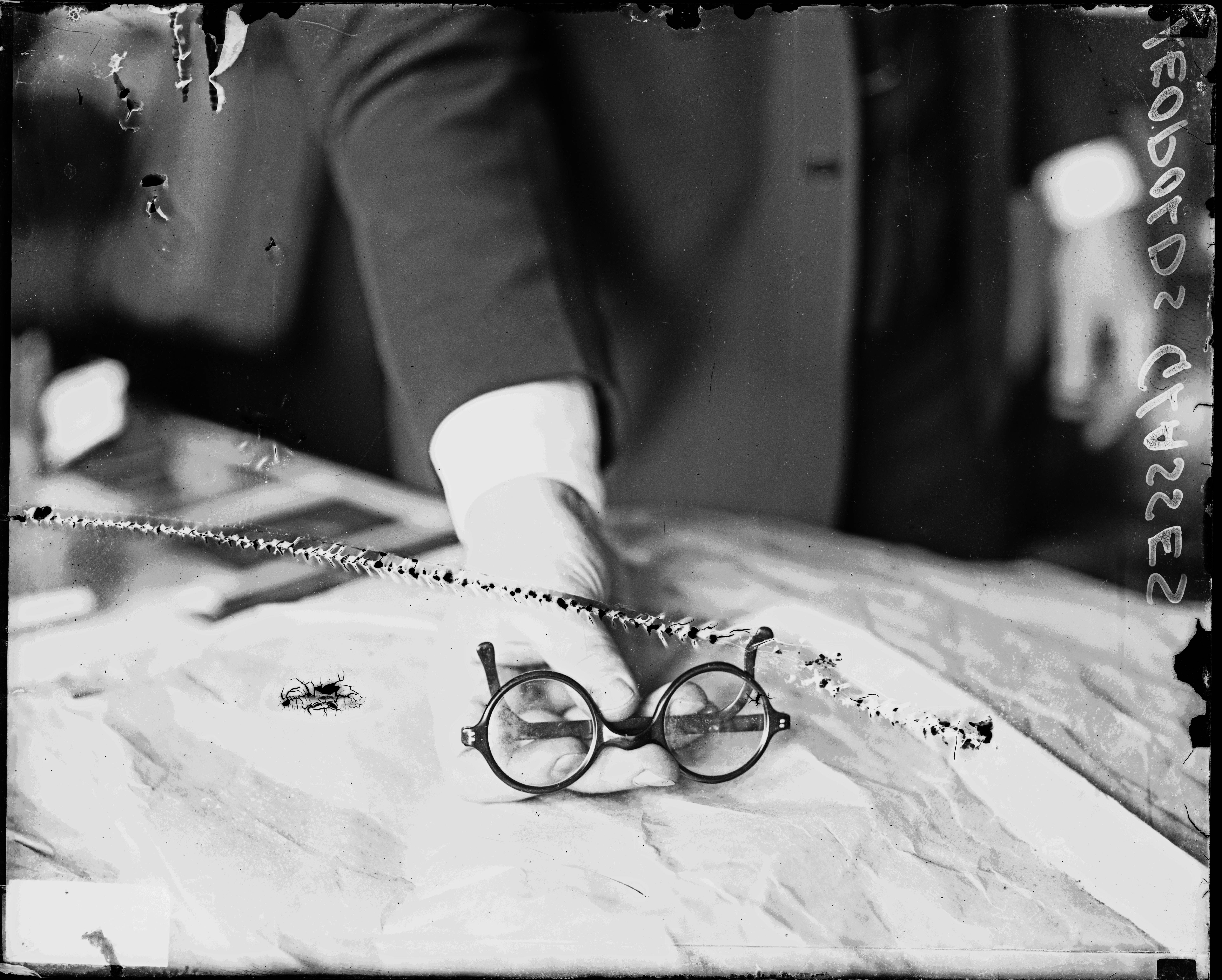

Wilson, of course, was at the forefront of drawing attention to the marriage problem, especially its troubling class dimensions. A decade before Charles Murray's Coming Apart sensitized many elites to the deepening chaos that plagues millions of poor and working-class families, Wilson argued that American families were culturally separated into "two nations," a claim that Mary Eberstadt recently revisited in these pages. But though one might suspect that Wilson's interest in the marriage crisis would have drawn him deeply into the subject of religion — especially since it has long provided the cultural foundation for marriage in America — he never pursued it. This might be because he correctly saw evidence of religion's weakness in the face of marital breakdown.

American religion failed to curb the decline in marriage, in Wilson's view, not because it was necessarily weak by nature. To the contrary, Wilson admired the ability of Protestant reformers to create organizations that reduced crime and alcohol consumption during the 19th century. Religion is far less powerful today, he suggested, because it has been abandoned by the very elites who are essential to bringing about dramatic cultural change. For Wilson, major cultural changes tend to move from the top down, not the other way around. And ever since elites abandoned a Christianity that embodied an "ethos of self-control," they have been preaching an "ethos of self-expression." This ethos, in Wilson's view, worked to the detriment of Americans, especially the poor and working class.

But even if America could return to the old religious order, it is not clear Wilson would have welcomed it. Wilson, a conservative scholar greatly concerned with civic virtue, admired the practice of self-restraint, but he was far less enamored of the de facto Protestant establishment that made it possible in the 19th century. Wilson, therefore, was quietly a greater fan of post-1960s America than his progressive critics or right-wing admirers sometimes appreciated. In this respect, Wilson embodied the very tension between Locke and Aristotle that he thought was so essential to any decent democracy.

Despite Wilson's reservations about the desirability and prospects of another Great Awakening, in the end he could not escape the sense that religion had to be part of a stronger marriage culture. Unlike controlling crime, which could be reduced through innovative policies, the restoration of marriage required deeper cultural change — with substantial help from religion. Wilson's analysis of the marriage problem, therefore, resulted in a daunting conclusion: If we hope to rebuild marriage among poor and working-class citizens, there may not be any good substitutes for the sort of religious revivals that galvanized Americans in the 19th century.

TOLERATING DIVORCE

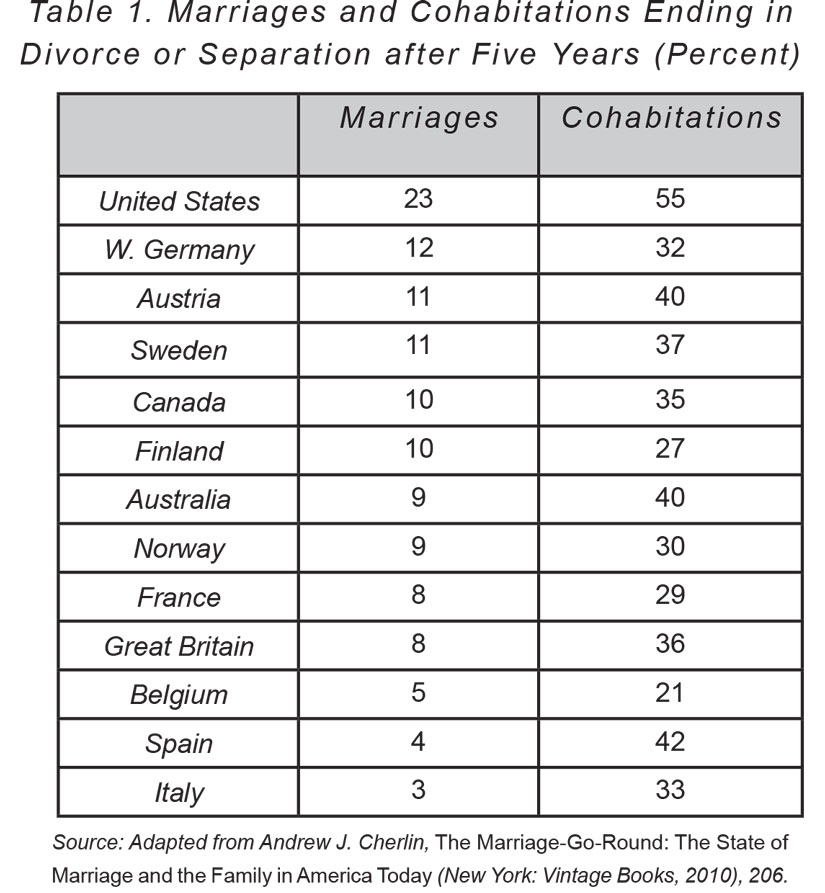

One aspect of the marriage problem Wilson did not seem to appreciate is just how accommodating Christianity itself has become to our new marriage culture. He failed to see, much less investigate, an important paradox: America is among the most religious Western nations, as well as the most prone to divorce. In fact, in no other Western democracy do citizens move in and out of marriage more frequently than Americans do. Americans are at least twice as likely to divorce as Germans, Swedes, Fins, or Canadians, all peoples with high divorce rates by Western standards, as shown in the table below. It is true that citizens of other Western nations cohabitate more frequently, and that such arrangements are generally less stable than marriages. But cohabitation is also a much more stable partnership in other democracies than it is in the United States. Thus, Americans move in and out of relationships more frequently than citizens in other democracies do, often dragging their troubled children with them.

Historical evidence suggests that Americans have always been more tolerant of divorce. As sociologist Andrew Cherlin explains in his book The Marriage-Go-Round: The State of Marriage and the Family in America Today, "It is likely that the chance of a marriage ending in divorce has always been higher in the United States than in most of Europe." With certainty, however, we know that divorce was far more common in the New England colonies than in Great Britain, a trend that continued into the 20th century. By the 1900s, in fact, a "hundred times as many divorces occurred in the United States," even though America's population was just twice that of Britain's.

Some scholars contend that American consumerism is responsible for the nation's higher divorce rates; it corrupts the habits of citizens, they argue, by stirring appetites for novelty that can never be sated. Tocqueville pointed to a similar cultural malady when he argued that Americans' taste for petty physical comforts cultivated a deeper restlessness. Americans, Tocqueville wrote, "never stop thinking of the good things they have not got." He added, "They clutch everything but hold nothing fast, and so lose grip as they hurry after some new delight." A related yet distinct thesis says that, as Americans move frequently for new job opportunities, they constantly disrupt the social ties that tend to stabilize family life.

Others believe that America's exceptionally unstable family life is rooted in its political creed, which is embodied in the Declaration of Independence's emphasis on consent and right to revolution. Divorce and political revolution represent the right of an individual to exit a union that no longer serves its proper ends. The link seemed apparent to Thomas Paine, who advocated for both political revolution and the necessity of more lenient divorce laws. After his second marriage fell apart, Paine reflected on the problem of unhappy marriages. When "love is gone" from marriage, Paine lamented in Pennsylvania Magazine, "the repose of all their future days are sacrificed."

There are almost certainly powerful and complex links between America's political ideals, consumerism, and modern marriage culture. But these forces do not seem to fully account for the American colonies' relative tolerance of divorce. As the foregoing discussion made clear, Americans' tolerance for divorce was evident long before modern consumer economies developed, and even before the American Revolution. Nor do our political ideals and consumerism seem to fully account for our exceptional marriage culture today. The consumerist culture and philosophical heritage of Britain, after all, is comparatively more like America's than any other Western democracy. Nonetheless, Britain's divorce rate is average by European standards.

Perhaps the most significant early difference between America and Britain was a religious one. Cherlin attributes the relative intolerance toward divorce in Britain to the enduring influence of Catholic doctrines. In the American colonies, meanwhile, citizens "allowed divorce on the bases of adultery and desertion, following the teachings of Luther and Calvin." Cherlin believes that this early American experience with divorce was formative.

It is unclear whether America's early experience with divorce was as significant as Cherlin seems to suggest. Divorce, after all, was still harshly stigmatized in the colonies and rare by contemporary standards. With far more confidence, we can conclude that American colonists' early tolerance of divorce in certain circumstances demonstrated a willingness to accommodate the practice, especially compared to other European nations.

THE SILENT REVOLUTION

Many American states continued to liberalize their divorce laws in the 19th century, even as Protestant reformers often expressed alarm at America's divorce rate. By 1860, for example, a majority of states allowed divorce in cases of chronic drunkenness. As the practice of divorce increased throughout the 20th century, religious protest waned. During that century, a deeper tradition of Protestant accommodation took shape. Political scientist Mark Smith found that divorce "virtually vanished" as a politically contested issue after the 1920s. By the 1960s and '70s, American Protestants did essentially nothing to oppose the revolution in divorce laws. Smith concluded that no-fault divorce laws passed "without much controversy and encountered little to no organized opposition." It was a culture war that never happened. Partly for this reason, political scientist Herbert Jacob called the rise of no-fault divorce a silent revolution.

Divorce reforms were also more radical in America than in European democracies, with the exception of Sweden. The new laws in Europe, for example, tended to require much longer waiting periods than those adopted in the American states.

What little opposition to the divorce revolution that did exist in America came from the Catholic hierarchy — again emphasizing the tolerance of American Protestants toward divorce. In New York, for example, Jacob found that the "most formidable and vocal opponent to liberalization of its divorce laws was the Catholic Church." States with large Catholic populations also adopted no-fault divorce later than states with large numbers of Protestants. Unlike the expansion of abortion access and court decisions on school prayer, however, the liberalization of divorce failed to energize the Catholic laity into mass political action. Even William Buckley, Jr.'s National Review devoted a scant three paragraphs to the topic of divorce during the silent revolution. And when Buckley turned momentarily to the subject of divorce, he called the old restrictive laws "antiquated."

It also did not help that the Catholic Church hemorrhaged members during the 1960s and '70s as it suffered from a sharp decline in its own institutional authority. Robert Putnam and David Campbell found that Mass attendance "fell so dramatically that Catholics alone accounted for much of the aggregate decline in religious attendance during the long Sixties." Today, the odds of two Catholics marrying each other are less than would be expected by random chance. Meanwhile, Rome streamlined its annulment process in the wake of the Second Vatican Council, a development that signaled its greater tolerance for divorce in practice, if not theologically.

Mormons constituted a second pocket of quiet resistance to the divorce revolution. Utah waited until 1987 to change its laws, largely because of the powerful influence of Mormonism and its familial culture. Divorce rates for temple marriages also remain very low by American standards. While about 40% to 50% of all first marriages end in divorce, only 10% to 15% of temple marriages do. Mormon marriages are also more stable than those of any other religious group in America, with the possible exception of Muslims.

The reasons for Mormonism's unique marriage culture are varied. But one important theological stance that separates Mormonism from other Christian denominations is its belief in the doctrine of eternal marriage. Under this doctrine, temple marriages last for all eternity in the celestial kingdom to come, in addition to being united in this earthly life. These unions can be undone, but only in certain narrowly defined circumstances and only if accepted by the Mormon Church hierarchy. It is ironic that the most distinctly American religion has resisted our national penchant for divorce far better than our imported faiths.

One might suppose that Protestant evangelicals were silent during the divorce revolution because of their tendency to focus on soul-saving rather than political campaigns. Evangelicals were engaged and organized, however, in protesting the school-prayer and Bible-reading court decisions in the 1960s. Then in the 1970s, they shocked the political establishment by defeating the Equal Rights Amendment. Even after the emergence of more durable Christian Right interest groups in the 1980s, evangelicals targeted our permissive abortion regime — but not marriage laws. Today's Christian Right leaders rarely suggest that divorce laws should be changed, though they do often emphasize the harmful consequences of the divorce revolution. Meanwhile covenant marriage — a type of legal marriage that requires pre-marital counseling and has higher barriers for divorce — has enjoyed only weak support from evangelical churches, and laws promoting it have passed in only three states. In these states, a mere 1% to 3% of the public has opted for covenant marriages.

And despite the pro-family rhetoric of some Christian Right leaders, evangelical ministers keep softening their interpretation of the Bible's apparent prohibition of divorce. Sociologist Brad Wilcox found that pastors in the Southern Baptist Convention (SBC) have relaxed their stance on divorce over the last century. Whereas divorce and remarriage were once strictly forbidden by the SBC except in cases of adultery, only 36% of its pastors embraced this doctrine by 1980. Wilcox found that even the more conservative pastors in the SBC often engage in "elaborate hermeneutical maneuvers" to justify divorce on biblical grounds. Such liberal readings of the New Testament led Wilcox to conclude that "conservative Protestant discourse regarding divorce and remarriage is characterized by a striking level of ambivalence and dissensus — especially considering the fact that divorce poses a more direct threat to familism than either homosexuality or abortion."

Such ambivalence is found even in the independent fundamentalist churches that revolted against the SBC for its perceived theological liberalism. Sociologist James Ault, in a careful ethnography of a fundamentalist Baptist church, found that it had hardly been immune to these liberal currents. Though its pastor would routinely thunder "God hates divorce!" from the pulpit, he would also encourage divorce for parishioners who were in bad but not abusive marriages. And when his own daughter divorced, the pastor's wife responded that "[t]hey were just too young" — just as any secular parent might.

Evangelicals and fundamentalists quietly make allowances for divorce partly because the familial lives of the nominal Protestants and seekers in their social orbit are often quite disordered. This is largely because nominal evangelicals tend to come from lower socioeconomic backgrounds, which has left them vulnerable to the turbulent changes in family life since the 1960s and '70s. Yet the family disorder so evident among the American working class also explains why conservative Protestants are sometimes more troubled by these cultural changes. "The irony," Wilcox explained, "is that one reason that conservative Protestants are talking right on family matters is that they do not like the fact that they have walked left or that their friends, family members, or neighbors have walked left on family matters." Unlike America's Mainline Protestants and secular elites, evangelical ministers and leaders can see the casualties of the divorce revolution in their own families, pews, and neighborhoods. Mainline Protestants, meanwhile, are publicly devoted to less traditional family forms. But they are also more conservative in their behavior and sheltered from the social consequences of the divorce revolution because of their relatively high socioeconomic status.

Even though Christians have tended to accommodate the divorce revolution, religious couples do enjoy somewhat more stable marriages than secular citizens. Wilcox and Elizabeth Williamson estimate that devout Christians are about a third less likely to divorce than unaffiliated Americans. Only Mormons, however, can boast substantially lower rates of divorce than the unaffiliated population. Religious Americans, moreover, look even less pious when they are compared to secular citizens in other European democracies. In fact, some estimates show that the unions of secular Swedes are more stable than the marriages of religious Americans. Secular and religious citizens, therefore, are responsible for America's marriage problem.

RELIGIOUS INDIVIDUALISM

Evangelical Protestants have also "walked left on family matters" because many of them think of the institution of marriage in much the same way that they think of their churches: as voluntary associations that should be maintained as long as they satisfy deeper spiritual and psychological longings. When churches or marriages fail to serve those ends, one is free to simply leave and form a new association. This is partly why evangelical churches have tended not to seek dramatic changes in our marriage laws or culture. To do so would offend their very ethos, which is a kind of expressive individualism that seeks happiness and authenticity in a personal relationship with Jesus Christ.

The seeds of this religious individualism have been present in American Protestantism from the beginning. The revivals of the First Great Awakening, noted historian David Peterson del Mar, "encouraged people to think — and certainly feel — for themselves." But those individualistic tendencies were also controlled, Del Mar added, through the creation of communities that were "austere and interdependent at a time of growing prosperity." Even after Americans elevated the importance of a romantic marriage in the 19th century, aspirations for a love match were held in check by communities governed by traditional religious mores. The New York Female Moral Reform Society, for example, published the names of men that its members judged guilty of sexual immorality.

By the 1960s, however, American Christianity became less focused on maintaining community standards and more centered on the needs of restless seekers. "Across Protestant and Catholic religious life," concludes Andrew Cherlin, "the spirituality of seeking was not about laws or doctrines but about finding a style of spirituality that made you feel good." This change reflected the deeper logic of the divorce revolution as well. Modern marriage, Cherlin observes, "was not about rules and traditions but rather about finding a style of family life that gave you the greatest personal rewards." Thus, both religion and marriage became sites for personal growth. Similarly, Ross Douthat in his book Bad Religion laments that too many strains of modern faith — from the prosperity gospel to "spiritual but not religious" gurus — sanctify our personal appetites. Religion, Douthat concludes, has too often become "an enabler of adult desire, whether gluttonous or libidinous, and a source of endless justification for whatever the heart already prefers to do."

Mormonism highlights the association between stable religious communities and family life. As noted earlier, the divorce rate of observant Mormons is unusually low by American standards. Individualistic sensibilities are also far weaker in their religious communities. The Mormon Church makes greater demands on its members than either Catholics or evangelicals, including abstaining from alcohol, a tithe of 10% on their annual income, and two years of mission work. "Even more so than conservative evangelical Christians," Del Mar observed, "Mormons continually remind one another that they are singular and chosen people."

There is also far more pressure in Mormon communities to remain in the faith. Putnam and Campbell found that Mormon parents are significantly more likely than evangelical or Catholic ones to say that it is "very important" that their children marry someone in their own faith. Mormons seem to respond to these parental pressures, as they are much less likely than evangelicals or Catholics to intermarry. These choices probably strengthen marriage; we know that couples who practice a common faith tend to be happier than those who do not. Mormons are also less likely to lapse into secularism or switch religions than other religious groups. And the stability of Mormon religious identities makes for a steady community life. Cherlin finds that the residents of Utah's towns and cities are much less likely to move than those in other Western states, which provides for deeper "social integration" and discourages divorce.

Even when conservative strains within evangelical Christianity have shown an interest in strengthening marriage, they have gravitated to strategies that emphasize personal, moral suasion — not legal reforms or the stigmatization of those who do not conform. The Promise Keepers initiative, for example, strengthened some male evangelicals' commitment to their wives and children. That movement, stresses historian Margaret Bendroth, "preached a gospel of personal transformation — honoring promises to wives and children, spending more time at home, being a regular churchgoer — not large-scale social change." Bendroth's conclusion is consistent with sociologist Christian Smith's research, which found that "the majority of evangelicals think about dealing with family breakdown primarily in terms of individual — not political or institutional — influence and change." This personal, moral suasion mirrors evangelicals' own faith in that it seeks a "personal conversion of the heart."

Or consider Focus on the Family, an organization often misunderstood by its secular critics. In Colorado Springs, where Focus on the Family is now based, a favorite bumper sticker among liberal motorists reads, "Focus on Your Own Damn Family." Such citizens believe that the Christian Right should privatize its own familial values and certainly not attempt to use the law to reshape American families. It is a sentiment that is widely shared in elite, liberal circles. But such critics tend to overemphasize Christian conservatives' appetite for what is sometimes called "legislating morality." The vast majority of Focus on the Family's resources are reserved for ministering to evangelical families, especially for dispensing parenting advice to stay-at-home moms. Only a small fraction of its resources is spent on political lobbying. Thus, Focus on the Family does in fact focus its energies and considerable wealth on evangelical families, not outsiders.

With the important exception of pro-life organizations, Christian Right leaders have had a difficult time maintaining even the most successful pro-family organizations. Concerned Women for America and the Christian Coalition, for instance, once enjoyed large, active memberships. The Christian Coalition even managed to help mobilize millions of disaffected white evangelicals in the 1990s, which has had an enduring effect on their political participation in elections. But in the last decade these organizations have become empty shells, with little more than Washington-based staffs and websites.

Why have conservative evangelicals and Catholics long shown much more enthusiasm for expanding the rights of the unborn rather than defending marriage, our most important social institution? One possibility is that many Christians have sacralized a certain understanding of the liberal tradition. Like other Americans, Christians are part of a rights-oriented culture. That common culture predisposes Christians to be especially sympathetic to the pro-life movement. But that same liberal tradition also encourages Christians to privatize their other moral views that do not involve fundamental rights claims. This development may be good news for those who worry about a multi-front culture war. But it may not bode well for our troubled marriage culture.

Protestants during the Victorian Era, of course, were far more comfortable meddling in the lives of wayward Americans, partly because of their cultural authority and partly because liberal currents in the larger culture — including the personalization and privatization of religious beliefs — were far weaker. Wilson greatly admired the cultural power wielded by these religious reformers. They managed to reduce illegitimacy and crime in the face of social changes that should have increased them, including urbanization, immigration, and industrialization. But today, Wilson emphasized, the secularized American elite would regard a pro-marriage revivalist as "a figure to be caricatured." Thus, the leadership that might restore a marriage culture, Wilson concluded, is "conspicuous by its absence."

For Wilson, elites were indispensable to cultural change, leading both the religiously inspired movements of the 19th century and the more liberalizing trends in modern-day America. But rather than preach an "ethos of self-control" as they did in the 19th century, elites in the 20th extended the principles of Enlightenment individualism by preaching an "ethos of self-expression," which was especially destructive when it filtered down to the lower classes. "Educated people," Wilson observed in On Character, "are for the most part the product of familial arrangements that have produced in them sufficient self-control and regard for others." But some of the college educated "take for granted their own habitual civility even while deriding its source." As Wilson concluded, "The effect of this attitude on others can be devastating."

Conservative Christians tend to underestimate the cultural significance of what Wilson called the "upper class" when they imagine that America can be remade by a movement from below. Sociologist James Davison Hunter has been especially critical of this tendency in evangelical circles. Hunter finds that the cultural influence of Christianity is "negligible" because it is largely absent from the country's most important culture-making institutions, especially the film industry, advertising, entertainment, media, and arts. But given the hostility of those same cultural centers to both Christianity and conservatism, it is hardly surprising that Christian Right leaders often emphasize the potential cultural power of movements from below.

RESTORING A MARRIAGE CULTURE?

Few social changes in recent decades have been as harmful to children as the rise in divorce, out-of-wedlock childbearing, and fatherless households. Most if not all of the increase in child poverty since the 1960s has been caused by changes in family structure, which is also among the best predictors of variation in urban crime rates and drug abuse. The loss of family stability also accounts for much of the increase in economic inequality since the '60s. As Isabel Sawhill recently put it, "Even some of our biggest social programs, like food stamps, do not reduce child poverty as much as unmarried parenthood has increased it."

Wilson's own analysis suggests one possible remedy to today's marriage problem: another Great Awakening. Yet he also recognized that American elites are too modern and too firmly ensconced in a post-Christian culture to ever be the vanguard of a new revival. He admired programs like Alcoholics Anonymous that helped people transform their lives. But if religion's main moral virtue is that it helps alcoholics and other dysfunctional Americans become respectable citizens, what can it offer to Harvard professors like Wilson and other members of the highly functional elite?

While neoconservatives like Wilson were certainly more sympathetic to religion than other secular intellectuals, they nonetheless struggled to see much point in becoming religious themselves. "Many of us who think religion is useful," Wilson admitted, "think it is useful only for 'other' people." Yes, it might be good for the less fortunate if elites embraced religion, but such a motive will never inspire conversion. Wilson drew a similar conclusion with pointed humor in a Commentary essay that addressed Robert Putnam's contention that churches might cultivate more interracial communities. As Wilson put it, "[Putnam's] third proposal, encouraging outreach by churches, might well make a difference, but how do we go about it? Require people to attend an evangelical church? Would Robert Putnam attend? I suspect not."

Even though the old Protestant establishment was good at ordering moral life, Wilson would not have welcomed its resurrection. As Wilson observed, most of us would not want to return to "all the things that reinforced the familial culture during the nineteenth century." He asked rhetorically: "Would you ignore the Enlightenment, with all that it has meant in terms of economic growth, political freedom, scientific invention, and artistic imagination?" In On Character, Wilson again emphasized that the blessings of the new modern order required the death of the old religious one: "For two centuries we have been enjoying the benefits of having supplanted revelation with reason. Most of us will continue to enjoy those benefits for centuries to come. But some will know only the costs."

Wilson's ambivalence about the old Protestant order should remind us that cultural conservatism tends to be what Samuel Huntington called a "positional" ideology. Unlike socialism or liberalism, which develop more universalistic prescriptions, conservatives seek to preserve and strengthen particular institutions with the tools at hand. Because those same institutions are the products of a unique society and moment, the concerns and remedies of conservatives are always shaped and constrained by a certain historical context. Wilson's ambivalence about the old order should also remind us that he was hardly a paleoconservative trying to rescue America from becoming a modern-day Sodom — even though he never shied away from using unfashionable words like "soul," "virtue," or "evil." Similarly, Wilson did not elevate some political principle far above all others, as libertarians do in the case of liberty or progressives do in the case of equality. Instead, Wilson always believed that modern democracies must find a balance between competing goods, whether they be liberty and virtue, diversity and community, or democracy and rights. As he once put it regarding such tensions, "balance is all."

Finding a balanced and workable remedy to the marriage problem, however, is not so easy, as Wilson well understood. We cannot simply revive some of the salutary features of the old order, graft them onto the new, and then expect this hybrid regime to work as expected. Megan McArdle, for example, argued that if we make divorce more difficult to acquire, it might actually make couples less likely to tie the knot in the first place. Restrictions on divorce in the old regime may have worked only because they were part of an elaborate social system that supported marriage. "The divorce laws of an earlier era," McArdle observed, "were one part of a complex social institution with mutually reinforcing norms and a fairly elaborate system of punishments and rewards." McArdle especially emphasized the "energy society spent encouraging people to get married in the first place — not just with the gauzy dreams of wedding gowns...but also with a complicated system of carrots and sticks that have now completely vanished." As someone who was always concerned with the unintended consequences of policy proposals, it is a point Wilson would have appreciated.

A successful remedy to our marriage crisis, therefore, would need to acknowledge these contemporary circumstances and seek to work inside the very individualistic culture that has shaped the sensibilities of secular and religious Americans. One way of doing so is to mimic the anti-smoking campaign by promoting the health benefits of marriage. As Linda Waite and Maggie Gallagher have shown, marriage makes us happier, wealthier, and healthier. It does so because marriage is a complex social institution rather than simply a partnership between two individuals. The health effects of marriage are especially large for single men, a population that particularly troubled Wilson. In fact, being unmarried chops nearly a decade off a man's life on average. "Being unmarried," Waite and Gallagher conclude, "can actually be a greater risk to one's life than having heart disease or cancer." Meanwhile, divorce often harms children without improving the happiness of adults. One study, for example, found that some 86% of unhappily married couples who remained together were happier five years later. Such a campaign, therefore, would argue that marriage is a public-health issue, rather than a moral one. It would preach an ethos of self-restraint, but also tie that very restraint to our own health, not religious obligations.

A pro-marriage campaign, however, would have the least appeal among poor and working-class Americans — precisely those citizens who need to heed its message most. This is what happened with the anti-smoking campaign, which reduced nicotine consumption dramatically among those with high socioeconomic status while barely denting its use among the poor. Between 1965 and 1999, families in the highest income bracket reduced their smoking by 62%, while those in the poorest bracket decreased their use by just 9%. Moreover, this moderate decline among poor citizens seems to be largely due to increased taxation, not a progressive health campaign. Declines in smoking among less-advantaged Americans have also stagnated, a development that has increased the class divide in nicotine consumption. Today in places like Clay County, Kentucky, a staggering four in 10 citizens smoke, while only one in 10 residents enjoy lighting up in the wealthy suburbs that surround Washington, D.C.

Why did some poor and working-class citizens quit smoking in the face of price increases but remain unmoved by the many voices that promised an untimely death for lifelong smokers? Lower-income citizens are situated in a culture that is present-oriented, and it is this narrower time horizon that sensitizes them to the immediate cost of a carton rather than the long-term likelihood of a premature death. As Wilson's mentor, Edward Banfield, emphasized decades ago, one's "time horizon" is largely a "function of his class culture alone." Compared to a middle-class American, Banfield observed, the working-class man "is little disposed toward either self-improvement or self-expression; 'getting ahead' and 'enlarging one's horizon' have relatively little attraction for him."

Banfield's argument seems even more powerful today as the tastes and habits of middle- and working-class Americans have continued to diverge. The admittedly self-defeating present-orientation of lower-income Americans is nonetheless partly explained by the fact that their future prospects are considerably less bright than those of higher-income citizens. In his memoir of his time as a student at Harvard, Ross Douthat noted the remarkable self-restraint of his classmates despite the absence of the old religious and social pressures. Harvard students discipline their appetites for the sake of their fabulous futures. They do not believe in God, but in Douthat's account they do abide by one powerful commandment: "Thou shalt not disrupt thy career" — a law that can feel "as restrictive as a thousand biblical prohibitions." But for lower-class Americans, Douthat observed, "being told to curb your natural appetites for the sake of your future may seem absurd." After all, "it's hard to remember — and hard to see the point — when the world you know, and the future you can expect, lies far beneath the floating cosmopolis of the overclass."

Of course, a pro-marriage campaign that broadcasts the many benefits of marriage and perils of divorce is still a good idea. But like the anti-smoking campaign, such an effort is likely to deepen the class divide rather than shrink it. This is because educated Americans are far more likely to be receptive to the health warnings of a pro-marriage surgeon general. And if a pro-marriage campaign is likely to increase the class divide, then perhaps conservatives should not sell such marriage initiatives by appealing to liberals' concerns about income inequality.

A RELIGIOUS SOLUTION

Given the present-orientation of many poor Americans, any successful effort to strengthen marriage requires more immediate and powerful inducements. Some suggest better access to contraception for poor women, especially "long-acting reversible contraceptives" (LARCs) such as intrauterine devices and implants. LARCs might do some good among the lower classes; contraceptives that require regular use, such as the pill and condoms, are more effective at preventing unwanted pregnancies among the future-oriented middle class. On the other hand, LARCs may simply delay out-of-wedlock births, and they will not do anything to dissuade the many poor women who desire children outside of marriage. In their book Promises I Can Keep, sociologists Kathryn Edin and Maria Kefalas show that many poor women refuse to postpone childbearing, especially given the dearth of marriageable men in their communities. The National Marriage Project and the Institute for American Values, for their part, suggest a variety of reforms, such as ending marriage penalties, tripling the child tax credit, extending the waiting period for divorce, and increasing the number of marriageable men through job-training programs. Some of these reforms in combination with one another might make some difference. If they do, it would be no small achievement.

Nonetheless, Wilson rightly regarded these kinds of proposals as weak substitutes for the powerful social and religious pressures that once stabilized family life. Despite his strong reservations about the old Protestant order, Wilson could not escape the sense that any real remedy to the marriage problem depended on a cultural transformation with substantial help from Christianity. Wilson quietly suggested a need for a religious solution in his conclusion to The Marriage Problem, observing that the cultural restoration of marriage is "not something that can be done by a public policy." Restoring marriage, he wrote, "must be done...by families and churches and neighborhoods," not the state. Reclaiming New York City streets could be accomplished through the application of social science to the problem of crime. But encouraging Americans to stop stepping "on and off the carousel of intimate relationships," as Cherlin put it, seems to require something the Enlightenment cannot provide.

This is the possibility that haunts Wilson's work on marriage, and our democratic experiment. As a nation, we have provided a wider scope for economic and personal freedoms than any other democracy, and we've long depended on Protestant revivals to help order our moral life. Religion, as Wilson correctly emphasized, is not the only way to cultivate self-restraint in a free people. But when he looked for remedies to our marriage problem, Wilson could not see any promising secular alternatives to the old Protestant order.