Re-imagining the Great Emancipator

How shall a generation know its story

If it will know no other?

— Edgar Bowers

The impulse to judge the past in a harsh and unforgiving spirit has probably never been stronger in this country than it is today. This is especially true of those individuals who have been singled out in our national story — individuals whose achievements earlier generations of Americans chose to celebrate. Their names are attached to streets and schools, cities and counties, forests and mountains; their likenesses are rendered in marble and adorn our currency. All these markers of national gratitude and honor draw special ire from contemporary arbiters of rectitude — arbiters who give imperfection no quarter. And let us grant from the outset: All of these individuals from our past, being human, were imperfect.

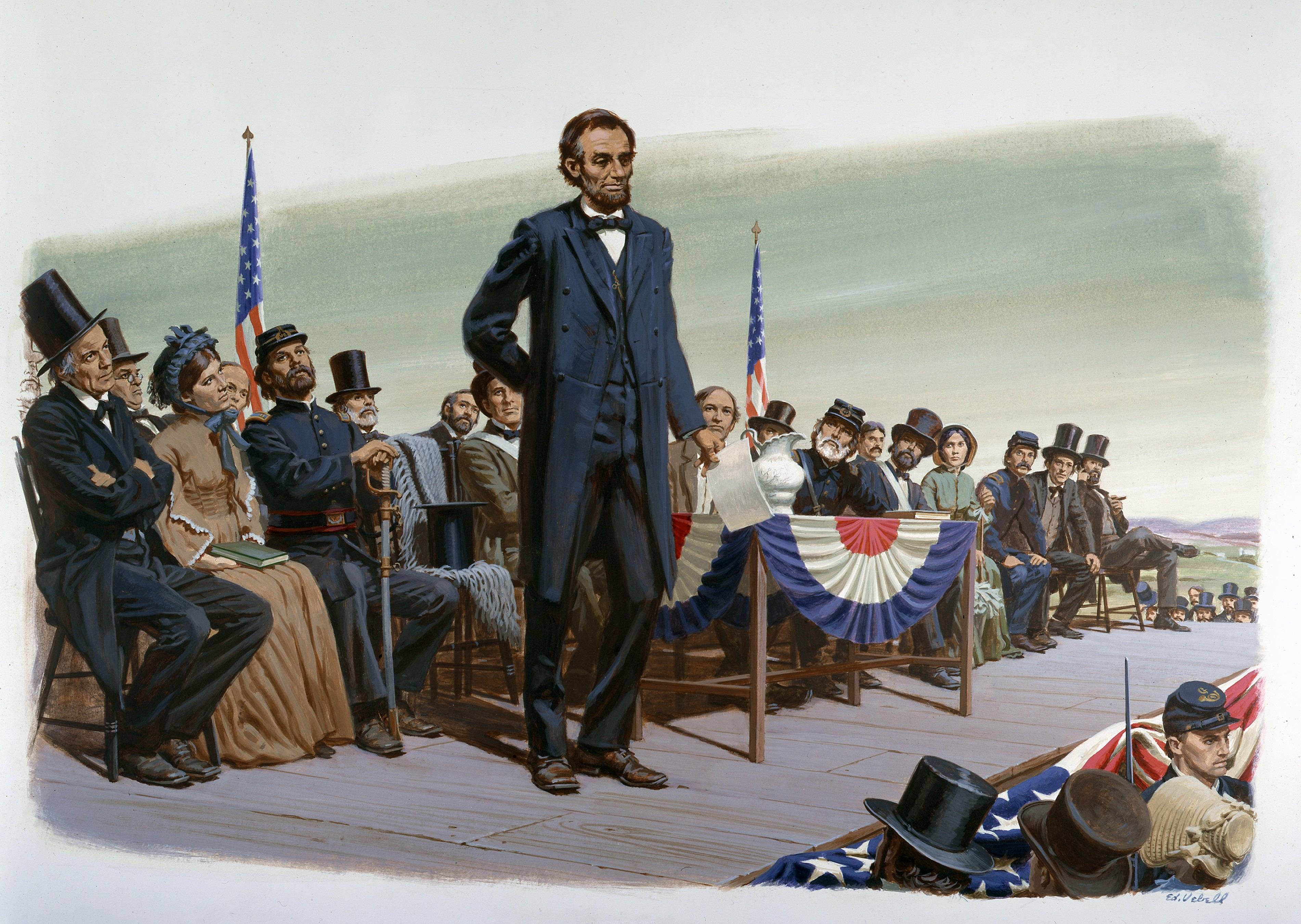

This is the context in which Abraham Lincoln, the Great Emancipator, is being judged in our time and found wanting — grievously wanting. This judgment, almost unimaginable even 50 years ago, invites further inquiry.

My purpose here is not to explain this shift, but to account for Lincoln's continuing grip on our national imagination. Without fail, in every generation since his untimely assassination, we Americans find ourselves compelled to try to make sense of who and what this man was. His background and character, actions and motivations, shallowness and depth — they all pose challenges to our understanding that cannot be ignored. How could such a person emerge out of nowhere, so to speak, to become the towering presence in our national memory that he continues to be?

The astonishment is even greater when one recalls that in his lifetime, this man of sorrows was badgered by allies, despised by rivals, and hated by enemies. Granted, martyrdom does wonders for the reputation of imperfect men — historical examples abound. There may be no reason to doubt that the grief expressed along the railroad tracks of his funeral cortege from Washington to Springfield was genuine, but the fact remains that while he lived, Lincoln never enjoyed broad political support at either the local or the national level. And yet, in retrospect, he soars.

What's more — and here lies the true puzzle — Lincoln still speaks to us. His story of self-discovery amid the most inauspicious circumstances is a story, properly told, that can resonate with young men and women the world over. These individuals yearn for something greater than the offerings of the impoverished political culture they inhabit; they yearn for an avenue of escape, a model with more than a hint of possible grandeur. To such individuals, Lincoln's quandaries, failures, hesitations, and successes continue to speak. He is ever near to all who ponder him.

A REPRESENTATIVE MAN

In the America of the first third of the 19th century — the one out of which the young Lincoln emerged — the conditions of those streaming into its Western edge were overwhelmingly rural, and their prospects were severely limited. Then, and for some time to come, the life of a pioneer was truly solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.

Like so many others who pulled up their stakes and trekked westward, Lincoln's ancestors had tried, failed, and tried once again to secure the prosperity and independence they saw glittering on the horizon. They were not easily dismayed by their disappointments, however. Far from feeling shame over their failures, they transmuted defeat into evidence of personal persistence. What mattered most was not how many times a man might fall, but that he succeed at last in pulling himself up out of the dust.

We can glean a bit more about Lincoln from his admittedly laconic accounts of his past. His namesake grandfather had been overtaken by stealth and murdered by a Native American while trying to clear out a space in Kentucky's wooded wilderness. His father, Thomas Lincoln, was a man who "grew up, literally without education." Thomas had been widowed by the early death of Abraham's birthmother, and he proved a serial failure at farming in Kentucky, Indiana, and Illinois. Lincoln once said that his early life could be summed up in a single line of Thomas Gray's churchyard elegy: "The short and simple annals of the poor." There was not much more to add.

Yet from the little Lincoln does say, and even more by his silences, he invites us to reconstruct the psychic world in which such a youth tried to discover and shape what he might become. Of signal importance was his realization that in the life he was leading, "[t]here was absolutely nothing to excite ambition for education." Thanks to his great size and physical strength, this young man with uncommon yearnings was able to hold his own against the boorishness of his contemporaries. But he had yet to escape from the path of his forebears: a hardscrabble lifetime of backbreaking toil.

As Lincoln was becoming aware of his uncommonness, he had to consider how he was going to present himself to others. This much is clear: His singularity was not a bold claim to be nailed to the prow of his ambition. If anything, Lincoln sought to minimize features of his background, upbringing, and expectations that would set him apart from the ordinary American. He was one of them, and he made sure they saw that. This public persona, at once genuine and assiduously cultivated, expressed itself in a lifelong trait — a singular mixture of relentless ambition and repeated expectation of disappointment.

In the eyes of the regular folk from whom young Lincoln sought first recognition and then the vote, he was truly a representative man. His bearing, manner, and concerns were theirs. And even later on, when his thoughts ran much deeper and his preoccupations veered away from the ordinary, even when he had become a well-remunerated lawyer for the railroads, he took care to maintain and strengthen that bond of familiarity and commonness. The honesty of "Honest Abe" consisted in no small part of his artful recourse to the language, humor, and accents of his youth. His judicious use of pretense — a partial and deliberately edited version of himself — made him a formidable political opponent. Stephen Douglas knew this well enough going into the debates of 1858, having long before taken Lincoln's measure. But for all his uniqueness, there was no pretentiousness in the man. Lincoln's rivals, opponents, enemies, and, most importantly, his public, could not fault him for putting on airs because, in truth, he had none to put on.

His unflinching moral clarity would not have concealed from him the gulf separating his understanding of human affairs from that of his fellow men. But by the same token, that very clarity served as a check on any unjustifiable claims of certainty and moral superiority. In calling from Cincinnati across the Ohio River to the white Kentuckians and Southerners on the other side — a shrewd rhetorical ploy — Lincoln eschewed the abolitionists' righteousness: "We mean to remember that you are as good as we; that there is no difference between us, other than the difference of circumstances." From the prudential beginnings of his political career to the magnanimity of his Second Inaugural Address, he steered clear of presuming to judge the Southern people: "I surely will not blame them for not doing what I should not know how to do myself." He was prepared to "bite [his] lip and keep quiet" for the sake of a larger cause.

LINCOLN'S CLASSICAL MODEL

If we turn to Lincoln's prose before trying to assess his political stance, it is because his writing lies closest at hand — it still speaks directly to us, and requires no intermediary to interpret its plain meaning. But we soon come to realize that the energy and vividness of his language conspire to blur the conventional distinction between speech and action.

Lincoln recognized the coiled power in Biblical cadences and the language of such masters as Shakespeare, Henry Clay, and Daniel Webster. He aspired to do no less, and studied how best to wield words to effect his desired result. Skills honed while trying to persuade juries in county courthouses were ready to be deployed on a greater and far more consequential stage. Lincoln's actions and words illuminate one another; his tactics in speech and action are of a piece.

He also showed an astonishing adeptness in camouflaging his use of the very elements that he was urging his audience to abandon. Three early examples stand out: In 1838, he warned that the unbridled play of passion in American society, evident in the explosive violence of mobs, was jeopardizing the continued existence of our political institutions. His harangue against mindlessness ended with a full-throated appeal for turning to the "solid quarry of sober reason" for recourse. In 1842, addressing a local temperance society, he delivered a scathing critique of the failed methods of that reform movement — their denunciations of drunkards from a position of haughty moral superiority. He presented this critique as bearing on something reformers used to do. Now they know (or is it that now they should know?) better: A "'drop of honey,'" he observed, "'catches more flies than a gallon of gall.' So with men." And in 1852, in his lavish eulogy praising Clay, Lincoln spoke of "the long enduring spell...with which the souls of men were bound to him" as a "miracle." Clay's was a rare kind of eloquence arising from his sincerity and conviction in the justice of his cause. No less important was the great orator's focus: "All his efforts were made for practical effect. He never spoke merely to be heard. He never delivered a Fourth of July Oration, or an eulogy on an occasion like this." Lincoln drew attention to the gulf between what his "beau ideal of a statesman" practiced and what he himself was doing at that very moment. We are entitled to suspect — nay, more than suspect — that Lincoln, too, was not speaking merely to be heard.

One might well wonder what practical effect Lincoln had in mind in delivering that eulogy in 1852. By his own account, he was preoccupied at that time with his activities as a lawyer. "I was losing interest in politics" he wrote; his profession "had almost superseded the thought of politics in his mind." Almost — but not entirely.

Two years later, thoughts and concerns that had lain dormant became all-consuming. When Congress passed Douglas's Kansas-Nebraska Act in 1854, it effectively repealed the restrictions on slavery's expansion that had been embedded in the Missouri Compromise of 1820. That enactment, Lincoln said, "aroused him as he had never been before." And with good cause. For, in Lincoln's understanding of the founders' state of mind, the institution of slavery was regarded by all — Northerners and Southerners alike — as an evil, albeit one that could not be wished away. Cutting off the slave trade and encouraging owners to voluntarily emancipate their slaves would help, but not suffice, to purge the country of this evil; what mattered most was ensuring that slavery not be allowed to expand farther into virgin territories. Only then might the public mind rest once again, secure in the belief that slavery was "in the course of ultimate extinction."

Here lay the great moral challenge of the age. And, contrary to Douglas's professed indifference, this challenge could not be sidestepped by reducing all to a calculation of self-interest: "The plainest print," he maintained, "cannot be read through a gold eagle."

In re-entering the political arena, Lincoln brought not only his steadfast moral compass, but a well-considered mode of combat patterned after that of Roman general and consul Quintus Fabius Maximus Cunctator ("the Delayer"). Like that ancient model, Lincoln rejected launching frontal attacks on fortified positions. He was keenly aware of the continuing struggle between pecuniary interest and moral principle. He bore in mind how hard it is to reverse human behavior and long-held beliefs. And yet, he firmly believed that the times called with the greatest urgency for nothing less.

Nowhere is Lincoln's Fabian mindset better seen than in his lifelong engagement with American chattel slavery. A common abolitionist complaint lodged against Lincoln was his chronic hesitancy. Sometimes, as a would-be suitor, he really didn't know his mind, and was rightly embarrassed by his indecisiveness. Most often, acting as a politician and then as president and commander in chief, his reluctance to act promptly and decisively reflected his acute awareness of how much was still not known regarding unforeseen and possibly unforeseeable consequences. Patience, above all, was needed to persuade the persuadable. These considerations do much to explain his caution, his feints, and his apparent reversals.

THE WORKINGS OF FELLOW FEELING

Lincoln's proceeding by fits and starts did not bespeak any uncertainty or misgivings about fundamental principles. From his first encounters with the realities of slavery, he had a firm understanding that the institution was "founded on both injustice and bad policy" — and he put that judgment into the public record.

To a longtime friend, he could put it more feelingly. Recalling the spectacle (14 years later) of "ten or a dozen slaves, shackled together with irons" on a tedious steamboat voyage, he wrote: "That sight was a continual torment to me." His earlier account of how the slaves were chained was coldly clinical, to be sure: "[T]he negroes," he had observed, "were strung together precisely like so many fish upon a trot-line." At the same time, the account shows his capacity to enter into the concealed feelings of fellow human beings — a point easily missed, or even slighted, today:

In this condition they were being separated forever from the scenes of their childhood, their friends, their fathers and mothers, and brothers and sisters, and many of them, from their wives and children, and going into perpetual slavery where the lash of the master is proverbially more ruthless and unrelenting than any other where; and yet amid all these distressing circumstances, as we would think them, they were the most cheerful and apparantly happy creatures on board.

The rearing of this backwoods rustic had ill-prepared him for the tumultuous spectacle of the city and international entrepôt of New Orleans. There were sights there to astonish — and later, to ponder. Lincoln had much to learn, and being of a meditative and analytic cast of mind even before he had studied Euclid, the wider his horizon spread, the deeper his efforts to make sense of it all became.

Those who try to track Lincoln's changing views of the place of black people in white society are quick to situate his words and beliefs in the context of the fractured public opinion of his time. Lincoln, of all people, need not to have been made aware of the decisive importance of public opinion. And yet, he was not its captive: He was sensitive to its changes and attentive to the task of molding, and even directing it.

From this perspective, what is most revealing about Lincoln's shifting opinions is not the extent to which they track common opinion — what all or most believe at any moment — but where he went his own way. What has been said of a great painter may aptly be said of him: His great gift is revealed not only in what he put into his work, but also in what he left out.

To repeat, Lincoln's mixed record with respect to slavery lies open to judgment. He blew hot and cold over the physical removal of emancipated blacks from the territorial United States — a solution then referred to as "colonization." He initially supported a snail's-paced program of gradual, compensated emancipation: "The change [this measure] contemplates," he insisted, "would come gently as the dews of heaven, not rending or wrecking anything." He begged and beseeched slaveholding states to take up the proposal, and there were many prudential reasons for their doing so. But Lincoln was impelled to offer it by something deeper and rarer: He felt in his heart the humanity of the black slave.

This ability to put himself in another's place manifested itself early on, and never left him. "[T]he most dumb and stupid slave that ever toiled for a master," he observed in 1854, "does constantly know that he is wronged." For Lincoln, slavery was robbery. And he maintained that a native sense of justice and natural sympathy compelled most Northerners — as well as Southerners — to recognize in some fashion the humanity of the slave:

Slavery is founded in the selfishness of man's nature — opposition to it in his love of justice. These principles are an eternal antagonism; and when brought into collision so fiercely, as slavery extension brings them, shocks, and throes, and convulsions must ceaselessly follow. Repeal the Missouri compromise — repeal all compromises — repeal the declaration of independence — repeal all past history, you still cannot repeal human nature. It still will be the abundance of man's heart, that slavery extension is wrong; and out of the abundance of his heart, his mouth will continue to speak.

This unfeigned sense of fellow feeling freed Lincoln to speak his mind without disguising inconvenient facts. In attempting to enlist the efforts of black leaders to promote his plans to settle emancipated slaves in overseas colonies, Lincoln could express himself plainly and forthrightly: "Your race are suffering, in my judgment, the greatest wrong inflicted on any people." "On this broad continent," he continued, "not a single man of your race is made the equal of a single man of ours." He had no illusion that the abolition of slavery might occur during his lifetime; he knew that it certainly did not turn on his electoral success. Yet he took heart from the century-long British campaign to abolish the slave trade. "School-boys," he pointed out, "know that Wilberforce, and Granville Sharpe, helped that cause forward; but who can now name a single man who labored to retard it?"

In the short run, Lincoln knew he might lose to Douglas. But in the long run, right would triumph. And immortal fame might rest on the few, like Lincoln, who labored to end slavery in the republic.

SUCCESSIVE EMANCIPATIONS

In Lincoln's time, as in ours, those who look for and demand a politics of purity have found much to disparage in his Fabianism. Lincoln's constitutional scruples had kept him from dealing the institution of slavery the much-anticipated death blow. His readiness to compromise, and to seek expedient alliances, dismayed the anti-slavery radicals. His explicit distinction between the urgent and the important, as well as his strict adherence to that principle of action, was nothing they could admire. Purists were impatient with his patience.

And indeed, there was no mistaking the president's priorities: first and foremost was saving the union. That urgent task came close to overwhelming all others in what would prove to be the bloodiest post-Napoleonic war of the 19th century. Dealing with the future of the 4 million slaves in the United States would, for the time being, have to take second place.

And yet the two challenges were inseparable in thought and action. The union saved had to be a union in which the Spirit of '76 — a spirit of liberty, not of mastery for some and slavery for others — had been revived and restored. In Lincoln's account, his generation's fathers and grandfathers — men who had asserted a principle and fought for it — were "iron men." Both the slaveholders and non-slaveholders who carried out that revolution viewed slavery as a cancer that could not be excised at once, but that could and should be kept from spreading. After decades of denial and disparagement by apologists for the peculiar institution, the revolutionary fathers' legacy had to be reclaimed. Policies and practices consonant with their moral stance needed to be adopted and followed:

If we do this, we shall not only have saved the Union; but we shall have so saved it, as to make, and to keep it, forever worthy of the saving. We shall have so saved it, that the succeeding millions of free happy people, the world over, shall rise up, and call us blessed, to the latest generations.

Nor could one postpone some hard thinking about the future of the estimated half-million black slaves who were streaming through Northern army lines as those forces moved deeper into the South. Here, too, Lincoln had to think, and to rethink, what policies were desirable and feasible. In words that reveal how little he believed that blacks, already free or lately freed, had a future in the land of their birth, he recommended colonization to a black delegation in terms that confirm he was indeed the white man's president: "[Here were] our white men cutting one another's throats" in a war whose basis was "the institution of slavery and the colored race." "But for your race among us there could not be war," he continued, "although many men engaged on either side do not care for you one way or the other."

This was admittedly a low moment — very likely, as Frederick Douglass thought it, the nadir of Lincoln's temporary stances on the relations between races in America. And it is all the more aberrant when one realizes that Lincoln spoke these words when he had already resolved to issue the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation.

Fortunately, a year later, his aspirations were higher — and perhaps more realistic. The dogmas of the past were proving inadequate to the present; he now wished that the reconstructed government of Louisiana might "adopt some practical system by which the two races could gradually live themselves out of their old relation to each other, and both come out better prepared for the new."

Lincoln's passage from rail-splitter to Great Emancipator was long and hard-earned. It began, as all such individual journeys must, with a process of auto-emancipation: an awareness of what was most lacking in his life, a recognition of the means for supplying that defect, and a steely determination to succeed in liberating himself from illiteracy and ignorance. Such were the indispensable conditions and stages that enabled Lincoln to emerge from the darkness.

Only after this act of self-emancipation was Lincoln positioned to attempt his greatest undertaking: the emancipation of his contemporary white Americans from their corrupt imaginings. Before, during, and after that summer of debates with Stephen Douglas in 1858, Lincoln was relentless in trying to convince his white audience to recognize that we Americans — we, as a people — were not what we once were. Recovering the ancient faith, breathing once again the pure air of the revolutionary era, taking to heart the Declaration's assertion of liberty for all — these had all become matters of urgency. There was no doubt in his mind that an insidious, gradual, but steady campaign had been conducted over the previous three decades to debauch the public mind. The Constitution's "more perfect Union" was being recharacterized as an alliance of convenience from which the states could withdraw on their own; the enslavement of black people was being stripped of its stigma as a barbaric act and coming to be regarded an indifferent matter.

In thus rending those foundational documents of our republicanism to tatters, not only Americans were being robbed of "the principle that is the charter of our liberties." The example of an America continually striving to live up to its loftiest aspirations "gave liberty, not alone to the people of this country, but hope to the world for all future time." However short of that noble goal the country's practices might be, the very assertion of Jefferson's abstract truth served to augment "the happiness and value of life to all people, of all colors, everywhere." Senator Douglas's "don't care" stance toward whether a new territory such as Kansas became a slave state or a free state, in Lincoln's telling, "deprives our republican example of its just influence in the world."

But the emancipation of the blacks held in bondage — a species of property with a value amounting to $2 billion at that time — could also be framed as a bottom-line financial transaction. Of Lincoln's three acts of emancipation — the offer of gradual "compensated" release, the initial proclamation, and the actual abolition of slavery by war — the second was the most visible, as well as the most vulnerable to criticism. In any case, Lincoln himself was under no illusions about the sufficiency of the Emancipation Proclamation of January 1, 1863; it was but a death knell announcing what came later, after his assassination: the 13th Amendment.

Of all the unanticipated results and consequences of that terrible civil war, this abrupt ending to the legal status of slavery could most properly be called "fundamental and astounding." In the eyes of the law, the rights of slave owners to move with their property as they pleased could no longer be equated with the rights of owners of hogs. Henceforward, blacks would be treated as men and women, their humanity no longer willfully ignored. Frederick Douglass, that partisan with the rare gift of thinking above and beyond his partisan zeal, understood how much his people, the newly emancipated blacks, owed to the white man's president. If white Americans were Lincoln's children, black Americans were his stepchildren; they could now rightly claim membership in the same family.

With patience, determination, and good luck, the two races in reconstructed Louisiana might have begun the long process of living themselves out of their old relation. Barely half a year later, however, necessity impelled Lincoln to imagine and ask for more. With the tentativeness of someone tiptoeing through a minefield, he was emboldened to "barely suggest" privately, to the first free-state governor of Louisiana, the possibility of extending the franchise to some black men who had demonstrated their intelligence and gallantry in action. "They would probably help, in some trying time to come, to keep the jewel of liberty within the family of freedom." The stepchild would at long last be seated at the family table.

THE STAYING POWER OF A GREAT VISION

The abiding interest in Abraham Lincoln is unlikely to fade anytime soon. Notwithstanding the criticism from those who admonished him for overreaching as a wartime president, as well as from those who faulted him for failing to pursue the abolitionist agenda with greater vigor, he continues to stand as a central point of reference. He remains singular for displaying, through words and actions, what it means to engage fully and openly with a great moral issue in a complex political setting, one that offers no easy (let alone satisfactory) solutions.

Nor is that all that draws us back to Lincoln again and again as an object worthy of reconsideration. There is also the man himself: His life story presents itself as a model of what was possible under a regime dedicated to the principle of "liberty to all." And Lincoln, in his own time, was not shy of using it for a similar purpose. "I am not ashamed to confess," he once declared, "that twenty five years ago I was a hired laborer, mauling rails, at work on a flat-boat — just what might happen to any poor man's son!" According to Lincoln, the American experiment, as conceived by its founders, was the very antithesis of all previous political orders in which everyone was born and thereby locked into some particular status: once a hired laborer, always a hired laborer; once a slave, always a slave.

The form and substance of the American government, by contrast, had as its leading object "to elevate the condition of men — to lift artificial weights from all shoulders — to clear the paths of laudable pursuit for all — to afford all, an unfettered start, and a fair chance in the race of life." This was Lincoln's world — the world of the self-made man. He could assure members of the 166th Ohio Regiment that he was "a living witness that any one of your children may look to [occupy the White House] as my father's child has." And more generally: "I want every man to have the chance — and I believe a black man is entitled to it — in which he can better his condition — when he may look forward and hope to be a hired laborer this year and the next, work for himself afterward, and finally to hire men to work for him! That is the true system." Lincoln's enduring message is one of possibility and hope. As he came to understand, the audience for that message — America's revolutionary message — would prove to be universal.

Our point of departure has been to try to account for Lincoln's continuing presence in our national consciousness. We are prompted to wonder how such an individual — and an imperfect one at that — shaped himself to the extent that he could, and then went on to shape the sentiments of his countrymen for generations to come. His moral vision was clear; his mode of acting was deliberate and patient. And the example of his own rise from obscurity served to show the truth and relevance of the axioms of a free society as enunciated in the Declaration of Independence. If Jefferson's abstract truth was indeed "applicable to all men and all times," then Lincoln's greatest achievement was to make sure we never forget that.