Marriage, Parenthood, and Public Policy

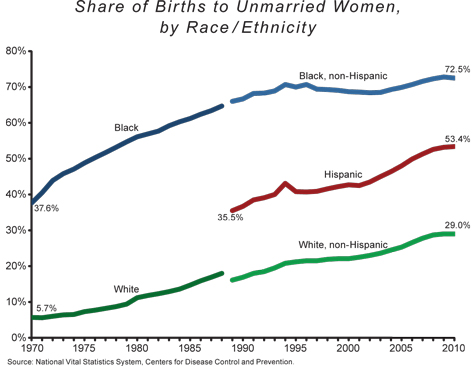

America has been undergoing profound changes in family composition over the last four decades. In 1970, according to that year's decennial census, 83% of women ages 30 to 34 were married. By 2010, that number had fallen to 57%. This drastic decline in marriage rates has coincided with a steep increase in the non-marital birth rate among all demographic groups, from 11% to almost 41% over the same four decades. In 2010, an astounding 72% of births to African-American women were out of wedlock.

These dramatic changes are made all the more significant by the ways in which family composition appears to be related to important social, behavioral, and economic characteristics. Children raised by single parents are more likely to display delinquent and illegal behavior. Daughters raised by single mothers are more likely to engage in early sexual activity and become pregnant; their brothers are twice as likely to spend time in jail as their peers raised by married parents. They are less likely to finish high school or get a college degree. And they are four to five times as likely to live in poverty as are children raised by married parents. These intergenerational trends are prominent among both the causes and effects of America's limited social mobility.

Thus, as the nation confronts the stubborn problems of economic inequality and immobility, the rise in the number of single-parent families matters a great deal. The sexual revolution of the 1960s and '70s paved the way for these massive shifts in family life, and these shifts are now making it more difficult for a huge portion of the current generation to get its fair shot in the land of opportunity.

So what is to be done? Answers are difficult to find, but it's not for lack of trying. Both public and private institutions have attempted over the past four decades to decrease the rate of births to unmarried women, either by providing birth control or abstinence education or by encouraging marriage. The federal government has spent billions of dollars trying to counteract the poverty and other social consequences that follow in the wake of the breakdown of the family.

The results so far have been mixed at best, but they do suggest some patterns. Some kinds of interventions appear to make a modest difference on the margins, while others appear to be almost entirely ineffectual. But analyses of these patterns are too often distorted by ideological commitments on all sides. Given the magnitude of the problem, it is essential that analysts and policymakers come to terms with what our experience can teach us so they can seek to build on what works. It is easy to stand back and say that government can't make families, and it is also surely true. But it is nonetheless apparent that there are some ways that public policy, working together with the institutions of American civil society, can help create the circumstances to better enable families to form.

THE RISE OF SINGLE PARENTING

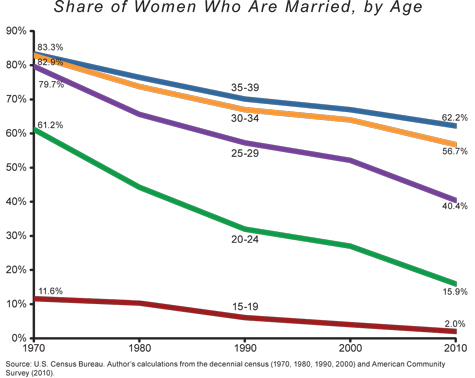

The shape of the typical American family has changed dramatically over the past four decades, in large part due to a precipitous drop in marriage rates. For almost every demographic group, whether broken down by age, education, or race and ethnicity, marriage rates have declined nearly continuously since 1970. The chart below shows the decline in marriage rates for five age groups from 1970 to 2010.

The decline has been dramatic. Marriage rates for 20- to 24-year-olds, for instance, fell from 61% to 16%, a decline of almost 75% in four decades. This drop in young marriages is not so surprising: The couples who do get married now tend to wait longer to do so than they would have a generation ago. What is more surprising is that the marriage rate for older cohorts has fallen as well. The rate for 35- to 39-year-olds, for instance, declined by 25%, from 83% to 62%. The only exception to the pattern of decline was for women with a college degree or more (not shown in the prior chart). After a modest decline of about 11% between 1970 and 1990, the marriage rate for college-educated women stopped declining and even increased by about 1% between 1990 and 2010.

This decline in marriage rates has coincided with steep increases in non-marital birth rates. As the chart below shows, in the same four decades, the non-marital birth rate for African-Americans increased by more than 90%, from 38% to 72%. In 2010, the Hispanic rate was 53%, a 50% increase over 1989 (when data on Hispanic birth rates first began to be collected separately from non-Hispanic whites). The rate for non-Hispanic whites, which stood at 16% in 1989, had increased to 29% by 2010, a larger increase in percentage terms than for any other group over that period.

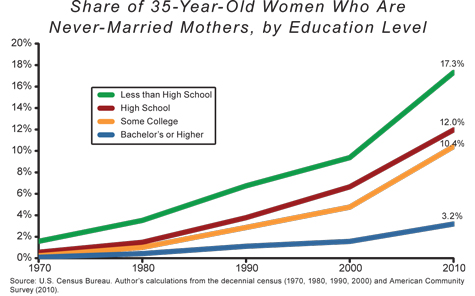

Throughout the 40-year period from 1970 to 2010, women with less education were always more likely to give birth outside marriage, but by 2010 the differences among educational groups had become enormous. As the chart below shows, a 35-year-old woman with less than a high-school degree, for instance, was more than five times as likely to be both never married and a mother than a woman with a bachelor's degree or more.

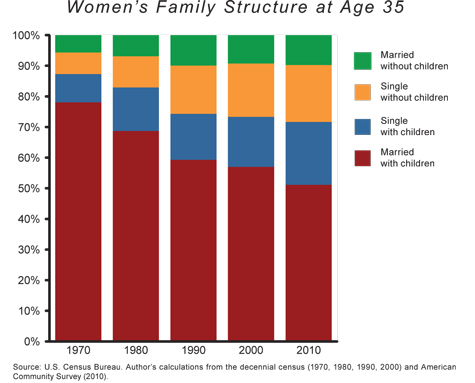

Taken together, the drop in marriage rates and the increase in non-marital birth rates, combined with the substantial increase in the number of married couples who remain childless, have resulted in a dramatic shift in the composition of the American family.

In the chart that follows, data from the five decennial censuses from 1970 to 2010 are used to divide 35-year-old women living in households into four mutually exclusive groups: married with children, married without children, single with children, and single without children. Over the four-decade period, the percentage of married-with-children households declined by well over a third to just 51%. By contrast, the percentages of all three other types of households increased: married without children by 72%, single with children by 122%, and single without children by 165%.

The consequences of these changes in family composition are shouldered in large part by the children of single-parent households. These young people make up a fast-growing share of American children. In 1970, 12% of children lived with a single parent at any given time; over the next 40 years, that number increased by 124%, rising to 27% of children in 2010. Over the course of their childhoods, as many as half of all American children will spend some time in a single-parent household.

The available evidence on what growing up in single-parent households means for children suggests this enormous increase in the number of such households is yielding very troubling consequences. Poverty is perhaps the most harmful of these consequences. According to the Census Bureau, in 2012 the poverty rate among children living with only their mother was 47.2%; by contrast, the poverty rate among children living with their married parents was 11.1%, meaning that a child living with a single mother was almost five times as likely to be poor as a child living with married parents.

One of the most troubling aspects of this trend is the negative effect that poverty has on childhood development, especially among children who are poor in their early years. Given that the major cause of the rise of single parenting is the increase in non-marital births, it follows that many children in single-parent families experience poverty from the moment of their conception. Research shows that mothers giving birth outside of marriage are less likely to have complete prenatal care and are more likely to have babies with low birth weights and other health problems, all of which disrupt child development.

And a higher likelihood of living in poverty is far from the only challenge faced by children who grow up in single-parent families. Until the 1990s, the scholarly world mostly followed the lead of influential developmental psychologist Mavis Hetherington, who concluded that most of the children of divorce soon recovered from the changes in their households and showed modest if any long-term consequences. But a review of 92 empirical studies by Paul Amato, published in 1991, showed abundant evidence that children from divorced families scored lower on several measures of development than did children living in continuously intact families. Then, in 1994, sociologists Sara McLanahan and Gary Sandefur published Growing Up with a Single Parent, after which it was nearly impossible to deny that there were serious costs to single parenting. Based on sophisticated analyses of four nationally representative data sets, McLanahan and Sandefur concluded that "children raised apart from one of their parents are less successful in adulthood than children raised by both parents, and...many of their problems result from a loss of income, parental involvement and supervision, and ties to the community."

Since 1994, the literature on the effects of single parenting on children has continued to grow. A partial list of these effects includes an increased likelihood of delinquency; acting out in school or dropping out entirely; teen pregnancy; mental-health problems, including suicide; and idleness (no work and no school) as a young adult. Married parents — in part simply because there are two of them — have an easier time being better parents. They spend more time with their children, set clear rules and consequences, talk with their children more often and engage them in back-and-forth dialogue, and provide experiences for them (such as high-quality child care) that are likely to boost their development. All these aspects of parenting minimize the kinds of behavioral issues that are more commonly seen among the children of single parents.

Many of these problems have consequences for future generations. One of the reasons it is so difficult for people born into poor families to lift themselves into the middle class is that the good jobs that pay well are often out of reach for those who grew up in poor neighborhoods. This should not be surprising in an economy dominated by high-tech industries and global business: An increasing share of jobs that pay well require a good education, which is much harder to obtain in failing schools in impoverished neighborhoods. And, regardless of the quality of their schools, children from single-parent families on average complete fewer years of schooling, which is correlated with lower adult earnings. This correlation makes it more likely that the cycle of poverty continues into the next generation.

The negative consequences of the rise in single parenting are not limited to those in single-parent families. The trend affects everyone. There are, of course, the immediate costs imposed on taxpayers to pay for government benefits for impoverished single mothers and their children. Single mothers often receive the Earned Income Tax Credit, which can be worth over $6,000 per year for a mother with three or more children, as well as the Additional Child Tax Credit, which can be worth up to $1,000 per year for each child. Female-headed families are also more likely than married-couple families to receive other welfare benefits such as housing, food stamps, medical care, and other benefits which can be worth several thousand dollars a year.

More important, however, is the human capital lost. Children raised by single parents tend to perform more poorly in school, and this fact appears to be one reason why America's children are falling seriously behind students from other countries in educational achievement. The most recent data from the Programme for International Student Assessment show that American children rank 21st in reading and 31st in math. Equally disturbing, the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development has recently published a comprehensive assessment of proficiency in adult literacy, numeracy, and problem-solving across 24 nations. The U.S. was near the bottom in almost every category. For example, 9.1% of American adults scored below the most basic level of numeracy compared to 3.1% of Finnish, 1.7% of Czech, and 1.2% of Japanese adults. The skills assessed by the survey are closely related to adult earnings. Of course, single parenting is not the sole reason American children and adults fare so poorly on international comparisons. But the evidence points unambiguously to the conclusion that single parenting is one factor that accounts for the poor performance of the nation's children.

Many of the problems we associate with failures of American economic policy — especially the persistence of a high poverty rate despite the billions of dollars a year we spend on relief efforts — can also be attributed to family breakdown. Indeed, it is not an exaggeration to say that America's social problems and its economic problems are thoroughly intertwined with the decline of marriage and the rise of single parenting.

CAN ANYTHING BE DONE?

As the rates of single parenthood have risen and the consequences have become clear, all levels of government from local to federal have attempted to implement policies to address the problem but with limited success. These attempts generally fall into four categories: reducing non-marital births, boosting marriage, helping young men become more marriageable, and helping single mothers improve their and their children's lives.

The first class of policies, those aimed at reducing non-marital births, have met with some success, especially among teens. Teen pregnancy rates have declined almost every year since 1991, and the number of teen births has declined by more than 50% since that time.

It is difficult to identify which specific factors have contributed the most to this success, but several conditions conducive to attacking a national social problem are present in the case of teen pregnancy. There is nearly universal agreement among parents, religious leaders, teachers, and elected officials that teens should not get pregnant. This harmony sends an unambiguous message to teens. Although Republicans and Democrats fight over whether programs should focus on promoting abstinence or birth control, most programs at the local level seem to include both approaches. Teens get a host of messages from their school courses, from community-based organizations, from their parents, and from community leaders that sex can wait and that pregnancy is an especially bad idea.

Surveys show that teens agree with both messages but most of them try to implement only the second — and then indifferently, despite the widespread availability of birth control. As the pregnancy and birth rates show, the situation is improving, but the U.S. still has the highest teen-pregnancy rates of any nation with an advanced economy, and more must be done to address the problem.

The Obama administration has implemented two prevention initiatives that support model programs that have shown strong evidence of success in reducing sexual activity or pregnancy rates among teens. About 200 local programs are now operating under these new funding sources, and the administration has created an elaborate plan for evaluating the local programs. There are also a handful of national organizations, such as the National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy, which are trying to keep the nation's attention focused on prevention programs and are using social media to reach teens directly.

Though public policies have been successful in reducing teen-pregnancy rates, the problem of non-marital pregnancy is now greatest among adults in their 20s and 30s. Non-marital birth rates among young adults had been increasing steadily until recently, and though the rate is now declining for most age groups, there are still far too many non-marital births.

Fortunately, this is one important social problem against which we have the knowledge and experience to make progress. High-quality modeling research by Georgetown University's Adam Thomas and others shows that additional spending on media campaigns and free coverage of birth control, especially long-acting methods, for low- and moderate-income women would further reduce pregnancy and birth rates and even save money. In addition to this modeling, there is an emerging body of empirical research on the impact of making effective birth control available to young adults.

For example, one recent study of free coverage for long-acting reversible contraceptives (such as implants and intrauterine devices) found that not only did they reduce unintended births but they also reduced abortion rates. Similarly, a recent study from the National Bureau of Economic Research found evidence that "individuals' access to contraceptives increased their children's college completion, labor force participation, wages, and family incomes decades later."

Some Americans of course object to contraception for moral or religious reasons and will therefore object to these programs as well. But for those whose objections have been rooted instead in skepticism about the utility of these approaches or their cost-effectiveness, the evidence of their success is increasingly beyond question. They are not sufficient to stem or reverse the trends of declining family formation, but they can help and should be further implemented.

PROMOTING MARRIAGE

The second, and perhaps most straightforward, solution to the problem of rising non-marital birth rates is to increase marriage rates. But reversing decades of declining marriage rates is turning out to be exceptionally difficult. Many civic organizations, especially churches, view encouraging marriage as part of their overall mission. Some churches have organized activities to strengthen marriages or help couples survive crises in their relationships. The Catholic Church, in particular, has long insisted on premarital counseling. We have very little reliable data on precisely how many such programs there are and very little evidence regarding their effects on marriage rates or marital satisfaction. We cannot know whether the marriage rate would have been even lower if these civic organizations had not been actively supporting marriage, but it is self-evident that they have not been able to stem the institution's remarkable decline.

Clearly, more evidence and data analysis are called for on this front. But it is also clear that a problem of this scale calls for serious public as well as private action. Apart from providing funds (including tax breaks) for organizations that provide marital counseling and paying for or creating public advertising campaigns about the value of marriage to children and society, however, the federal government has generally not done much to help find a solution to the problem.

The presidency of George W. Bush provided an exception to this rule, as the federal government implemented several marriage-strengthening programs that were executed by state and local organizations, most of them private. These programs provide an initial body of evidence about the possibility of a larger role for public policy in strengthening marriage, and the evidence they provide is decidedly mixed.

The Bush marriage initiative involved several separate strands, including three large intervention studies. One of these studies tested whether marriage education and services would help young, unmarried couples who have babies together improve their relationships and perhaps increase the likelihood that they would marry. Another tried the same approach with married couples, aiming to improve and sustain their marriages. The third studied community-wide programs that adopted a number of strategies simultaneously to bring attention to the advantages of marriage and to strengthen existing marriages at the local level.

The first two initiatives were tested by gold-standard studies; the third was tested by a cleverly designed study that nonetheless involved a less reliable research strategy. In addition to these three initiatives, the Bush administration enacted a grant program that funded 61 healthy-marriage projects at the local level with a total of $75 million per year. Taken together, these four major activities, and others funded through the Department of Health and Human Services, stand as the most thoroughgoing attempt ever by the federal government to have an effect on marital satisfaction and marriage rates.

The results have been disappointing. The community-wide initiative, carried out in three cities, produced virtually no effects in the test cities as compared with three control cities. There have been few high-quality evaluations of the $75 million grant program, so no claims can be made about its effectiveness. (There are now a few ongoing studies of these programs, but none has published results based on rigorous analysis.)

The program for married couples has reported results after 12 months. The effects of the program were small but statistically significant. Couples participating in the program reported modestly higher levels of marital happiness, lower levels of marital distress, slightly more warmth and support for each other, and more positive communication skills. Spouses in the program group also reported slightly less psychological and physical abuse than control-group couples. The evaluators concluded that the program's positive "short-term effects are small, but they are consistent across a range of outcomes." A follow-up report of the results at 30 months after the program began is due out soon. If the same kinds of effects are still present or are even stronger at 30 months, there may be room for some optimism that married low-income couples can profit from marriage education and support services of the type offered by the Bush program.

The program aimed at helping young couples with an out-of-wedlock baby had some limited success. The test was set up in eight cities, with randomly-assigned controls in each site. Six of the sites produced no important effects on the couples, and the Baltimore program showed a few negative ones. But the Oklahoma City test showed a host of positive effects. The Mathematica Policy Research firm conducted studies of the Oklahoma City site and reported that, 15 months after the program began, participating couples were superior to control couples in skills such as resolving disputes, planning finances, expressing positive feelings for their partners, and using good child-rearing techniques.

The effects of the programs for these unmarried couples, however, appear to have been only temporary. When researchers checked again 36 months after the program started, the positive results seen in Oklahoma had dissipated, as had the negative results of the Baltimore test. A program in Florida began to show negative results after three years, but the other test programs showed hardly any effects at any point. Thus, of eight sites, the only good news was from Oklahoma, and most of the encouraging results seen after 15 months had disappeared less than two years later. The couples in the Oklahoma program, however, were 20% more likely to still be together at 36 months than were the control couples in the same study.

The modest success of the Oklahoma City experiment may suggest that something about the program worked. Given the resources invested in the Bush marriage initiative and the programs' quite limited success, however, there is little reason to be optimistic that programs providing marriage education and social services on a large scale will significantly affect marriage rates.

HELPING YOUNG MEN

The young fathers of the children born out of wedlock present one of the main barriers to more successful marriages and fewer non-marital births. There are currently almost 5.5 million men between the ages of 18 and 34 who have less than a high-school degree. Large portions of them grew up in single-parent homes themselves, lived in poverty, and attended failing schools as children. A large percentage of them have prison records. Not surprisingly, poor young women are reluctant to marry them.

These women are, however, willing to have babies with them. After many years of interviews and living in poor neighborhoods, sociologist Kathryn Edin and several research partners have assembled an extensive picture of how these young men are viewed by the young women in their neighborhoods. When asked why they don't want to marry the fathers of their children, the mothers indicated that they didn't trust the young men, that the men didn't work steadily or earn enough money, and that they were too often violent. This description mirrors that of the "cool-pose culture" that Orlando Patterson and other anthropologists apply to men who willingly embrace a lifestyle of hanging out on the streets, working as little as possible, and avoiding binding commitments to family, community, or the mothers of their children. Patterson concludes that the cool-pose culture has evolved to meet current circumstances — especially the difficulty of landing a good job with decent wages — and that no one has figured out a way to break through this culture.

The situation these men face is not fundamentally a result of failed public policies; it is a result of a whole culture of non-marriage, non-work, and serial relationships. It is therefore unlikely that adopting new government policies is going to transform these men into successful husbands and fathers. There are, however, four policy approaches that may help make a difference at the margin.

The first is to address the problem of incarceration. We should start by figuring out ways to avoid putting young men in jail unless they have committed violent offenses. A large number of these young men are incarcerated under mandatory-sentencing laws even for non-violent crimes, and especially for drug-related crimes. Sentencing laws enacted in response to high crime rates in decades past were not irrational or pointless, but it is time for our society to confront their negative consequences and to seek sensible reforms, at both the federal and state levels.

Given the huge proportion of poor young men with prison records, we also need to help these men become productive members of their communities when they get out. There are many programs already in place that attempt to help men who have spent time in prison get jobs and re-integrate into society. One important experimental program in New York City and other locations aims to figure out ways to help young men in juvenile-detention facilities acquire the education, training, counseling, and commitment to personal responsibility they need to avoid subsequent arrests. So far, the research on these programs has been only moderately encouraging. Many of the programs are still in progress, but perhaps the most widely accepted finding is that services, including employment services, for men coming out of prison do not raise employment rates but do reduce recidivism rates. Given this limited but meaningful success with those who have prison records, it seems reasonable to conclude that we should continue and expand research and programs to help young high-school dropouts — whether or not they have spent time in jail — stay out of jail and find jobs.

A second, related set of ideas is aimed at finding ways to get these young men better qualified for and committed to employment. The program of this type that has had the most success so far is called career academies, in which students organize into small learning communities to participate in academic and technical education for three or four years during high school. Perhaps the most important aspect of the program is the opportunity students have to gain several years of experience with local employers who provide career-specific learning experiences. An eight-year follow-up of young adults who had participated in career academies showed limited effects on young women but major effects on young men. Young men who had been in the program were about 33% more likely to be married, were about 30% more likely to live with their partners and their children, and earned about $30,000 more over the eight years than the men in the randomized control groups. Expanding the reach of career academies, especially in high-poverty areas, would be a wise investment.

A third policy approach would be to provide young single workers without custody of children with an earnings supplement similar to the Earned Income Tax Credit. The goals of the program would be to provide an incentive for young men to seek and accept low-wage jobs and to increase their income so they would be more likely to continue working. An experiment testing the effects of this policy is now being implemented in New York City by the research firm MDRC. Young single workers will be eligible for wage supplements of up to $2,000 per year. Their response in terms of employment, earnings, and social relationships will be carefully tracked and compared to randomly assigned controls. If research on the EITC is any indication, this program should increase work rates and earnings and may have additional positive effects on the participants' social lives.

A fourth intriguing policy, again with some evidence of success, would provide job services to fathers who owe child support to help them find steady employment and increase their child-support payments. A program of this type initiated in Texas found that men who had little money to pay child support would, with the help of the program, search for and accept jobs. The study also found that the work rates and child-support payments of these men increased. The federal Department of Health and Human Services has provided funds to a total of seven states (not including Texas) to implement and evaluate similar programs. If the Texas results are replicated, other states should launch employment programs for poor fathers who have difficulty paying child support.

By implementing policies to help poor young men develop the skills they need to break out of a destructive cultural cycle, we can help them become more responsible workers and better fathers. And helping young fathers could help young mothers by giving the men in their lives the tools they need to become responsible husbands and fathers.

HELPING SINGLE MOTHERS

As long as the deep social maladies underlying non-marital childbirth go unaddressed, young single mothers and their children will continue to need help. Today, there are millions of single mothers who do not have the education, skills, or experience necessary to earn enough to escape poverty. So in order to help them provide for their families, the federal and state governments work together to provide cash payments, work subsidies, and a host of work-support benefits.

Since the Great Depression, an evolving set of government welfare programs has helped to meet the basic needs of poor mothers and their children. The most recent manifestation of these programs is a product of the successful 1996 welfare-reform legislation. Instead of a simple cash transfer (as is done with Social Security), the government's major cash-welfare program, Temporary Assistance for Needy Families, is contingent upon work for those who are capable of working. Recipients' wages are then subsidized with an assortment of work-support benefits: cash through the EITC and the Additional Child Tax Credit, medical care, food benefits through the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (formerly known as food stamps), and child-care services.

A typical single mother earning, say, $10,000 might receive cash from the EITC and the Child Tax Credit, SNAP benefits, and Medicaid coverage for her children. The children also receive school-lunch and possibly other nutrition benefits. The family might also receive help with child care, although there is not enough money appropriated for all eligible mothers to receive such a subsidy.

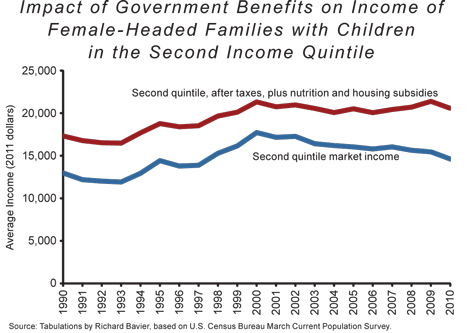

The chart below shows the financial impact of these benefits for single mothers in the second income quintile (incomes between about $11,700 and $24,200 in 2010). The market income of these women (mostly earnings, shown in the bottom line) is increased substantially by the work-support benefits provided by government (as shown in the top line). The chart also shows that both measures of income increased beginning in the mid-1990s when mothers' work rates increased dramatically, primarily due to the work requirements in welfare reform along with a strong economy.

Perhaps the most important feature of this system is that it provides motivation for poor mothers to work because by doing so, even at the low-wage jobs for which most are qualified, they can bring themselves and their children out of poverty. An additional benefit of this system is that a modest number of these mothers prove to have the doggedness and talent to move up the job ladder and increase their earnings over a period of years.

The argument is sometimes made that single mothers are becoming too dependent on government benefits and that only the truly destitute should receive means-tested benefits such as food stamps. But the work-support system has enabled millions of mothers and children to live securely despite limited earnings. Further, many of the mothers who would in the past have been completely dependent upon welfare have now joined the workforce, in large part because of the strict work requirements attached to these benefits.

Politicians should draw a clear distinction between means-tested benefits that go to able-bodied people who do not work and those that go to working people. It is especially important to maintain the benefits for low-income parents living with or supporting children.

Given the current non-marital birth rates and trends, millions of American children over the next several decades will live in families headed by single mothers. Since it is clear that we cannot produce public policies that will give them two married parents, we should do what we can to protect many of these children from the vicissitudes of poverty by continuing and even expanding the nation's system of strong work requirements backed by work-support benefits.

THE LIMITS OF POLICY

The United States has long been considered the land of opportunity. Americans take particular pride in Horatio Alger stories that seem to prove that anyone willing to work hard enough can make it in our country. That is why reports of rising income inequality and low levels of income mobility have received so much attention; they undermine the ideal of the poor young American able to pull himself up by his bootstraps.

As we have seen, children born out of wedlock are far more likely to live in poverty, and they are far more likely to remain poor as adults. Children raised by two married parents, on the other hand, are not only more likely to have a stable financial situation at home, they also reap the benefits of having more parental investment in their development, better schools, and better neighborhoods. As these patterns reproduce themselves over generations, non-marital childbearing and the poverty that so often accompanies it help to create and sustain two societies within the same nation. Our changing, knowledge-based economy is growing less forgiving of a lack of education, making it hard for young people without college degrees or specialized skills to earn a decent living. And now the last and perhaps most important piece of the traditional American system for building equal opportunity — the married-couple family — is coming apart.

If we want to address the challenges of income inequality and immobility, we must address one of their main causes — non-marital births and single parenting. Maybe stable, married-couple families will never again be the dominant norm, but if so the children who are raised by such traditional families will continue to have yet another advantage over their peers who have minimal contact with their fathers, live in chaotic households, and are exposed to instability at home as their mothers change partners.

Our society and culture will no doubt continue to change, but our children will continue to pay the price for adult decisions about family composition. Public policies cannot ultimately solve this problem, but those that prove themselves capable of ameliorating some of the damage are surely worth pursuing.