Liberalism, Properly Understood

In the past few years, liberalism, broadly understood, has found itself under attack by some smart and thoughtful traditionalists. Their charges are serious, and deserve to be carefully considered. But ultimately, they suffer from too thin a conception of just what liberalism is, and what the tradition that has grown up around it has offered us.

Patrick Deneen's 2018 book Why Liberalism Failed has served as a major focal point for this criticism. Deneen is a political theorist at the University of Notre Dame, and his book is a work of political theory, cultural criticism, and at times tough-minded polemic. It attempts to demonstrate why the early modern liberalism of Thomas Hobbes, Francis Bacon, and John Locke, among others, resulted in our deracinated culture, atomistic families, titanic inequality, and dysfunctional politics. Liberalism is failing not because it has been tried and found wanting, Deneen argues. Rather, liberalism's success is its undoing: "As liberalism has 'become more fully itself,' as its inner logic has become more evident and its self-contradictions manifest, it has generated pathologies that are at once deformations of its claims yet realizations of liberal ideology."

Deneen combines classical and modern liberalism in his critique: Both consume social, moral, and religious capital and replenish nothing. There are no exceptions made for a James Madison, Alexis de Tocqueville, Lord Acton, or Adam Smith, or any of the other classical liberal thinkers one might list as guardians of a liberty-minded constitutionalism.

Many of Deneen's criticisms of our society are hard for American conservatives to dismiss. On culture, family, religion, politics, and education, his observations ring true and his diagnoses are persuasive. Contemporary liberalism holds itself aloof from deeper pre-liberal sources of human flourishing and has become a fideistic dogma of choice and autonomy for their own sakes. Such liberalism involves free individuals creating values through the choices that they make without rational discrimination as to the objective merit of those choices and whether they contribute to human flourishing.

For these transgressions, Why Liberalism Failed indicts liberal political theory, which Deneen argues informs our constitutionalism, ultimately warping us into apolitical and dislocated individuals who abide and welcome any number of self-destructive social experiments. This is the inevitable outcome of Lockean liberalism, by which (as Deneen describes it) individuals create a political society for the largely private purposes of protecting their security and property. Not only does the American constitutional order lead us away from strong forms of citizenship, but it trains our focus on ourselves and what will lead to our individual satisfaction. Our constitutional order never leads us to support the common good and contend for justice. As a result, we gradually reduce ourselves to liberal individualists endlessly gnawing on our preferred bone. We are unwilling to act with public regard because we cannot see the point of such striving. It is a regime flaw.

In this respect, Deneen must accord near-creedal status to Justice Anthony Kennedy's opening sentence in the majority opinion in Obergefell v. Hodges: "The Constitution promises liberty to all within its reach, a liberty that includes certain specific rights that allow persons, within a lawful realm, to define and express their identity." Justice Antonin Scalia's lament that "[t]he Supreme Court of the United States has descended from the disciplined legal reasoning of John Marshall and Joseph Story to the mystical aphorisms of the fortune cookie," must be canonically wrong, according to Deneen. Kennedy was our great constitutional sage, and Scalia was a confused, if well-meaning, heretic.

Perhaps the ultimate reason, however, for the abiding appeal of Deneen's book is that he raises without flinching a stark question: Should the American constitutional regime continue to exist? Like many progressives of the late-19th and early-20th centuries, he is doubtful that it should. But where those early progressives were giddy over this prospect, Deneen seems largely resigned to the inevitable fate of our liberalism. Many conservatives feel the same in the wake of foundational challenges to marriage and religion, and in the face of what seems to be a desire to drown out their public voices with the megaphone of identity politics. When Deneen states that "[t]he fabric of beliefs that gave rise to the nearly 250-year old American constitutional experience may be nearing an end," he increasingly carries thoughtful religious conservatives, especially some of the younger voices, with him.

THE SILENT ARTILLERY OF LIBERALISM

It is here, though, that we can really begin to turn a critical eye on Deneen's post-liberal potpourri. Several scholars have sharply critiqued Deneen's insistence that America is ill-founded because its foundational liberalism shaped the Constitution. These same scholars note that the stance of our natural-rights tradition is a sober realism about the contents of human freedom and one that has gone hand in hand with laws that have supported family, religion, public morality, and the inculcation of virtue.

Deneen does not so much dispute this as suggest it was always bound to fall apart. America is built on liberalism, which he sees as a deeply flawed philosophy. We are destined for a sorry end because of our beginning in the currents of liberal dissolution, which eventually broke up the solid mass of the pre-liberal classical and Christian inheritances that were present at the American founding. We had strong religion, community, mores, and virtue once, but liberalism slowly washed these pillars away. Such a liberalism does not appear to lead to human flourishing, or to satisfy the yearnings and the questioning of human souls.

But is ours in fact such a liberalism? Deneen insists it is, and that the problem is fundamentally rooted in the strict limitation that liberalism imposes on the scope of human reason — reducing reason to what it can prove empirically, or insisting that reason can show us only historically verifiable truths. From this follow two apparently contradictory results: the god-like powers attributed to science and experts, and the devaluation of human longing and curiosity to merely subjective phenomena. This modern deformation of reason robs us of the capacity to understand the contents of freedom and denies that our wondering and wandering nature can find answers to life's questions.

Moreover, once this debased conception of reason becomes the norm, it cannot help but deform our politics. If human reason's capacity to understand the good is eviscerated, then the deliberative aspect of a liberal constitutional order becomes ridiculous, and a rapid descent into the froth and frenzy of power and will is inevitable. The means of government are then employed without understanding and without wisdom, as citizens clamor for their desires to be sated and fight one another in tribal fashion.

A thinker crucial to Deneen's understanding of the inescapable downward cycle of this sort of liberalism is Thomas Hobbes. His legendary observation in Leviathan (published in 1651) is that man is just a collection of sensible appetites and that human will is just what comes uppermost in these desires. If man is merely appetite and desire, then what is reason and what role does it play in human action? For Hobbes, desire spurs ratiocination. We need desires, Hobbes says, because they develop our wit. In particular, we need a desire for power if we are to be rational. The good is merely the thing desired by each particular person. But with the pursuit of desire comes conflict, as we beasts brush against one another in competition for the things desired which of necessity cannot be shared. Hence the need for the state.

Hobbes's kind of social-contract theory asserts that, in establishing and sanctioning law, states provide the means for man to improve his lot by being able to rely on a predictable state and its progeny or protectorate, civil society. With no intrinsic way to order our wills and their desires, we need an incredibly powerful state to compel the observance of rules.

But this story of the state civilizing recalcitrant man told in different ways by Enlightenment political theorists has lost its appeal to late-modern liberals. The very idea that we require a civilizing influence at all has gone out of fashion. The sovereignty of the state is no longer the focus, and the sovereignty of the will has gradually taken its place. The late-modern mind affirms autonomous liberty or the affirmation of the self without really knowing oneself.

This rightly brings us to the dogma of our times — the supremacy of choice and equality, for their own sakes. The liberalism that overarches this negative anthropology must be strongly opposed to any conception of man's freedom premised on a normative human nature, that is, a freedom that more fully becomes itself and achieves human excellence when its choices realize and develop the goods of human nature. It's the very fact of human nature that is dismissed by such liberalism; there is, ultimately, no reason why the being entrusted with language and the giving of reasons for his actions applauds things like courage, wisdom, temperance, or prudence, as opposed to cowardice, foolishness, indulgence, or folly. Moreover, our status as embodied finite beings who love others because of our mutual dependency signals no clear or transparent meaning about our relational human nature to illiberal liberals.

To the question "who is man?" such a liberalism can only respond that man is pure potential, pure freedom. Freedom is not responsibility to truth; it is merely freedom from. This means that the deepest callings of our freedom — urgings that cannot be vanquished, namely a freedom with and for others, and a freedom under law — are really sources of authoritarianism and must be suppressed. Thus we understand the wrath of contemporary liberalism against the unchosen obligations of religion and family. But this contemporary liberal animus directed at sturdy, relational obligations is an attack on the spirit of liberty within liberal democracy. It is as much an assault on liberalism as a working out of liberalism. Deneen and other post-liberal critics take this to mean that liberalism was always self-destructive. But this is by no means the only way to read the evidence.

A SENSE OF THE SACRED

One of the fears Alexis de Tocqueville expresses in Democracy in America is that Americans would no longer understand their restlessness for the worthy sign that it is, illuminating our souls and their eternal worth. As Tocqueville memorably notes, our unease in the midst of abundance indicates that we are more than brutes. Our disorders indicate that we are far more complicated than creatures of instinct. Our misery and anxiety are crucial evidence of our souls, Tocqueville thinks, and the need for transcendence. But to avoid misery we seek diversions. We direct ourselves away from the crucial needs of our souls. Such restlessness when continuously ignored becomes difficult to live with. Is freedom worth it? Recall that for Tocqueville, liberty requires faith in human greatness and prideful action, both necessary to preserve dominion over our lives. Paradoxically, it is what he calls "individualism" that must be opposed in the name of prideful individuality, because the former reduces us, first to the small circle of family and friends, then to passive beings unable to act on behalf of our need to know the truth about ourselves. Individualism eventually reduces us to a condition of indistinguishable blots within a cosmic whole.

The exercise of freedom and attempts at human greatness would cease to matter as we would no longer actually believe in the worthiness of our personhood. Tocqueville labels this "pantheism," and he greatly fears its workings in democracy because, in losing the distinctive aspects of our human existence, we come to see ourselves as mere pawns of grand historical forces. The practical result of such passivity is dependence on a government that grows softly despotic and an absence of social concern for others. The great fear of Tocqueville was that "in the dawning centuries of democracy individual independence and local liberties will always be the products of art" but "[c]entralized government will be the natural thing." How are we to maintain the spirit of liberty against the viral spread of enervating equality, which reduces and isolates individuals from one another?

The individualism that Tocqueville fears, and the dogmatic liberalism it underwrites, leaves us rootless. This background permits us another position from which to understand the resonance of Deneen's claims about liberalism. David Goldman put this well in a December 2017 essay in Standpoint called "The West Must Restore a Sense of the Sacred." He remarked that we in the postmodern West are seemingly bereft of our past, and equally unable to envision our future. We sense that existence itself might end with us because we are unable to transcend the giant suck of individualism. This is also a consequence of the rise of bland secularism as the all-embracing perspective of our elites and most of our public institutions. To notice this is not to call for the law of God to be forced into the public realm. It is only to note, with French theorist Rémi Brague, that secularism reduces our memories and limits our hope and confidence in striving to shape the future with essential human goods — most notably that of family, but also a willingness to sacrifice in general.

One likely outcome of such thinking, as Peter Lawler observed, is that Being itself is entirely associated with my being. We become unable to give, to love, to die well because we can dimly see the transcendent worth of such acts. Even to wait for death by natural causes may involve too much patience, senseless suffering, and so may simply not be worth it. If such thinking is the norm, then this will mean we can and must invent our own identity. But this is where Tocqueville underestimated the sturdiness of relational human nature, and where Deneen overestimates the power of an emancipatory liberalism to supplant our need to flourish as social and relational beings.

The components of our politics thus behave as opponents, gripped by irrational forces, groping for identity and meaning in an environment where many of the old sureties are gone. For many Americans, the strenuous aspects of their professional, familial, religious, and political lives are the results of the novelty and uncertainty of our situation. Working in the gig economy, or in an endless rotation of service-sector employment with little opportunity for real income advancement, leaves even the heartiest of workers dissatisfied and downcast at some point. Family life, as a consequence both of such employment and of pathological behaviors, is for too many Americans anything but a refuge of love and sturdiness from a hard world. And for many Americans, religion as an institutional practice appears increasingly irrelevant, and our houses of worship seem flat-footed in the face of congregational downsizing. As other observers have noted, this diminishment of faith and religious belonging may explain very well the poisonous and overheated political environment we now inhabit. The quest for meaning has been displaced.

All of the foregoing will lead to attempts to form new identities. Even if we conceive of ourselves as autonomous projects, this will inherently involve public and collective impositions. Underneath these appearances, though, lurks something else. Is there a better understanding of current miseries? Might we be contending with what Goldman terms a "struggle with the sacred"?

Our ailments are signs of what is lacking in our lives, and of the kinds of efforts that we should take up. The term "sacred" is employed by Goldman to mean "that which endures beyond our lifetime and beyond the lifetime of our children, the enduring characteristics that make us unique and will continue to distinguish us from the other peoples of the world, and which cannot be violated without destroying our sense of who we are." It follows from this immemorial need that we must protect the sacred, which means we must recapture the past and use its ballast to orient our future conduct. For that, you need a nation, Goldman observes, to embody the customs, language, and ethos that have shaped you as a people.

How then to recover the sacred in Western democracies? This is the question we are ultimately led to in confusion. But the sacred is also a challenge to liberal democracy and its flatness, its collapsing of our horizons to just us chickens or what the theorists refer to as "rational self-interested players." The question Goldman posits is whether the liberal tradition actually inspires us to act beyond our self-interest. We do need more than liberal theory to keep liberal democracy thriving. This is particularly true if we are to continue being willing to sacrifice for our country and carry its burdens — which is imperative, for in so doing, we forge the bonds of mutual loyalty.

Such devotion is not just about military service. It's about family and community formation too. Liberal democracy purely on its own reveals its existential weaknesses in the increasing refusal of its denizens to have children. A secular liberalism seems to struggle to make sense of children and family and the demands they place on us. Ultimately, the best answer is that we need a sense of the sacred illuminating the collective existence of citizens.

But to acknowledge the need for a sense of the sacred is not to reject or to criticize liberalism. It is to argue for a certain kind of liberalism over another. Goldman posits that the sacred in America is inherently defined by individual redemption, as best set forth in John Bunyan's Pilgrim's Progress. Or as Tocqueville observes in Democracy in America, resort to our Puritan origins can best illuminate our responsibilities as citizens who believe in the equal worth of every individual before the law, because the Puritans first believed that we are all equally created by God. The rights of our Declaration are best defended — because they are made real to us — not by the god of the philosophers but by the providential, personal, and loving God of Puritan faith, whose legacy even today haunts our democratic souls. In the popular mind, we connect with this belief through hard and tough men like Huck Finn, John Wayne's cinematic cowboys, and Clint Eastwood's detectives. They all derive from belief, Goldman says, in the American understanding of our pilgrim predecessors. Our commitment is not only to redemption in this telling, but also to renewing corrupt institutions and saving the lost and the innocent from bad men.

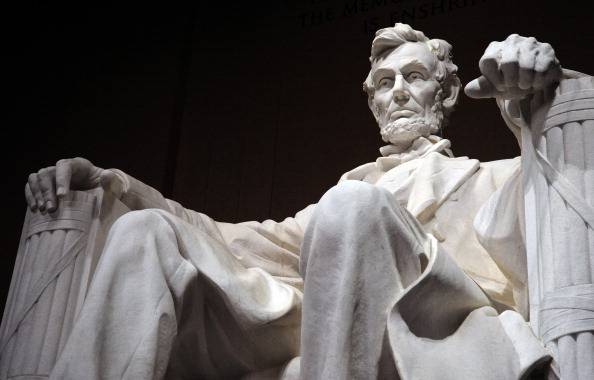

A FORTRESS OF STRENGTH

Other deep students of America have seen this too. Abraham Lincoln pointed in this direction in 1838 when, at the age of 28, he delivered an extraordinary speech on "The Perpetuation of Our Political Institutions" to the Young Men's Lyceum of Springfield, Illinois. Lincoln's aim, in this perpetuation, was to respond to the waning of the revolutionary founding spirit in America by rebuilding our country "with other pillars, hewn from the solid quarry of sober reason." Those pillars will be built by a new reverence for the Constitution and the laws, which is needed because the founding memories and passions have faded.

Lincoln's almost disturbing turn to political religion purports to be inspired by instances of mob justice and lynchings that he claims were overwhelming the country with lawlessness. This, however, is really a cultivated set-up by Lincoln. The United States was not really facing a widespread rise of mob violence threatening the very notion of the rule of law. Lincoln even notes, in a nod to his audience's likely sympathy with the mobs' actions, that most of the lynched men he mentions were not really worthy of our pity. The trouble was not a few isolated incidents of violence, but a broader openness to such violence. His point is that lawlessness in spirit leads to lawlessness in practice. The country suffers irrevocably when its patriots abide and witness such behavior, which fractures their own attachments to the country.

Lincoln's purpose is to provide a deeper justification of how we maintain our devotion to the country, its laws, and its order. The object of the passion and pride of citizens must be the nation. The problem, Lincoln says, is that the founders fought to demonstrate the truth of a proposition, that men are capable of self-government. He wonders if we still believe this proposition to be true. Lincoln's formulation is not inspiring: "[T]he game is caught; and I believe it is true, that with the catching, end the pleasures of the chase." We're dealing with the proposition of self-government — how could the game ever be caught? This seems to be a rather strange way to argue that the American founding on its own terms no longer inspires us sufficiently to protect it. This means, Lincoln argues, that when the men of unmeasured ambition rise among us, seeking to be founders of a new order, we might be unable to prevent them from ruling. And Lincoln is not in doubt on this matter, as he says:

[N]ew reapers will arise, and they, too, will seek a field. It is to deny, what the history of the world tells us is true, to suppose that men of ambition and talents will not continue to spring up amongst us. And, when they do, they will as naturally seek the gratification of their ruling passion, as others have so done before them. The question then, is, can that gratification be found in supporting and maintaining an edifice that has been erected by others? Most certainly it cannot.

These men, Lincoln notes, will disdain the limited realm of government that our Constitution sets forth. How will we contain their regime-destroying egos?

His first answer is conclusory: "[I]t will require the people to be united with each other, attached to the government and laws...to successfully frustrate his designs." But how? Recall Lincoln's earlier use of the term "proposition" to refer to the founders' work. Propositions must be demonstrated, but the very nature of our fathers' proposition is self-government. Their demonstration no longer inspires and recruits our sentiments to noble deeds. Scenes from the founding no longer resonate with the living, Lincoln observes. The tide has gone out on their deeds: "They were a fortress of strength; but, what invading foemen could never do, the silent artillery of time has done; the leveling of its walls." The founding memories fail because the living monuments to them are brought down by the "all-resistless hurricane" of time. But more important, Lincoln notes, we came to believe in the significance of those events through passion, and passions subside.

Lincoln's theme, also present in the Gettysburg Address, is a muted or implied criticism of the founders' political work, not because they failed, but because the terms of their achievement do not invite full-throated devotion. They were too rationalistic in their own understanding of what they were accomplishing. They appealed to social-contract theory and common-law grievances to explain their act of separation from Great Britain. The Constitution opens with a mere restatement of the classic five-fold ends of government in the Preamble to enlist us in the work of self-government for "ourselves and our Posterity." Sound doctrine, but is it worthy of devotion across the generations?

A quarter-century after his speech to those young men in Springfield, in the course of numerous speeches to a nation on the brink of war and past that brink, Lincoln supplied the founding with biblical imagery and scriptural cadences to stir citizens to the work of securing the Union and continuing our constitutional form of government even through immense sacrifice. Daniel Dreisbach notes that the Gettysburg Address "contains no direct biblical quotations; however, there are few clauses that do not echo the cadences, phrases, and themes of the King James Bible." One prominent theme is sacrifice, he notes:

The soldiers memorialized in Lincoln's oration, like Jesus Christ, "gave their lives," in Lincoln's words, so others "might live." The nation, Lincoln pointedly observed in the opening clause, was born on July 4, 1776; it was reborn in Gettysburg eighty-seven years later to the day, after having descended into hell for three days of battle, carnage, and death.

Lincoln calls for a sacred American tradition. He understood the principles of our liberalism better than any of our statesmen, but he also understood that our liberalism was more than these cold principles, and much more than individualism.

ON PENALTY OF DECADENCE

Lincoln concludes the Lyceum Address by noting that the founders' "pillars of the temple of liberty" had "crumbled away." It was now up to a new generation to reinforce them, and without resort to the intense passions of war and revolution. "Reason, cold, calculating, unimpassioned reason, must furnish all the materials for our future support and defence." He does not call for the reason of the philosophers, however. The next sentence states that this reason must be "moulded into...a reverence for the constitution." Our reason is both a starting point and a basis for transcendence to the high calling of upholding our constitutional liberty. Reason provides us with material for assenting to the proposition, but reason points beyond itself, inviting us to deeds it can't explain on its own terms.

That is why we aren't only revering the Constitution, Lincoln finally intones. Our reverence is made with a spirit of dedication to our nation's first father. "[T]hat we revered his name to the last; that, during his long sleep, we permitted no hostile foot to pass over or desecrate his resting place; shall be that which to learn the last trump shall awaken our WASHINGTON." If we do this well, then it will be with our country as with the Christian church, "the only greater institution," and "the gates of hell shall not prevail against it."

Lincoln knew what our liberals do not, that while government and church are two separate spheres with different ends, free government calls forth our loyalty and our virtue too, shaping both in the course of its reign in our lives. We become a certain kind of person in the political order we inhabit, and a constitutional order requires a profound, liberal outpouring of duty. Thus our love for our country and our actions taken to support it shape our existence, individually and collectively.

Free government requires self-limitation, judgment, prudence, and courage if it is to flourish. While self-interest will be our steady pursuit — facilitated by our institutions — the significant challenge is to remain in argument with those we disagree with, and to do so for the best result for our country. We are not engaged in a war with fellow citizens who disagree with us. We are engaged in debate, compromise, and limitation, performed with great respect for our institutions, aware that they must outlast our moment on the political stage.

John Courtney Murray's timeless 1960 work, We Hold These Truths, further enlists and builds on our dedication to the American proposition. Lincoln's arguments, his reasoning, and his innovative statesmanship, Murray notes, became "classic American doctrine." Murray highlighted Lincoln's use of the term "proposition," noting that the American proposition is never finished, "[n]either as a doctrine nor as a project," and we must continue its "development on penalty of decadence."

Murray was a Jesuit priest, and yet we do not see in his work the same resort to religious language or the rhetoric of the Bible in speaking of the American proposition. But Murray's proposition, it should be said, is also not an Enlightenment formula of natural rights or a compact statement of the limited aims of artificial or contrived government. His confidence — a philosophical, legal, and historical confidence — is in the ancient nature of the Constitution, rooted in the English constitutional tradition. That also means, Murray says, that it's built on natural law and philosophic realism. We are able to know the truth about ourselves, and we have the confidence to understand what is required of us to uphold republican constitutional government. And that means our constitutional order, its laws and discourse, while surely guided by interests, myths, legends, and prejudices, reflects a civil bond built on reason. If we deny that reason, Murray notes, the American proposition will be "eviscerated at one stroke."

We might ask what all of this really amounts to. Perhaps we could just work directly from the texts of the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, the Federalist Papers, and other seminal sources to get square with our American constitutional tradition and recover its excellence in our own time. But Murray identified a basic problem: Are we still capable of believing in the American proposition? To be sure, the phrase is Murray's, but it builds on Lincoln's insistence on the truth of human equality under God and its becoming the architectonic truth of the American order. For Lincoln, this manifested in the obvious problem of overcoming slavery.

Murray's different problem is rooted in both the skepticism of the modern mind and its complacency about the ground of truth upon which a republican constitutional regime must rest. He wants to rehabilitate the American proposition, rooted "in the fact that the American political community was organized in an era when the tradition of natural law and natural rights was still vigorous. Claiming no sanction other than its appeal to free minds, it still commanded universal acceptance. And it furnished the basic materials for the American consensus." As Murray more succinctly stated things: "There are truths, and we hold them, and we here lay them down as the basis and inspiration of the American project, this constitutional commonwealth."

But is Murray's project now exhausted? It is doubtless severely constrained by our near inability to think in philosophically realistic terms about who we are as a people. Beyond the philosophical skepticism Murray had to confront, we are now loaded with racial, gender, and class denunciations of the founding. Our constitutional founding appears even more distant in the postmodern rearview mirror; as President Obama would intone, it's where we're going as a people that matters, not the past.

But Obama and his fellow progressives do not sit on some privileged side of history; they have no secret insights into the future of this republican people.

RENEWING THE PROPOSITION

So what does it now mean to invoke and develop the American proposition? It cannot mean repeating the words of the founders without thought to their context and to our own. Their principles are sound, but we are met, as they were, with new challenges to self-government and with the omnipresent threats of license, apathy, and soft despotism. In our time, these challenges present themselves in the very structure and function of our institutions — including and especially those created by the Constitution.

We have seen these institutions evolve away from an emphasis on debate and discussion and toward both technocratic expertise and judicial fiat. Conservatives tend increasingly to be better at resisting the former than the latter. The lure of rule by judges has grown on the right, because we have been losing our grasp on the character and purpose of self-government.

Instead of insisting that the Constitution is almost solely a fixed policy document, with its fasteners announced by the judiciary, we should engage in the ongoing quest for self-government, one that cannot be perfected nor anchored in certainty. Our future can be anchored only in the manners and morals of the people, which may or may not reflect what are the crucial philosophical suppositions of the Constitution: skepticism of power, limited government, the rule of law, and a desire to bring order to our liberty as self-governing men and women who give ongoing or recurring consent to the laws that are passed. If we lose these habits and commitments, then our Constitution's meaning will change and will reflect the new ways of thinking and living that we as a self-governing people forge. No theory of empowered, engaged, or activist judges will change that. Only the habits of self-government can, and those habits must be built by practice in deliberation — even about the Constitution.

To better grasp this point, we should consider the notion, expressed in Federalist Papers Nos. 37, 78, and 82, of "liquidating" the meaning of the provisions of the Constitution. This idea arises in Publius's reflections about how to make clear the elements of the Constitution that are apt to be contested. The discussion in Federalist No. 37 is most pertinent for our distressing situation. It is there that Publius discourses on the difficulty of ascertaining the boundary between federal and state powers. He states,

Here, then, are three sources of vague and incorrect definitions; indistinctness of the object, imperfection of the organ of conception, inadequateness of the vehicle of ideas. Any one of these must produce a certain degree of obscurity. The convention, in delineating the boundary between the federal and State jurisdictions, must have experienced the full effect of them all.

Elsewhere in that essay, Publius notes, "All new laws, though penned with the greatest technical skill, and passed on the fullest and most mature deliberation, are considered as more or less obscure and equivocal until their meaning be liquidated and ascertained by a series of particular discussions."

How then does one engage in the process of liquidation? We should turn to James Madison for a practical answer. Madison applied his version of originalism to parts of the Constitution that were fluid and uncertain. He opposed the creation of a national bank as unconstitutional when it was first proposed in 1791. He thought there was no possible reading of the Constitution that could support it. But with the passing of a generation, he no longer insisted upon his constitutional position, even when he did maintain an objection on policy grounds to the creation of the Second National Bank. What is telling is that Madison never changed his underlying opposition to the constitutionality of a bank. He stated in his "Veto Message on the National Bank," on January 30, 1815, that raising a constitutional objection to the Bank was "precluded in my judgment by repeated recognitions under varied circumstances of the validity of such an institution in acts of the legislative, executive, and judicial branches of the Government, accompanied by indications, in different modes, of a concurrence of the general will of the nation."

That is, Madison never wavered on the bank's constitutional validity in his own reading of the Constitution. The crucial distinction, which he demonstrates in correspondence with Nicholas Trist in 1831, is between expounding and altering the Constitution. This means that the Constitution can be expounded by sustained republican practice, one that made such exposition authoritative. As he states to Trist,

On the subject of the Bank alone is there a color for the charge of mutability on a Constitutional question. But here the inconsistency is apparent, not real, since the change, was in conformity to an early and unchanged opinion, that in the case of a Constitution as of a law, a course of authoritative, deliberate, and continued decisions, such as the Bank could plead, was an evidence of the public judgment, necessarily superseding individual opinions.

This passage evinces Madison's view that the national bank was unconstitutional but that republican judgments issued by the legislature had expounded the Constitution and legitimated the bank.

Another letter of Madison's, this one to Charles Ingersoll, also in 1831, distinguishes between the higher law of the Constitution and the subordinate laws promulgated by the legislature:

A Constitution being derived from a superior authority, is to be expounded & obeyed, not controuled or varied by the subordinate authority of a legislature. A law on the other hand, resting on no higher authority than that possessed by every successive legislature, its expediency as well as its meaning is within the scope of the latter.

Madison states that the legislature obeys and expounds the Constitution. But this constitutional liquidation isn't an arbitrary process that simply sets constitutional meaning according to the whims of the living generation. The question he raises is whether the legislature's precedents that expound the Constitution can guide succeeding legislatures and require that individual opinions be put aside after a time. Madison compares this process to judicial precedent, which has the effect of settling the meaning of a law passed by the legislature. Such decisions make the meaning of the law known and certain, which would not be the case if every judge could change the law's meaning in the particular cases he hears according to his whims.

Precedent also gives authority to the law "because an exposition of the law publicly made, and repeatedly confirmed by the constituted authority, carries with it, by fair inference, the sanction of those, who having made the law through their legislative organ, appear under such circumstances to have determined its meaning through their Judiciary organ."

But the Constitution's meaning must also become "fixed and known." While the subordinate law of statutes is settled by judicial rulings, the higher law of the Constitution is entrusted to the legislature. So when it comes to constitutional exposition as opposed to statutory exposition, Madison in the same letter turns to lawmakers and not judges. It is the former who perform the crucial work of expounding. They are unable to act on "solitary opinions...in opposition to a construction reduced to practice, during a reasonable period of time." Madison's originalism is a constitutionalism that is inter-generational: The people provide their sanction to it by acting through all three branches, and it's about exposition without altering meaning, such that further exposition is expected in time. This is a constitutionalism without one fixed meaning, but it is also a constitutionalism which requires great force to move it.

The opposite is the judicial-led constitutionalism that currently leads us by the nose. Its greatest deficiency is what Madison rejected: that controversies can be decided by "a will in the community independent of the majority that is, of the society itself." The independent will is "a power independent of the society [and] may as well espouse the unjust views of the major, as the rightful interests of the minor party, and may possibly be turned against both parties."

What we must consider, then, is the case for a different kind of originalism. Public debate is how we reach "the cool and deliberate sense of the community." As Willmoore Kendall observes,

[A]s disciples of Publius, what we should want above all is that the relevant questions shall be decided by the "deliberate sense of the community" — and the deliberate sense of the community [is] not about the intent of the Founders (it was, above all, that we should govern ourselves, and so prove to mankind that self-government is possible)...but about the merits of the competing policy alternatives amongst which we, as a self-governing people, are obliged to choose. Which is to say: about the appropriateness of competing policies to our conception of ourselves as a people, to our historic destiny as we understand it, to our settled views as to the nature of the good society.

Progressives have looked to the Court to pave a constitutional path of egalitarianism and emancipation that eagerly departs from the text, believing, as they do, that they stand atop history and understand its architectonic flow. But are conservatives, perhaps unintentionally, further enthroning the judiciary, putting our own elites on the bench, to chart our preferred course back to the founders?

In short, we play a game of elites by relying on a few men and women in black robes. But with respect to the republican foundation of the Constitution and with regard to our long-term interests as those who value limited government, this is not the best play. Putting authority to decide the meaning of the Constitution into the hands of the self-governing people is the superior move.

OUR MORE THAN LIBERAL INHERITANCE

This takes us back to liberalism, at its best. By working to breathe life back into an American liberalism that is more fully in contact with its pre-liberal sources, we can escape the kind of postmodern liberalism that Patrick Deneen rightly rejects — but also recover the kind of modern liberalism that offers us our only sustainable alternative.

Today's critics of liberalism are not wrong to impugn what has become of it, and to mourn what that has cost us. But they are wrong to abide, let alone to celebrate, the demise of our way of life. What awaits us after liberalism is not some integrated pre-liberal moral order but the chaos of a society unmoored from its foundations and from the standard of flourishing that those foundations provide.

Rather than cursing our inheritance, we should appreciate that its worst facets are not its essence. Rather than accept a liberalism distorted by the abuses of progressivism as the only liberalism we can have, we should stir ourselves to recover and revive its proper forms — and so to combine once again reason, passion, and a sense of the sacred for the sake of a proposition that remains today, as ever, a statement of the deepest kind of truth.