Getting Ahead in America

America's familiar debate over income inequality conceals and confuses at least as much as it reveals. To hear most journalists and activists tell the story, our country is the scene of a rampant and long-running economic travesty, as the rich grow richer, the poor grow poorer, and the distance between them belies the promise of America even in times of prosperity. As President Barack Obama put it during his 2008 campaign: "While some have prospered beyond imagination in this global economy, middle-class Americans as well as those working hard to become middle class are seeing the American Dream slip further and further away."

Such arguments are generally marshaled in the cause of expanding social-welfare programs aimed at transferring wealth from the rich to the poor, thereby combating both poverty and inequality. Opponents of such programs have usually not engaged the inequality argument directly, instead contending against the growth of government or pointing to the failure of some welfare programs to achieve their stated aims.

But in so arguing, both sides too often miss the point. Those enraged by inequality tend to be careless with their statistics, often painting a distorted picture of American life. Their opponents have accepted these false premises, rejecting only the solutions the outraged wish to pursue. Both sides ignore the real threat to the American Dream.

That dream, after all, is not about economic equality, but about opportunity and upward mobility about getting ahead. And for those at the bottom in our society, the challenge of getting ahead is daunting and complicated. The rich are not the reason that the poor are poor, and the real reasons — which have to do not only with economics but also with culture, history, and especially individual behavior and personal choices — add up to an enormous problem that deserves to stand front and center in our politics. As we have learned over decades of trying, it is a problem that does not lend itself to easy policy solutions. But seeing more clearly just how the question of mobility does and does not relate to the equality debate may clarify both the potential and the limits of policy and politics in helping the poor get ahead.

UNDERSTANDING INEQUALITY

On its face, the common tale of economic inequality in America seems clear and simple. For the past quarter-century, household income has grown substantially for upper-income families, modestly for middle-income families, and even more modestly, if at all, for low-income families.

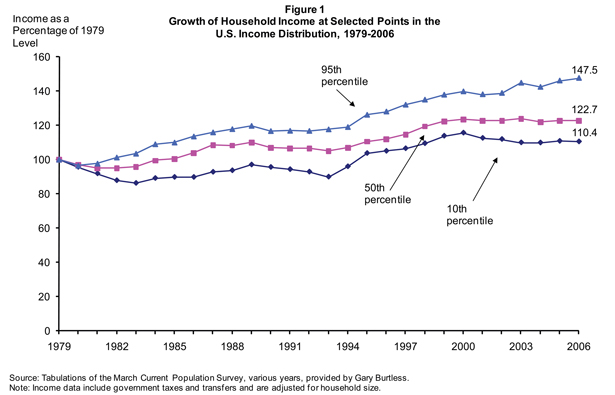

Figure 1 compares the trends in size-adjusted household incomes at the 95th, the 50th, and the tenth percentiles between 1979 and 2006. To emphasize trends, incomes are expressed as percentage changes each year relative to 1979 (a peak year in the business cycle) using inflation-adjusted dollars. The figure shows that those at the tenth percentile increased their income by a paltry 10% over the last quarter-century (even after government benefits); those in the middle increased their income by nearly 25%; and those at the 95th percentile enjoyed a growth of nearly 50%. Further data not shown in the graph leave no doubt that if we moved above the 95th percentile, the percentage growth in income would rise rapidly. In his popular 2007 book Richistan, Robert Frank reports that by 2004 the top 1% of Americans earned around $1.35 trillion a year — a figure greater than the total national incomes of France, Italy, or Germany.

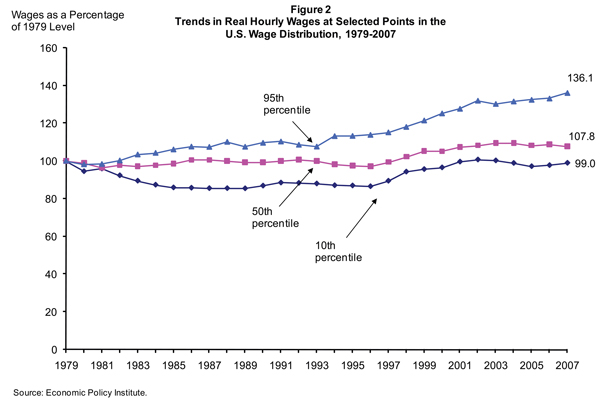

Now consider wage growth. Earnings are the major source of income in most households, and income from earnings is determined in large part by wages. Figure 2 shows the trends in real hourly wages since 1979, using the same percentage-change approach as Figure 1. The tenth percentile declined and then rose, but ended up slightly below its starting point a quarter-century earlier. The middle ended up about 8% above its 1979 starting point, and the top soared by more than 35% over the same period.

These results seem to present a straightforward tale of exploding incomes and wages at the top, and struggle and stagnation at the bottom. But the full story is far less simple, as these common measures of inequality overlook several important considerations.

The first is spending on health care. As shown by my Brookings Institution colleagues Gary Burtless and Pavel Svaton, medical spending as a share of personal income averaged across all Americans jumped from 7% in 1960 to 21% in 2007. If medical care were paid for out of the pockets of health-care consumers, the huge growth in health spending would have little or no bearing on income inequality, since it would come out of personal income. But about 75% of spending on health care comes from sources other than personal income, namely private insurance mostly paid for by employers and government payments made by Medicaid and Medicare. In other words, one of the biggest single sources of consumer spending by families — and one that is growing rapidly each year — is ignored in most inequality calculations. This approach to inequality is roughly equivalent to estimating the size of a city by counting the names in the phone book, but ignoring all names that begin with "R," "S," and "T."

What if we included spending on health care paid for by third parties in our inequality calculations? Burtless and Svaton used data from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey to explore this question. Averaged over the 2001-2005 period, per-person spending on health care for those under age 65 in the bottom fifth of income was greater than per-person spending on health care for those in the second and middle fifths. It was only slightly below spending by those in the two richest fifths. For those over age 65, whose needs for health care are much greater than the needs of younger people, per-person spending was higher in the bottom fifth than in any other.

How is it possible that people with so little income could spend so much on health care? The answer, as we have seen, is that most of the payments for health care are made by third parties. Indeed, people under age 65 in the bottom 10% of earners enjoyed third-party payments on health care equal to 65% of their income. People in the second tenth enjoyed third-party payments equal to 21% of their income. By contrast, people in the top two income tenths had third-party payments equal to 3% and 2% of their income, respectively. For those over age 65, people in the bottom fifth enjoyed third-party payments equal to an amazing 130% of their income, while those in the top fifth enjoyed payments equal to only 6% of their income.

If the cost of health care paid for by third parties were included in the calculation of income, in percentage terms the incomes of families at the bottom of the distribution would get a much bigger boost than incomes at the top of the distribution. It follows that inequality would fall.

These figures say a lot about the American health-care system, which certainly has its problems. But government programs — which cover nearly everyone over age 65 and a considerable share of those living in poverty (including all poor children) — nearly equalize per-person spending on health care across the income spectrum. This is a dramatic, albeit expensive, achievement of American social policy. But the typical account of growing income inequality ignores almost all of this spending.

A second omission in the standard story of income inequality has to do with the limits of the most commonly cited data on the subject. Most articles on income inequality that appear in professional journals and the media are based on the Census Bureau's Current Population Survey. But as Cornell economist Richard Burkhauser has shown, this CPS data has serious problems.

To protect the identities of very high-income participants in the survey, their incomes — estimated in 24 categories, including earnings, investments, capital gains, business income, and gifts — are top-coded. Under this procedure, income above the top-code level in all 24 categories is scored as equal to the top-code, which leads to a flawed view of income growth at the top of the distribution. This is especially true when one considers that all analysts who have studied changes in income over the past several decades agree that the big increases take place at the top. If this growth is poorly measured, calculations of income inequality over time are bound to be unreliable.

Burkhauser and his colleagues gained access to special data from the Census Bureau not generally available to researchers; they also developed sophisticated statistical techniques to construct a data set that provides an accurate portrayal of income over the entire distribution for the years between 1975 and 2005. This more accurate data set yields results that would be quite surprising to the editors of the New York Times, who routinely rail against the rising income inequality shown by CPS data.

A standard measure of inequality employed by Burkhauser and many other researchers is the ratio of income at the 90th percentile of the income distribution to income at the tenth percentile. If this ratio rises over time, we can conclude that inequality has increased. Burkhauser finds that the 90 / 10 measure of inequality increased nearly 25% during the 1980s, declined by 7% during the 1990s, and was more or less flat in the first five years of the 2000s. By another standard measure of income — the Gini coefficient that measures changes along the entire income distribution — income inequality increased by about 15% in the 1980s, fell by over 2% in the 1990s, and held steady between 2000 and 2005.

An especially notable feature of Burkhauser's work — and one that many inequality researchers have yet to acknowledge — is that, since about 1990, the entire income distribution has shifted up. In other words, incomes all along the distribution, including the bottom, grew. If Burkhauser is correct — and no one has yet shown his improved data to be flawed — claims about increased income inequality since 1990 based on the CPS are exaggerated.

Relative changes in the prices paid for consumer goods by the poor and rich provide yet a third caveat to the standard inequality story. Consumption is a more direct measure of well-being than income: A family with a modest income might use some of it to purchase jewelry and lottery tickets, while another family with the same income buys food, makes a house payment, and saves a little. Judging solely on the basis of income would lead us to believe that the two families are equally well off. But examining the consumption patterns of the two families produces a different picture.

Christian Broda and John Romalis of the University of Chicago have shown that the prices of goods purchased by the poor have increased much more slowly than the prices of goods purchased by the rich (and, in some cases, have even fallen). Using data on purchases of food, durable goods, and nearly every other consumer item by a representative sample of American households, Broda and Romalis found that, between 1994 and 2005, the consumer basket-adjusted income of households at the tenth percentile increased 18%, while adjusted income at the 90th percentile increased 17%. They show similar results for food purchased away from home.

Broda and Romalis estimate that 20% of the relatively inexpensive consumer items purchased by the bottom fifth of households (often at big-box stores like Wal-Mart) come from China, while only 5% of such items purchased by households in the top income fifth do. Free trade does a lot to compensate for the growth in inequality caused by trends in wages and incomes, and goods from China play an especially important role in helping the poor enjoy a higher standard of living than they would if their choices in consumer goods were more restricted. Broda and his colleague David Weinstein show, for example, that the types of consumer goods increasingly imported from China exhibit steeper price declines, and that the poor purchase more of these goods. As a result, consumer goods from China — and the free trade that brings them to the United States — help poor households more than rich households.

The seemingly straightforward story of income inequality therefore turns out not to be so simple. It is a tale of subtle hues, not stark contrasts, and some of the most basic claims thrown around in the media turn out to be rather dubious.

This does not mean that inequality has not been growing, or is unimportant. But it does suggest that our approach to the plight of the poor ought not to be rooted in the familiar story of inequality — as that story is not entirely accurate, and is not the most important facet of poverty and opportunity in America. Whatever the relative position of the poor in America compared to the wealthy, their plight should draw our attention on its own terms. Whether their situation improves as quickly as that of the wealthy or not, we ought to find policies that enable those at the bottom to rise. Unfortunately, the inequality debate is more often a distraction from that challenge than an appropriate path toward

solving it.

GETTING AHEAD

Polls show that when it comes to measuring fairness, income inequality has long been less important to the American public than economic mobility. What matters is not how you compare to others, but whether you have a chance to improve your own circumstances.

Using a powerful data set built by researchers at the University of Michigan over more than four decades, my Brookings colleagues Isabel Sawhill and Julia Isaacs and I have examined American economic mobility in great detail. The Michigan data set includes mostly annual data on employment, income, family composition, education, and many other measures of a set of 5,000 families who have been participating over the entire four decades. As they left home and formed their own families, children of the original 5,000 families were followed through childhood and into adulthood. Most of the analyses of income mobility compared the incomes of nearly 2,400 individuals who were younger than 18 in 1968 with the incomes of their parents. The average age of parents was about 41 at the time the income data was collected; adult children ranged in age from 27 to 52. All incomes are adjusted for inflation and expressed in 2006 dollars.

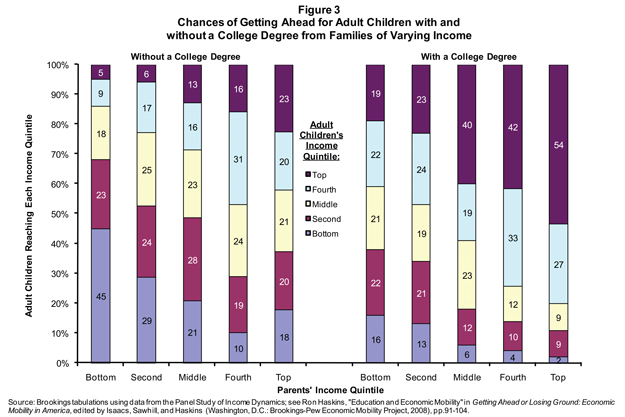

Figure 3 shows the income of the parent generation divided into five groups of equal size from lowest to highest on the horizontal axis of the figure. The sections within each set of bar graphs provide the income levels achieved by the children of parents in each fifth of the income scale. The set of five bar graphs on the left is for children who did not earn a four-year college degree; the set on the right is for those who did.

The figure illustrates several of the most salient characteristics of income mobility in America. Even among those without a college degree, we see considerable movement between income fifths. Nearly 30% of children from families in the middle fifth moved up to the fourth or top fifths as adults. About one-quarter of them stayed in the middle fifth, but the remaining half fell to the bottom two fifths.

The bar graphs that show the fortunes of those who obtained a four-year degree reveal perhaps the most important generalization to emerge from this analysis of mobility: The effects of a college education are pervasive, regardless of family background. Children from the bottom fifth can greatly increase their chances of making it out of the bottom as adults — from 55% to 84% — if they obtain a four-year degree. Similarly, with a degree they can nearly quadruple — from 5% to 19% — their chances of making it all the way to the top fifth. A college degree is equally powerful for those at the top: 75% of children from the next-to-the-top fifth, and 81% of children from the top fifth, can stay in the top two fifths as adults by obtaining a college degree. If they don't get a college degree, their chances of remaining in the top two fifths plummet to 47% and 43% respectively.

These striking findings on the effects of a college degree — combined with the fact that the federal government, state governments, and the private sector provide generous support for student aid for the disadvantaged (totaling about $162 billion in grants, loans, and tax breaks in 2008) — illustrate the best approach to boosting opportunity: personal effort, bolstered by public and private support.

These data lead to the conclusion that mobility is alive and well in America. Although family background continues to exert a powerful influence, there is considerable movement both up and down the income distribution. Even more to the point for our purposes, individuals can greatly influence where they wind up by working hard and getting a college degree. A vital characteristic of mobility in America is that effort pays.

But there is still room for improvement. Compared to other countries, for instance, mobility in America is surprisingly low. Americans tend to think they have more opportunity and mobility than citizens of other nations: As shown by the International Social Survey Program conducted in 27 countries between 1998 and 2001, Americans believe more than the citizens of most other countries that they are rewarded for effort, that family background is not a major barrier to mobility, that income inequality is not too large, and that individuals rather than governments bear the major responsibility for reducing differences in income. But the American belief that opportunity is greatest in the United States is out of line with the facts.

Miles Corak of the University of Ottawa surveyed all published studies of international comparisons of father-son income correlations and determined that the highest correlations were found in the United States and the United Kingdom. France, Germany, and Sweden were a step below, while Canada, Finland, Norway, and Denmark had still smaller correlations. All four countries in this last group had a father-son income correlation well less than half the level of the U.S. and U.K. If the incomes of sons are more similar to those of their fathers in the U.S. than in other industrialized countries, the implication is that we have less rather than more economic mobility. The apple is falling closer to the tree in America than in other nations.

Markus Jäntti and his colleagues from Finland's Abo Akademi University replicated Corak's findings, using data from the U.S., Finland, Norway, Sweden, and the U.K. The team also came across a discovery that gives pause to anyone concerned with the income mobility of poor males in the United States. Across all nations, there was a tendency for correlations to be "sticky" at the top and bottom. In other words, father-son income correlations tend to be higher between rich fathers and their sons, and between poor fathers and their sons, than they are between fathers and sons in the middle of the income distribution. But the stickiness was stickier in the U.S. : Young American men from families in the bottom fifth of income had a greater likelihood (42%) of ending up in the bottom fifth themselves than did males from the five European nations (between 25 and 30%). Similarly, whereas only 8% of U.S. males from the bottom made it all the way to the top, males in the European nations had an 11 to 14% chance of reaching the top.

The quality and breadth of these studies, plus the consistency of findings, lead to the conclusion that the U.S. has less income mobility than other industrialized nations. Nonetheless, America is the world's leading destination for opportunity-seeking immigrants. For over a decade, around 1.5 million immigrants have entered the U.S. each year, perhaps a third of them illegally. The home countries of these immigrants have shifted from primarily European to primarily South American and Asian nations over the past several decades. Simultaneously, the number of immigrants with less education than the average American has increased substantially. Thus, although many immigrants with advanced degrees and highly marketable skills come to the U.S., the average wage of immigrants relative to the average wage of native workers has been declining for more than half a century. Economists disagree about whether poorly educated immigrants have an impact on the wages of native workers at the bottom of the distribution; they do not disagree, however, that immigrants with less education greatly increase their economic mobility by coming to the United States.

In fact, as Robert Lerman of the Urban Institute has shown, the openness of America's borders tends to promote the economic mobility of immigrants while reducing summary measures of economic mobility for America as a whole. It is easy enough to see why. Consider an immigrant from Mexico with a fifth-grade education. If he stays in Mexico, he might earn the equivalent of $3,000 to $4,000 a year (if he can even find a job). But in the U.S. he can easily find a job that pays $9 per hour and work full-time to earn around $19,000 a year. In the surveys used to measure income mobility in the U.S., the amount he could earn or actually did earn in Mexico is not included in the calculation, but his low wage working in the United States is. And because there are so many others like this immigrant, as Lerman shows convincingly, measures of U.S. economic mobility would be boosted if their actual or potential income in Mexico were included in the calculation. American citizens might not be impressed by this argument, but America certainly provides great opportunity for the economic advancement of poorly-educated immigrants, not to mention their children — who, on average, greatly surpass the income of their immigrant parents.

Even more than comparisons with other countries, comparisons with historical measures of America's own economic mobility can help us trace the state of economic mobility and opportunity. Americans seem to think that economic mobility is declining: Only 41% said in 2008 that they were better off than they were five years before — fewer than at any time in a half-century, according to Gregory Acs and Seth Zimmerman of the Urban Institute. But using the same Michigan data set described above, Acs and Zimmerman compared trends in mobility during the 1984-1994 period with trends during the 1994-2004 period. They found that 60% of those 25 to 44 years old moved up or down across income fifths in both periods. Nor did the stickiness of the bottom fifth increase: During both periods, a little over half of those studied moved out of the bottom fifth. Based on the best available data, then, there is no evidence that mobility has declined since the early 1980s.

But if things have not gotten worse, they have not gotten much better either, despite decades of enormous effort and expense by private and charitable enterprises and especially by government at every level.

The scale of government investment in the alleviation of poverty and the promotion of economic mobility is extraordinary. The best information about means-tested anti-poverty spending by states and the federal government is a study done periodically by the non-partisan Congressional Research Service. The most recent report provides detailed data for 1968 through 2004, and shows that during that period annual state and federal spending on anti-poverty programs increased from $89 billion to nearly $600 billion (in inflation-adjusted dollars). Simple calculations based on these numbers show that whether measured on a per capita basis, as a percent of federal spending, or even as a percent of gross domestic product, means-tested spending has grown since the War on Poverty began in the mid-1960s. And the CRS estimate, of course, includes neither the dramatic increase in spending already taking place under the stimulus bill enacted in February 2009, nor the additional increases called for under President Obama's proposed 2010 budget.

We can gain an even better understanding of the federal commitment to promoting economic mobility by focusing on the specific programs that are designed for this purpose. Adam Carasso, Gillian Reynolds, and Eugene Steuerle of the Urban Institute found that in 2006, the federal government spent $746 billion — or 5.7% of GDP — promoting economic mobility.

The bulk of this money, of course, comes from income taxes. And who pays the income taxes? According to the non-partisan Congressional Budget Office, in 2006 the top 5% of earners paid almost 60% of federal income taxes and nearly 75% of corporate taxes. By contrast, the bottom 40% of earners paid negative taxes; the Internal Revenue Service sent them payments equal to around 2% of their income.

The size and scope of federal spending on programs to boost economic mobility, paid for disproportionately by the rich, helps us to see that the current system — again in contrast to the common perception — is structurally designed to help the poor. But many years of evaluation studies show that most of these programs produce modest, if any, lasting impacts on participants. The effect of government assistance, in short, is not proportional to its scope and scale. Even so, the decades of data on which programs work and which do not allow us to sketch out a realistic public-policy agenda to aid economic mobility in America — provided we understand that the ability of government to change the underlying circumstances will always be limited, because economic mobility is constrained above all by personal choices and behaviors. Indeed, we need more public polices that are designed to provide incentives for individuals to make choices that will promote their own development and boost their own income.

THE OPPORTUNITY AGENDA

What, then, should policymakers do to help spur economic mobility in America? In our recently completed book, Creating an Opportunity Society, my Brookings colleague Isabel Sawhill and I argue that the latest data and analyses of this vexed question point to a familiar answer: that the best way to increase opportunity is to encourage strong families, more education, and full-time work.

To begin with, society — from parents and teachers to celebrities and political figures — should send a clear and consistent message of personal responsibility to children. They should herald the "success sequence": finish schooling, get a job, get married, have babies. Census data show that if all Americans finished high school, worked full time at whatever job they then qualified for with their education, and married at the same rate as Americans had married in 1970, the poverty rate would be cut by around 70% — without additional government spending. No welfare program, however amply funded, could ever hope for anything approaching such success.

Indeed, what distinguishes successful government programs to aid economic mobility is not how much money they spend, but how they approach the problem. Three strategies seem especially worthwhile.

The first is arguably the most effective approach the nation has yet devised for reducing poverty: bringing poor mothers into the mainstream economy and supplementing their earnings. The 1996 welfare-reform law has been highly successful in this regard; despite the relatively low wages of the women involved, employment has substantially increased their income. The reason is that welfare reform actually had two components: the widely known work requirements that bring mothers into the labor force, and the lesser-known work-support system that subsidizes all low-income workers, especially parents. This combination not only got between a million and a million and a half single mothers — most of whom would otherwise have been on welfare — to find jobs, but also drove down the poverty rate of female-headed families to its lowest level ever. The black child-poverty rate also reached its historical low, and even after the 2000 recession, child poverty was still about 20% lower than before the 1996 overhaul.

Our strategy now should be to expand both components of the 1996 reforms. Specifically, serious work requirements should be built into the food stamp program (the program's current work requirements are ineffective) and housing programs to get still more poor people into the work force. Once they arrive, they should find an expanded work-support system — especially additional funding for child care, and an expanded cash income supplement (through the Earned Income Tax Credit) for full-time workers who do not have custody of children. These reforms would bring more people — including young males — into the labor force and show them that they can improve their income even through low-wage work. The cost to taxpayers would be partially offset by increased tax revenue and reduced dependence on welfare benefits by those involved. And this approach would be consistent with the goal of requiring more responsible behavior by individuals and rewarding them if they do the right thing. It builds on the most successful policy innovation of the past several decades to further the cause of economic mobility, and uses government to encourage rather than undermine individual responsibility.

The second strategy is directed at the growth and development of poor children. It is widely accepted that high-quality pre-school programs can have lasting effects on child development — including children's school readiness, high-school graduation, delinquency and crime, earnings, and a range of other outcomes. The problem is that most of the evidence for long-term results comes from experimental, small-scale programs. Only weak evidence supports the claim that Head Start — a broad-scale program that serves 900,000 children — produces these types of long-term outcomes. Even so, states and localities are now using both federal and state dollars to develop large-scale quality pre-school programs.

We should embrace this growing movement by providing states with greater control of Head Start funding (now about $7 billion per year) if they agree to serve all pre-school children below around 150% of poverty, and agree to allow parents to select from a variety of programs. States should provide home-visiting programs to the small number of infants who are at great risk of poor development as indicated by family violence, child-abuse reports, parental drug addiction, or parents living in deep and persistent poverty. To receive federal funding, programs should include frequent testing of child outcomes, and improve these outcomes based on the results of testing. Programs must also test students when they enter kindergarten, with federal funds going only to programs that can demonstrate school readiness for most students from poor families.

The third strategy is to do everything possible to increase the share of children being reared by their married parents. Good studies have linked lone parenting (or the shock of transitions between family living arrangements) with poor education outcomes, delinquency and crime, mental-health problems, lower labor-force participation, and a host of other bad outcomes for children. Unfortunately, Americans have perfected every known way of producing lone-parent families; we are especially good at having babies outside marriage, boosting their share of all births from about 5% in 1960 to nearly 40% in 2006. We also still have the highest divorce rate among Western nations. As a result, nearly 30% of our children live in lone-parent families at any given moment, and nearly half spend time living apart from at least one of their parents before age 18. Among black children, about 70% are born outside marriage and up to 80% live in a lone-parent family sometime during childhood (many for virtually their entire childhood).

In 2007, the poverty rate for lone-parent families was over 28%, nearly six times the rate for married-couple families. Research shows that if we had the same share of children living in married-couple families as we had in 1970, poverty would decline by almost 30% without any additional government spending. The growth of female-headed families is like a giant poverty-generating machine. Even if government programs to reduce poverty become more effective, they would have an increasingly difficult time just offsetting the powerful upward push on child poverty caused by the continuing growth of lone parenting.

It is popular to argue that we could not roll back the causes underlying these trends even if we wanted to. But given the implications, we should not accept defeat on marriage and two-parent families. One way to push back is by reducing teen pregnancy and unwed pregnancy, because women who have babies outside marriage reduce their chances of ever forming a marital bond. Programs for adolescents that teach about reproduction, emphasize the value of abstinence, examine the values that surround teen sex, offer information about contraception, teach skills in avoiding unwanted sexual advances by partners, provide mentoring by adults, and encourage participation in community activities have been shown frequently and reliably to reduce teen pregnancy. (So far, there is not comparable evidence for abstinence-only programs.)

Unfortunately, there are almost no programs that have been shown to reduce pregnancy among unmarried twenty-somethings, a group that has grown rapidly because both males and females are now delaying marriage until later ages. Twenty-somethings have filled the marriage void with huge increases in rates of cohabitation and other non-marital relationships, which lead to equally huge increases in the frequency of sex outside marriage. Pregnancy for many of these couples is therefore all but inevitable, and perhaps the best policy goal with this group is to emphasize systematic use of birth control. For example, research shows that making birth control available through the Medicaid program significantly reduces non-marital births. Indeed, the Congressional Budget Office has recently calculated that increased spending on Medicaid to provide family planning to low-income females who are somewhat above the normal Medicaid income requirements actually saves money.

Of course, an even more direct means of ensuring that more children live with their married parents is to increase marriage rates — which have plummeted in the last three decades. Although college-educated women still marry at high rates (though later in life) and are much less likely to have babies outside of marriage, marriage is rapidly declining among the poor and minorities. The 1996 welfare-reform law allowed states to use welfare funds to mount pro-marriage initiatives, but few states did more than create token programs.

That's why George W. Bush, upon becoming president in 2001, mounted a vigorous campaign to support the fledgling marriage movement. His administration began awarding discretionary grants to a wide range of activities to strengthen couple relationships; funded community-wide pro-marriage initiatives that included media campaigns and divorce-reduction programs; and eventually began a $100 million competitive grant program to promote marriage while also funding a National Healthy Marriage Resource Center to provide technical assistance to the grantees. His administration also launched a series of large-scale studies on the effect that marriage-education programs have on poor unmarried couples who had (or were about to have) a baby, as well as on poor married couples with children. These studies, the first of their type to be conducted with poor couples, will begin reporting results in 2010. Based on these studies, we will know for the first time whether structured programs that teach such skills as managing finances, handling conflict, avoiding family violence, and showing love and affection can lead to increased marriage rates, reduced rates of separation and divorce, and improved well-being of poor children. If so, broader use of these programs is warranted. President Obama himself, in his book The Audacity of Hope, expressed his support for such programs.

BEYOND INEQUALITY

Taken together, these proposals make the point that although there is room for government to help advance the cause of economic mobility in America, it can do so mostly by encouraging personal responsibility. Poverty in America is a function of culture and behavior at least as much as of entrenched injustice, and economic mobility calls not for wealth-transfer programs but for efforts that support and uphold the cultural institutions that have always enabled prosperity: education, work, marriage, and responsible child-rearing.

Thus, the inequality debate is not nearly as relevant to the more important question of mobility as it sometimes seems to many advocates and politicians. Inequality is a cloudy lens through which to understand the problems of poverty and mobility, and it does not point toward solutions. Great wealth is not a social problem; great poverty is. And great wealth neither causes poverty nor can readily alleviate it. Only by properly targeting poverty, and by understanding its social, cultural, and moral dimensions, can well-intentioned policymakers hope to make a dent in American poverty — and thereby advance mobility and sustain the American Dream.