Campaign-Finance

Reform Revisited

The disputed role of money in politics is as old as politics itself, going back at least to Plato's warnings in his Republic about politicians' susceptibility to corruption. An old political adage suggests that campaign money is like water flowing downhill: It will find a way to flow around or through any obstacle you put in its way. In America, legislators have been faced with this problem since at least 1758, when George Washington's purchase of wine and cider for his fellow Virginians helped win him a seat in the Virginia House of Burgesses. The first law that specifically regulated the financing of campaigns was passed in 1867 (prohibiting government officials from soliciting funds from naval-yard workers), inaugurating a century and a half of ever-more-complicated campaign-finance reforms.

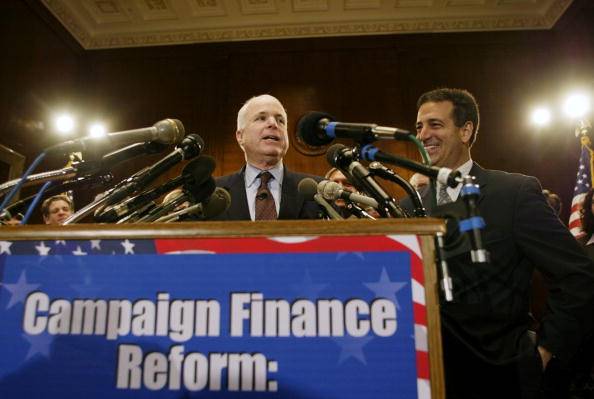

Now, over 15 years after the landmark Bipartisan Campaign Reform Act of 2002 (commonly known as "McCain-Feingold" or BCRA), most Americans still think there is too much money in politics. The notion that our campaign-finance system is "broken" is so commonplace as to be a cliché. It is routinely denounced as grotesque, plutocratic, cancerous, and barely disguised corruption — an excrescence on American democracy. At a time when popular agreement about important policy directions is notoriously elusive, this pervasive contempt for the campaign-finance system and demand for reform approaches a consensus.

Despite this widespread agreement, however, reforming campaign-finance regulations is anything but straightforward. The most difficult hurdle is the First Amendment, providing that Congress shall make no law "abridging the freedom of speech." Speech about candidates and public issues is core political speech, so virtually any restriction that Congress might enact in this area — whether relating to campaign contributions, spending, disclosure, media, commentary, or any other aspect of election activity — is under a constitutional cloud. Reform proposals vary widely, and few can agree on the role parties should play, the optimal degree of transparency, and how much influence money should continue to have. And our new digital media environment is creating new challenges.

Any new attempt at campaign-finance reform must address the causes of Americans' indictment of the current system, while staying within our First Amendment guardrails and respecting our most deeply held values. Only then can we hope to repair the public's declining trust in its government.

A COMPLICATED HISTORY

Our current regime began to take shape in 1971, when Congress replaced existing campaign-finance laws with the Federal Election Campaign Act (FECA), which required full reporting of campaign contributions and expenditures and put caps on spending and contributions. FECA did allow corporations and unions to use their funds to establish, operate, and solicit voluntary contributions for political action committees (PACs), which could then contribute to candidates.

In 1974, Congress established the Federal Election Commission (FEC), a nominally "independent" and bipartisan agency, to write regulations and monitor compliance. Congress authorized partial public funding for presidential primary candidates and presidential nominating conventions, enacted strict limits on both contributions and expenditures applicable to all elections, and permitted corporations and unions with federal contracts to establish and operate PACs.

In the 1976 case of Buckley v. Valeo, the Supreme Court upheld the law's contribution limits while rejecting its expenditure limits — a fateful distinction, as we shall see. In response, Congress repealed expenditure limits (except for candidates who accepted public funding), reconstituted the FEC, and significantly restricted PAC solicitations. The basic regulatory regime that has resulted, though launched by the FECA, is one that Congress never enacted and never would have created.

In the 1990s, fundraising efforts began to rely increasingly on contributions of "soft" (unregulated) money to parties to support particular candidates in ways that Buckley failed to prevent. So in 2002, Congress enacted yet another reform, the BCRA, hoping to plug this soft-money loophole and limit some other candidate-targeted expenditures. Specifically, the BCRA prohibited issue-advocacy ads targeted at a specific candidate within 30 days of a primary or 60 days of a general election, and barred any such ad paid for by a corporation. In 2003, the Court upheld these provisions. Inevitably, campaign donors responded by increasingly directing funds to non-party, non-candidate groups — PACs, 527 groups (which engage in issue advocacy and voter mobilization), 501(c) groups, and later on, Super PACs — all of which are largely unconstrained (depending on the group) by the BCRA's contribution limits and disclosure requirements.

Since then, the courts have decided four important cases upholding predictable efforts by partisans to directly challenge or circumvent the statutory restrictions on contributions and expenditures. In FEC v. Wisconsin Right to Life (2007), the Supreme Court ruled that the BCRA bans on electioneering communications during a 60-day blackout period could be applied only to ads that, on their face, clearly advocated the election or defeat of a specific candidate or party.

The Court's most controversial decision came in Citizens United v. FEC (2010), a ruling that the public opposes even more than the Court's gay marriage and abortion decisions. The case involved a nonprofit organization that had produced a documentary critical of then-candidate Hillary Clinton, which was distributed to viewers on DVD during the 2008 primary campaigns. Citizens United then wanted to broadcast the movie within 30 days of a primary election, which would violate BCRA's ban on using corporate (or union) funds for an electioneering communication or express advocacy within the statutory blackout period. Notably, the solicitor general stated in oral argument that the government could even ban a book funded by a corporate treasury during the blackout period!

In a then-familiar 5-4 split, the Court struck down the BCRA's rule barring the organization from paying for such communications — even if not coordinated with a campaign. Buckley, Justice Anthony Kennedy wrote, had upheld FECA's contribution limits specifically to counter quid pro quo corruption, and independent expenditures like the film were by definition not coordinated with a campaign and thus did not risk quid pro quo corruption or undermine public faith in our democracy.

Kennedy's opinion, however, also included an obiter dictum — a passing statement going beyond its actual holding (what is strictly needed to decide the case) — to the effect that Congress can legislate only against quid pro quo corruption, not against "undue influence" corruption. A strong partial dissent by Justice John Paul Stevens, concurred in by the three more liberal justices, argued that Congress's compelling interest in avoiding even the appearance of corruption justified barring corporate spending in campaigns; such spending, Stevens claimed, has "a distinctive corrupting potential."

In another decision, the Court struck down FECA and BCRA provisions that imposed aggregate limits on a single donor's campaign contributions to federal candidates ($46,200) and political parties ($70,800) during a given campaign cycle.

The fourth pivotal ruling, rendered in 2010 by the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals, extended Kennedy's dictum to allow Super PACs and other such groups to accept unlimited contributions and make unlimited "independent" electioneering expenditures. So complex has campaign-finance law become that even the late Justice Antonin Scalia claimed, "[it] is so intricate that I can't figure it out."

DEEP POCKETS

What exactly all that campaign money provides to a candidate is not straightforward either. Although every presidential election tends to break the previous spending record, 2016 was a striking exception: Both candidates raised significantly less than their counterparts did in 2012 — even though Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump were both new candidates. The Clinton campaign raised $623 million, much less than President Obama's $731 million. Donald Trump raised $335 million, which was also less than Mitt Romney's $474 million. As usual, the parties spent a fraction of what candidates and outside groups did. In 2016, candidates for the House and Senate spent $1.5 billion combined, more than twice the $688 million spent by the parties' national congressional committees.

Even more striking, campaign spending did not seem to affect outcomes much in either the primaries or general election. Trump won despite spending only a little more than half of what Clinton spent: $398 million versus $768 million. He was able to do this by capturing media attention at low cost — relying on Twitter, his own money, and extensive free news coverage — while Clinton depended more on paid TV advertising featuring almost relentless negative attacks. For these reasons, it is possible that the 2016 pattern was unique.

Spending and contributions do not fully measure a campaign's resources. Labor unions and volunteers, for example, also play a huge role. In the 2016 presidential election, labor unions were a significant force of support for Clinton. From January 2015 through August 2016, labor unions spent about $108 million on the election, a 38% jump from the $78 million they spent during the same period before the 2012 election, and nearly double their 2008 spending. Approximately 85% of their spending in 2016 supported Democrats. Clinton also exceeded Trump in volunteers. In October 2016, the Trump campaign had 207 field offices; Clinton had 489. In addition, a growing share of campaign spending is done by outside groups supposedly independent of the candidates and parties. In the 2016 presidential election cycle, these "independent" expenditures totaled $1.4 billion — 40% higher than in 2012.

Where do those funds come from? Citizens United's most notable aspect, especially in view of the jeremiads against it, is that the dire predictions about corporate spending have not been borne out in the four elections since that decision. Very few business corporations make political donations, and many of those that do are closely held firms. Corporate contributions to Super PACs comprised only $95 million out of the $6.5 billion spent on the 2016 election. Indeed, all outside spending (not just corporate) was only 22% of the total compared with 17% in 2000. (Again, the 2016 election may be an outlier in these respects.) Campaign spending, as just noted, has increased more slowly since Citizens United than before. Indeed, while a 19% increase in spending occurred between 2008 ($5.3 billion) and 2012 ($6.3 billion), campaign spending increased just 3.1% in 2016, to $6.5 billion. Super PACs are funded mostly by wealthy individuals, not corporations or unions, and they cannot pay for a candidate's campaign costs. And almost all post-Citizens United spending comes from individuals, not corporations.

Furthermore, in the 2016 election cycle, Super PACs and other fundraising efforts had no consistent effect on electoral outcomes. Super PACs support liberal campaigns as well as conservative ones; in 2016, the top Super PACs were evenly split between support for Clinton and Trump. A group funded by wealthy progressive donor George Soros spent hundreds of millions of dollars to get out the Hispanic vote, which would presumably aid Democratic candidates. Donations from individuals greatly exceeded donations from PACs: In 2016, House Democrats received around 40% of their donations from PACs and 57% from individual donors; House Republicans received approximately 45% from PACs and 48% from individual donors. In the Senate, the disparity was even more extreme. Senate Democrats received only 24% from PACs and nearly 72% from individuals; for Senate Republicans, the shares were approximately 27% and 65%.

As I discuss below, money is far from decisive in elections. While financial support is indispensable for viability as a candidate, political scientists find that other resources are usually more decisive — and help attract campaign contributions in the first place. These include organizational skills; past contacts or ties; the size, intensity, and thus influence of interest groups; tactical expertise; valuable information; media access and free ("earned") TV time; personal charisma or eloquence; name recognition; dynastic power; persuasive arguments; propitious timing; a compelling life story; and, especially, incumbency. In 2017, the Republican candidate in Georgia's sixth district, rich in many of these resources (though not an incumbent), defeated a Democratic opponent who spent more than four times what she did, in the most expensive House race in history.

Many people express horror at the amount of money spent on elections, and the $6.5 billion spent in 2016 does seem like a lot. But comparing campaign spending to what we spend on other things provides another perspective. Holiday shopping, for example, was forecast at almost $617 billion in 2014; indeed, the National Retail Federation expected more than $31 billion to be spent on holiday gift cards alone. The average holiday shopper spent $804, whereas an infinitesimal share of Americans (0.23%) spent more than $200 in that year's election cycle. In 2016, the cosmetics industry's revenues were estimated to exceed $62 billion. In 2015, Americans spent $4.7 billion on the five most common cosmetic surgeries alone, and another $3.3 billion on the five top non-surgical cosmetic procedures. Consumers in the U.S. and Canada also spent more than $10 billion on movie tickets in 2014, almost triple what was spent on the U.S. congressional elections that year. Indeed, political scientists have long puzzled over why there is so little money spent on campaigns, given the high stakes for economic interests. (Lobbying expenditures, which are many times greater, will be discussed below.)

The donor population has grown significantly in recent years — 416,696 more individuals in 2016 than in 2012 — but it remains small. In the 2016 election, a tiny elite portion (0.52%) of the U.S. population gave more than $200. Together they delivered 69.2% of the total received in the 2016 cycle. While elite donors have historically tended to favor Republicans, recent elections have been more favorable to Democrats. In 2016, donors who gave between $2,700 and $9,999 contributed 43% to Democrats and 32% to Republicans. Those who donated more than $10,000 gave 29% to Democrats and 25% to Republicans. Those who contributed more than $100,000 gave 20% to Democrats and 18% to Republicans.

Preliminary numbers for the 2018 elections (just concluded as this article went to press) suggest that the cycle set new records for midterm-election contributions and expenditures. Shortly before the elections, the Center for Responsive Politics estimated total spending of $5.2 billion, a 35% increase over 2014 in nominal dollars. (Presumably, even these 2018 numbers will increase because of continuing contestation of outcomes due to recounts and voting irregularities.) Outside spending, at $1.31 billion, increased 61% over 2014. Particularly costly were the Senate races in Texas — Beto O'Rourke raised more money than any Senate candidate in history (almost half of it, remarkably, from small donors), and his race with Ted Cruz was the most expensive Senate race ever — and in Florida, where Rick Scott was approaching O'Rourke's record in the runup to election day. Spending by Super PACs and individual donors also set new records.

THE APPEARANCE OF CORRUPTION

The problem with money in politics is the scent of corruption that it leaves on the democratic process. The fact that most campaign funds come from a very small number of individuals causes skepticism among many Americans, who worry that their representatives are more interested in serving the interests of their donors than those of their constituents.

Campaign-finance critics routinely insist that money buys elections and votes in Congress and that it goes disproportionately to conservative candidates. Christopher Achen and Larry Bartels recently argued that donors' preferences influence policy outcomes more than do voters' preferences, which respond largely to social identities and partisan loyalties. Yet other political scientists consistently find that the effect of campaign spending at the margin is either small or shows no consistent pattern. The canonical study, conducted by Stephen Ansolabehere and colleagues, was published in 2003 and confirmed in a 2012 literature review.

The evidence that campaign contributions lead to a substantial influence on votes is rather thin. Legislators' votes depend almost entirely on their own beliefs and the preferences of their voters and their party. Contributions explain a miniscule fraction of the variation in voting behavior in Congress. Members of Congress care foremost about winning re-election. They must attend to the constituency that elects them (voters in a district or state) and the constituency that nominates them (the party). This helps to explain why there is so little money in elections compared with the enormous amounts invested by organized interests to influence government policy through lobbying and other means.

Money has little leverage because it is only a small part of the political calculation made by legislators focused on re-election. And interest-group contributors — the "investors" in the political arena — have little leverage because politicians can raise sufficient funds from individual contributors. It is true that when economic interest groups give, they usually appear to act as rational investors. This "investor" money from organized groups, however, accounts for only a small fraction of overall campaign spending. Since interest groups can get only a little from their contributions, they give only a little. As a result, interest-group contributions account for a small amount of the variation in voting behavior at most. In fact, after controlling for legislator ideology, these contributions have no detectable effects on the behavior of legislators.

So, what does influence legislator behavior? A detailed study of the repeal of the estate tax in 2001 finds that campaign contributions played a much smaller role than money spent for core protected speech, such as research and publishing, political organizing, disseminating opinion, and lobbying. The study's authors found that Washington insiders' "most frequently repeated view was that campaign contributions are overrated when it comes to getting legislation passed. [They] consider lobbying and interest groups far more important." Political scientist Nolan McCarty has suggested that any effort to further restrict campaign contributions or spending would simply divert the money to increased lobbying, where equalization and control are much more problematic for both legal and practical reasons.

Indeed, far more is spent on lobbying than on campaigns. In 2016 alone, $3.15 billion went into lobbying, and that number increased to $3.37 billion in 2017, as the number of registered lobbyists grew. Notably, the seven top-spending individual lobbyists in the 2016 election cycle gave all or almost all of their contributions to Democrats. Lobbying, however, cannot be limited constitutionally, while contributions can. So efforts to restrict money's influence on politics are limited to campaign finance.

Clearly, Congress has a compelling interest in combating corruption and the appearance of corruption. The Supreme Court affirms that, as do most legislators and voters. But agreement ends there. Debates and litigation over campaign-finance policy often center on which kinds of conduct or conditions constitute impermissible political corruption.

The Citizens United majority held — correctly, in my view, based on that case's specific facts — that the film qualified as an independent expenditure under current rules. But the majority went further than it had to with its dictum stating that Congress could bar only quid pro quo corruption, not undue influence. It also ignored the reality of widespread campaign coordination of supposedly independent expenditures.

Political scientists, election-law experts, and journalists have found little evidence of explicit quid pro quo; making a donation, requesting action, and expressing gratitude does not amount to corruption. A unanimous 2016 decision by the Court made this even clearer (although the case was a federal criminal prosecution, not an enforcement action under the campaign-finance laws). And it is hard to see how "undue influence" can be distinguished factually and morally from the normal and accepted practical politics of influence in a representative democracy, not to mention other sources of influence not necessarily connected to campaign contributions. (This analysis is consistent with the Justice Department's dropping its corruption case against Senator Robert Menendez in 2018.)

As for "independent" expenditures, the Supreme Court held in Buckley that Congress cannot restrict them, and it has repeatedly reaffirmed that principle. The Court's rationale was that expenditure limits restrict the freedom of speech and association far less than contribution limits do. But the logic of this distinction is dubious. First, it is hard to see how giving money to a PAC that uses it to urge voters to "elect Smith" communicates any more than does giving money directly to Smith, who goes out and says the same thing. Second, such a distinction based on fear of corruption should not apply at all to spending by parties whose very purpose is to promote their candidates, yet the Court has applied the distinction to party spending as well.

The fact that so much, legally, turns on the independence of these expenditures raises an obvious question: In reality, how independent are "independent" expenditures? In practice, campaigns and Super PACs use various well-known ploys and loopholes to circumvent the congressionally emasculated FEC's restrictions on coordination of spending and message. The coordination ban is meaningless in a political world where parties, interest groups, candidates, media, and many others constantly interact in and manipulate an extremely complex field of subtle influences, intimate relationships among the players, anticipated reactions, and winks and nods. Issue ads are an important example of this enforcement dilemma. These ads are core political discourse, not linked explicitly to a candidate, yet they effectively aid those candidates who share the substantive position that the ads advocate — and they are intended to do so, as everyone knows. Also straining any commonsense notion of independence are certain practices of Super PACs, especially those set up and funded by former aides, family, or close friends of a favored candidate for the express purpose of electing that candidate.

Another factor that raises eyebrows is the relationship between incumbency and campaign finance. Vastly more campaign contributions go to incumbents in Congress or the White House than to challengers: Donors want to return incumbents to powerful positions where they can (continue to) benefit the donors and their causes. And this incumbency advantage compounds others: seniority in Congress, name recognition, franking privileges, knowledge of the district, experienced staff, favorable districting maps, voter partisanship, and the fact that they write the campaign-finance rules and influence how the FEC will enforce them. This helps explain why representatives win re-election at such high rates. Citizens United, for its part, actually seems to have reduced the incumbency advantage somewhat. (And parties do sometimes support insurgent candidates.)

The rich, by definition, have much more money than their fellow citizens do and can use it to gain greater access or influence, multiplying their existing advantages. But the Court has emphatically and unanimously rejected the notion that Congress can justify spending or contribution limits to achieve equal access or influence. And many of the non-monetary advantages in politics discussed earlier are distributed even more unequally than wealth is. Another glaring source of inequality in campaign finance is the privileged constitutional status of media. It is hard to see why some speakers should be limited when the New York Times, Wall Street Journal, Fox News, MSNBC, and countless other publications, digital platforms, and broadcasters are free to spend as much money as they like to speak through their influential megaphones.

Finally, the laws that regulate campaign contributions and spending tend to diminish the role and effectiveness of parties. Today, the parties cannot control the flow of money into campaigns, which gives them much less leverage over the candidates, their messages, and their tactics in elections. As I discuss below, weak parties worsen the problem of money in politics, and any reforms to the current system should minimize any further party-weakening effects.

In fact, this sort of perverse effect is pervasive in campaign-finance law. The rules intended to bolster public confidence in the electoral and representative processes seem to have done just the opposite. The more Congress has enacted new reforms to fix the loopholes left in the previous ones, the more election consultants earn — and the more cynical the public becomes about the system.

REFORMING CAMPAIGN-FINANCE REFORM

Law professor David Strauss notes a "curious feature" of many reform proposals: "[T]he cure often precedes the diagnosis; and the diagnosis, when provided, is often a little vague." He is right; neither the consensus nor the jeremiads against the system tell us much about just why or how it should be reformed. To some critics of the system, particularly on the left, the dysfunction's causes are clear: growing Republican extremism and Citizens United. Most disputants differ on whether there is too much money in politics, whether more of it should flow through the parties, whether transparency is always a good thing, and whether contributions corrupt politics, among other questions. Many politicians join the reform chorus, claiming that "dialing for dollars" is demeaning, time-consuming, and a perverse diversion from their more important legislative work. But it is questionable whether enough incumbents would actually vote to change a system that they have mastered, that helped put them in office, and that keeps their future challengers at a serious disadvantage.

In considering possible reforms, we must remember, as Morris Fiorina and his co-authors put it, "how little we genuinely know about the operation of complex political processes and institutions, and, consequently, how likely it is that proposed reforms will prove ineffectual or, worse, counterproductive." The history of campaign-finance reforms certainly confirms this warning.

Many reformers therefore suggest changes on the margins of the current campaign-finance system, such as mandating free TV time, encouraging small donors and more disclosure, and implementing public campaign funding. Purchasing TV time has grown ever more expensive, and TV exposure can be an important political advantage (or disadvantage, depending on the candidate's performance). Reformers have proposed that Congress or the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) require networks to provide free or reduced-fee time to candidates for public office (though not their parties, as is done in many peer democracies). These proposals have never attracted much support, and broadcasters oppose them for obvious reasons. Incumbents who enjoy media access by reason of their prominence and official positions have no incentive to provide it free to their challengers. The traditional argument for free TV time — that the broadcast spectrum is a public resource granted by the FCC and that its use by networks is not a private-property right but a privilege to be allocated for public purposes — has become more tenuous with the spread of other forms of media. In addition, a free-time system would necessitate difficult judgments distinguishing between bona fide candidates and mere publicity hounds.

Federal law does impose an "equal time" rule requiring broadcasters to provide equal opportunities to all political candidates, but First Amendment concerns have qualified the rule with several important exceptions for documentaries, bona fide news interviews, scheduled newscasts, or on-the-spot news events, which in practice mitigate the rule's equalizing potential. Broadcasters must offer time to candidates at the rate charged to the "most favored advertiser," but that rate is still very high.

Reformers often seek to increase the number and influence of small donors as well, believing that the unequal influence that is blessed and arguably magnified by the existing system poses a serious threat to our democracy. But there are reasons to be wary. Small donors tend to cluster at the ideological extremes, and they already participate disproportionately in politics. They tend to be the same people who contact politicians, organize at the grassroots, and turn out for caucuses, primaries, and general elections. As for transparency, small donors need not disclose their contributions to federal candidates until the amounts exceed $200.

Greater disclosure of campaign contributions and expenditures is also frequently proposed by reformers. The virtues of transparency are relatively non-controversial because the benefits are obvious, the costs seemingly trivial (though harassment and retaliation are possible), and enforcement fairly straightforward with each party monitoring the other's (non-)compliance. And the Supreme Court, starting with Buckley and even in Citizens United, has upheld disclosure mandates, which increase public information without suppressing speech. Ever since Citizens United allowed unlimited independent expenditures by outside groups (absent coordination), coalitions in Congress have tried but failed to enact legislation, known as the DISCLOSE Act, to mandate disclosure of dark money and other financial information.

Another common reform idea proposes mandatory or, more often, optional public funding of campaigns. In practice, this has meant public funding of candidates, not of parties — although public funding could be used to buttress parties rather than candidates, as in some other countries. For federal elections, FECA currently makes public funding available only to presidential campaigns that agree to limit their spending, but this system has atrophied in recent elections as candidates opt for unlimited spending.

My Yale colleagues Bruce Ackerman and Ian Ayres have taken the public-funding idea an ingenious step further, advancing a two-part proposal: public funding and donor anonymity. The public-funding part draws on the idea of vouchers, which are popular in education, housing, and other settings. The government would issue registered voters a certain number of "Patriot dollars" on a digital card that they could dispense to candidates, parties, or PACs of their choice. Private contributions of other dollars would still be allowed, and contribution limits would be raised. But to keep private contributions from swamping the Patriot dollars, a "stabilization algorithm" would kick in when the private contributions amounted to half the Patriot dollars being contributed; the algorithm would increase the number of Patriot dollars in the next election cycle. PACs would have to give Patriot dollars they receive to candidates or parties; they could not use them for independent expenditures or other PAC activities. A similar idea is being implemented in Seattle, where a 2015 ballot initiative authorized the city to distribute $100 in vouchers to all registered voters, which candidates could use if they abided by certain contribution and spending limits.

David Strauss sees some advantages in such vouchers but fears that they might further entrench incumbents. Indeed, as discussed earlier, incumbent entrenchment is a serious constraint on the efficacy of most reforms, including public funding, since incumbents write the rules. For example, they could keep the funding for challengers low enough, and its availability regulated enough, to maintain their own fundraising and other advantages.

If Congress enacted a system that infused public funds into presidential or congressional campaigns based on some government match of small contributions, the Court would almost surely uphold it. But if it included a trigger for public funds based on the opposition's spending, the Court (barring a change in membership) would likely strike it down as an effort to "level the playing field" — a goal that the Court has explicitly rejected even if it increases protected political speech, reduces the risk or perception of corruption, and lowers candidates' fundraising burdens.

More aggressive reform proposals often take aim at the "independent" expenditures protected by Citizens United. As noted earlier, that decision is extraordinarily unpopular with the general public. But its actual holding was correct: The First Amendment and the BCRA do and should protect a group's right to spend its own funds on criticizing a candidate if that spending is truly independent of a campaign and not in reality a campaign contribution. What is unconvincing is the majority's dictum that independent expenditures never create an appearance of undue influence, and that even if they do, Congress cannot regulate them at all.

My earlier analysis shows how hard it would be to frame and enforce such a law defining and punishing undue influence. Money is only one source of political influence and not necessarily the most decisive. The incumbents who would enact such a law have powerful self-protection tools. Even if the Court allowed Congress to legislate against undue-influence corruption, the Court's strict-scrutiny standard would cast a long shadow over the difficult line-drawing needed to design such a law.

Independent expenditures, which are constitutionally protected, pose a similar enforcement problem. The key criterion of independence, of course, is coordination with a campaign. As discussed earlier, the operational distance between campaigns and their Super PAC and other group supporters is often illusory, consisting of obfuscatory tactics that any crafty campaign-finance lawyer can design. Nor does the FEC, assiduously neutered by Congress, have the ability to patrol this line.

Two quite different reform proposals would address this problem by changing the treatment of independent expenditures. One would tighten the definition of coordination to render such evasions illegal, while also banning practices that have that evasive effect, regardless of intent. Even without altering its precedents, the Court might well uphold such a law, thereby enforcing existing rules; only those who object to the existing contribution and expenditure limits would complain. In reality, however, it would surely be difficult (especially with a weak FEC) to enforce such a scheme while not crossing the uncertain lines that the Court has drawn to protect independent expenditures.

A better, more realistic reform would turn the independence-enforcement approach on its head. Instead of trying to police the boundary between the parties and the outside groups that purport to spend "independently" of the party candidates they support, this reform would make a virtue of necessity by ratifying and legitimating the coordination between outside groups and the parties. This would give parties ultimate control over the spending and end the hypocrisy, obfuscation, and Alice-in-Wonderland distortion of the supposed separation. It seems likely that many of these groups would welcome the chance to coordinate openly with the parties so as to increase their funds' effectiveness. Encouraging this coordination would also be one important way to strengthen the parties.

Many "realists" propose to encourage such coordination. They would redesign campaign-finance regulation to give parties more, not less, control over their donors and their candidates' messages, campaigns, and behavior once in office. As Stanford professor Nathaniel Persily explains, this strategy "takes as a given the huge demand for campaign funds and the inevitable influence of large independent expenditures in the post-Citizens United world. However, instead of trying to clamp down on the influence of all participants in the campaign finance system, the pro-party approach seeks to rectify the imbalance between insiders and outsiders by amplifying the voice of the parties so they can compete with outside groups."

The pro-party reformers readily acknowledge how hard this would be to achieve; after all, the trends have moved in the opposite direction for more than a century. Ever since the Progressive era's anti-party reforms, powerful forces have conspired to keep them weak. Candidate selection, necessarily at the heart of parties' power, has devolved to primaries, the outcomes of which are shaped by a relatively small, unrepresentative subset of each party's voters who tend to be the most narrowly focused, ideologically extreme, and most strongly resistant to bargaining and compromise even within the party itself.

Party-weakening and party-capture continue today. In 2016, a quarter of Democratic convention delegates were union members and more than a third of Republican delegates were from majority-evangelical districts. Over half the states now have some form of election law in which independents and even members of the opposing party can, and often do, vote in a party's primary, further diluting its autonomy, coherence, and solidarity. Those who advocate these more open primaries, including California's recently enacted "Top Two" system, usually argue that it will make the parties more moderate, but the evidence does not yet confirm this prediction, and it would not apply to presidential races.

Pro-party "realists" claim that the BCRA ban on soft-money contributions to parties simply starves the parties of needed funds while enabling wealthy donors to exert more influence through unaccountable non-party groups. Professor Nolan McCarty, a prominent realist, summarizes the pro-party view: "Strong political parties have autonomy from and bargaining advantages over special interest groups. Weak parties are those whose elected officials are free agents who can build electoral coalitions around narrow and extreme interests." Ample evidence supports this view. Extreme polarization in Congress (and the states) does exist and is bad for our democracy. The realists blame it partly on party-weakening (especially campaign-finance) reforms that tried to use Canute-like fiats to abolish political realities and to prevent politicians from doing what they must to survive in an increasingly complex system — with predictably bad results. Instead, these reformers want to use the powerful political hydraulics of our system to restore strong parties and moderating incentives that the recent reforms have undermined. Respecting these realities, they think, can make unintended consequences less likely.

The problem, they fear, is that our personality-obsessed popular culture may simply have changed too much to nourish trust in parties unless they are led by charismatic leaders. The speed and ease with which Donald Trump took over the Grand Old Party dramatically exemplifies this problem.

WHAT CAN'T BE REGULATED

Campaign-finance regulation is supposed to reinforce public confidence in the electoral and representative processes, but it seems to have done just the opposite. Indeed, the more Congress has enacted new reforms to fix the loopholes left in the previous ones, the more cynical the public has become about the system.

Yet reformers continue to debate how politics should be organized and funded, and the Court will, for better or worse, continue to constrain their efforts — particularly if Justice Brett Kavanaugh joins his conservative colleagues on this issue. Its campaign-finance jurisprudence is laced with constitutional interpretations that are now deeply embedded. Two central pillars of this jurisprudence — a narrow conception of the kind of corruption that might justify restrictions and a broad conception of independent expenditures that are protected — mean in effect that reformers can hope to work only at the margins of campaign-finance activity. Congress, an assembly of incumbents, is not about to rock the boat. And as campaign activity moves inexorably to the internet, the most important rules will increasingly be prescribed there — and not by Congress or the Court.

Indeed, the internet and especially social media have transformed the way campaigns are run — and to an extent how influence is distributed. Much core campaign work — including communication with potential voters and donors about candidates, issues, fundraising, and mobilization — has moved online. But with the vast majority of Americans now having a social-network profile of some kind and receiving much of their news through social-media portals, this data could be (and likely has been) misused to distort elections. (Indeed, anti-Trump employees at Facebook reportedly explored using this data to weaken his candidacy, only to be rebuffed by their superiors.)

In the aptly titled essay "The Campaign Revolution Will Not Be Televised," Persily argues that our thinking about campaign finance and its regulation is rooted in a technological relic: the 30-second TV ad. Lost in the furor over Citizens United, he says, is that the film at issue was online and accessible only to those who sought it out, unlike traditional TV spots. Online voter-targeting platforms such as Google, Facebook, and Amazon are the future vehicles for campaign money and will raise even more constitutional and practical problems than the regulation of traditional media.

In addition, Congress and the FEC cannot control online campaign ads as either a practical or legal matter. No federal agency can control a foreign website, nor can it easily distinguish domestic websites from traditional media whose election coverage and endorsements (and the money spent on this) are constitutionally impervious to regulation. Indeed, as Persily points out, any rule that depends on establishing the identity of the online speaker would be hard to implement: "[T]he internet is potentially even more fertile ground for anonymous, unaccountable spending....[A] website video could come from any source anywhere in the world....The internet...provides the perfect breeding ground for the most polarizing, least accountable, and most finely targeted forms of political communication."

Persily concludes that effective regulation — addressing non-discriminatory access, tone, disclosure, misrepresentation, and fairness — will have to come from the online portals themselves as they refine their existing rules for commercial and other users in light of the many new challenges posed by online campaigning, trolls and hackers, and the limited constitutional power of the government to prescribe such rules directly. In this new world, he speculates, "private regulation...may be better positioned to preserve democratic values than the government ever could."

The 2016 election was such an outlier in so many ways at least in part because we are living in a new political and technological paradigm where the old rules that governed influence in politics no longer apply. Campaign-finance reformers must wrestle with these new conditions (and some not yet foreseen) as they look toward future elections.