Bad-faith Interpretation

America is a nation of laws. Our bedrock law is the written United States Constitution. For that document to mean anything at all, we must share a more fundamental commitment to following the laws. And for that commitment to be meaningful, we must believe in the possibility of arriving at a shared understanding of those laws.

If, instead, our laws are routinely emptied out and filled up with whatever meaning the combatants in our political debates can get away with, our constitutional forms are themselves vitiated. Those in power may go through the motions of constitutional government, claiming to be doing nothing out of the ordinary, but their actions will consist solely of manipulating means to produce desired ends. No doubt they will tell themselves the generally degraded state of the system justifies their own selective obedience — after all, statesmen with the courage of their convictions would never agree to tie their own hands while their political adversaries claw and gouge. Since they believe their opponents are acting in bad faith, they feel compelled to set aside their own allegiance to the law.

The assumption of bad faith defines and disfigures our politics. The second Trump administration has been unusually aggressive about justifying its actions by characterizing them as reversals of previous bad-faith actions. If its officials sometimes contradict the letter of the law, surely they are legally justified in stopping "fraud" and "abuse" without delay. Elon Musk, Donald Trump's government-reform consigliere, said of the U.S. Agency for International Development that it was not an apple with a worm that needed extracting, but itself "a ball of worms." President Trump echoed the sentiment, saying that "radical left lunatics" running the agency had given it over to fraud, justifying immediate closure.

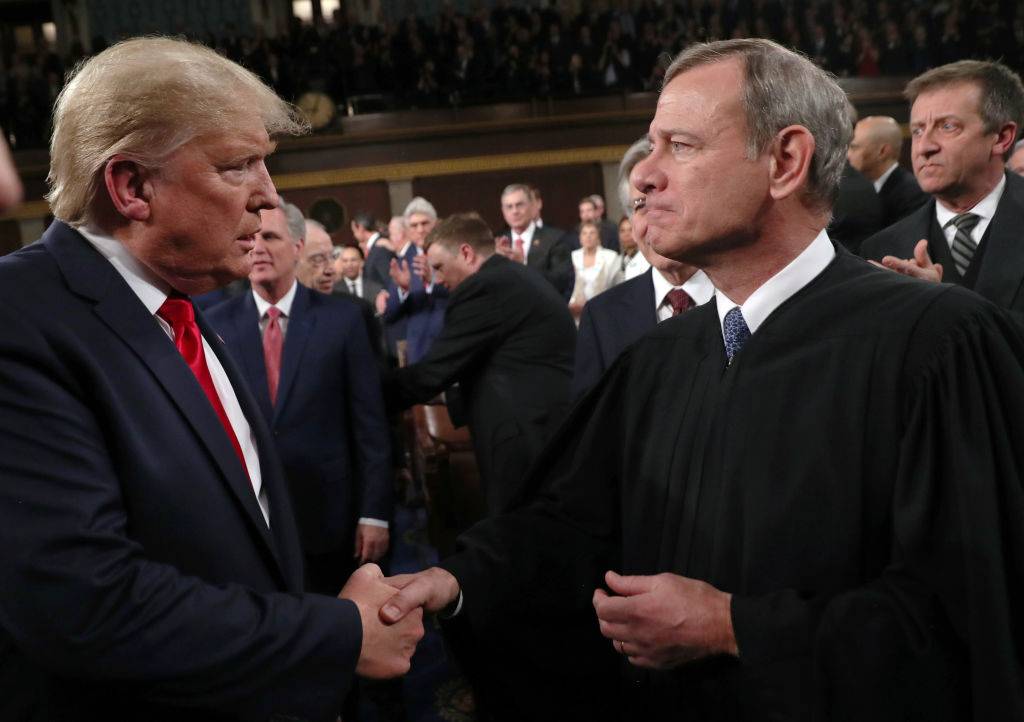

Among the core constitutional duties of the president of the United States is that "he shall take Care that the Laws be faithfully executed." Federal judges and justices of the Supreme Court also swear an oath to "faithfully and impartially discharge and perform all the duties incumbent upon [them]." But how can we proceed if we assume that many of the laws themselves are corrupted and corrupting? Or that the lawmaking process is fundamentally broken or unreliable? Is there any way out of the morass of mutual suspicion?

It is with these urgent questions in mind that we ought to examine recent doctrinal developments in administrative law and statutory interpretation, and especially the changing valence of textualism. Today's conservative Supreme Court majority observes the capriciousness engendered by bad-faith interpretation — including opportunistic and phony textualism in service of an overweening executive — and seeks to show the way back to good-faith debates situated in Congress. By policing executive-branch excesses, the justices hope to create space for meaningful political debate and compromise.

Their critics, unsurprisingly, allege that the justices are themselves operating in bad faith, with no real expectation that Congress will reemerge as a central policymaker. Pretending to promote the moribund legislature, they argue, is just misdirection; the real goal is to empower judges to decide policies for themselves. Justice Elena Kagan has been especially cutting in her denunciations of the majority's approach, arguing that conservatives have betrayed their commitment to textualism so that they can weaken Democratic administrations.

The judiciary's reactions to the second Trump administration will go a long way in showing which side is right. But more fundamental questions are beyond the power of the courts to resolve. Can our deeply mistrustful parties ever prioritize respect for the law? If they cannot, is the law itself important enough to fight over? If not, does our de facto constitution bear any resemblance to our de jure Constitution?

TEXTUALISM AS CORRECTIVE AND LAUNCHING PAD

Today's struggles over interpretation bear some resemblance to those of a half-century ago, though some of the positions involved have scrambled.

In the 1970s and 1980s, conservatives turned textualism into a sophisticated critique of bad-faith judging. They denounced judges who extracted from statutes whatever meanings they preferred by using a varied assortment of interpretive tools, including reference to legislative histories, speculation about legislative intent, and appeals to laws' broader purposes.

The antidote textualists offered was an insistence on putting the text first — treating the words that were enacted into law as superior evidence of what a law is supposed to do. Other materials would not necessarily be rejected entirely, but their use would be regarded with suspicion, especially because of the way subgroups of legislators with no constitutional standing on their own might strategically manipulate the record. Obedience to the text itself, Justice Antonin Scalia explained in 1989, would ensure that we were a nation of laws rather than of personal rule. Judges would be confined to their proper constitutional role as interpreters of what the law is, rather than creative contributors to struggles about what the law ought to be.

Scalia's critique was quite successful at discrediting the "purposivist" approach to legal interpretation as an invitation to judicial policymaking. The resulting regime was one of respect for the clear text of the law, coupled with an acknowledgment that legal texts could not be expected to answer every question. Consistent with the textualist impulse to cabin judicial discretion, a broad agreement emerged after the 1984 case of Chevron v. Natural Resources Defense Council that judges should give deference to executive-branch interpreters in construing ambiguous statutes, as long as they did so in a reasonable way. Given that this doctrine emerged during a dozen years of Republican presidencies, this suited conservatives just fine.

Textualism's triumph seemed to augur well for congressional supremacy. Because judges would always privilege statutory text, legislators could clearly set the outer limits of a law's scope. Judges, meanwhile, would get out of the policymaking business, often offering dicta to the effect that what the statute commands may or may not be good policy, but it is what Congress has passed into law, and it is for lawmakers to address any deficiencies as they see fit.

Yet there were signs, even early on, that the new reliance on text could be mobilized in favor of ambitious new government projects in ways Congress never anticipated. The trailblazing move in this regard was the 1996 decision of the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to henceforth regulate nicotine as a drug, despite the agency's having historically disavowed any jurisdiction over tobacco products. The agency justified this action with reference to the Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act's (FDCA) broad definitions of "drug" and "drug delivery devices." On a plain reading of the text, which refers to "articles (other than food) intended to affect the structure or any function of the body," nicotine and cigarettes seem to fall squarely within the act's scope. When tobacco companies challenged the regulations as impermissible, simple respect for the statutory text seemed as though it should decide the case for the agency.

Writing for a 5-4 Supreme Court majority, however, Justice Sandra Day O'Connor rejected that conclusion. She said that all the evidence weighed against the FDA's having jurisdiction, unless one succumbed to the temptation of "examining a particular statutory provision in isolation." Congress had never given any indication that the agency was supposed to regulate tobacco, and the tools available to it under the FDCA were poorly suited to the job. What's more, Congress had actively given jurisdiction over tobacco to other government actors. Respect for all the text, therefore, led to the conclusion that tobacco was excluded. In another case a year later, Justice Scalia would memorably characterize the majority's operative principle: "Congress, we have held, does not alter the fundamental details of a regulatory scheme in vague terms or ancillary provisions — it does not, one might say, hide elephants in mouseholes." Justice Stephen Breyer's dissent in the tobacco case insisted that the broad definition ought to be taken on its own terms, and that all the majority's other considerations "do not defeat the jurisdiction-supporting thrust of the FDCA's language and purpose."

Breyer's wielding of the law's "jurisdiction-supporting thrust" anticipated a flurry of 21st-century attempts to use open-ended statutory provisions as launching pads for new initiatives — what I called, in a 2013 article, efforts to "teach an old law new tricks." In 2007, regulation-seeking litigants convinced the Supreme Court to declare that the 40-year-old Clean Air Act, designed to abate local air-quality problems, had to be applied to the problem of rising global concentrations of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. Barack Obama's administration gladly complied, making an "endangerment finding" in 2009 and launching countless regulatory programs as follow-ons. After initially insisting that the nation's immigration system could only be remade by Congress, Obama found ways to repurpose the powers granted to him by existing laws to create a whole new class of quasi-legal migrants. Obama appointees on the Federal Communications Commission subsequently repurposed antique communications laws to create an ambitious regulatory program for the internet — what became known as "net neutrality."

In Joe Biden's responses to the Covid-19 pandemic, opportunistic textualism truly blossomed into a complete mode of governance, only to find significant resistance from the Trump-renovated Supreme Court. The Centers for Disease Control instituted an eviction moratorium, which the Court vacated in Alabama Association of Realtors v. Department of Health and Human Services. At Biden's prompting, the normally low-profile Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) promulgated a sweeping vaccination mandate for all employers with at least a hundred workers, which was blocked in National Federation of Independent Business v. Department of Labor. Biden also continued building Obama's edifice of climate law on the Clean Air Act, but was ultimately rebuked in West Virginia v. Environmental Protection Agency.

In dissents defending the Biden administration's actions, Elena Kagan turned the old textualist pieties against her colleagues. In a 2015 talk, she had famously declared: "We're all textualists now." But during Biden's tenure, she charged that the conservative majority on the Court "is textualist only when being so suits it." In her view, principles like the major-questions doctrine magically appear, serving as "get-out-of-text-free cards" that allow her colleagues to do as they please. Likewise, in reversing the longstanding doctrine of Chevron deference (in Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo), the majority had allowed a "rule of judicial humility" to give way to "a rule of judicial hubris." Kagan's charge is that although the conservative judges purport to be vindicating Congress's interests, they are simply consolidating more power to decide policy for themselves.

SHOULD WE BE HEROES?

The case that puts the new conflict over textualism in starkest relief is Biden v. Nebraska, a 2023 case in which the Supreme Court struck down one of the Biden administration's signature initiatives: an immense student-loan-relief plan estimated to cost the federal government some $430 billion. Examining the details of the case and the justices' dueling opinions allows us to see how competing claims of bad faith play out in practice.

The statutory hook on which the administration hung its initiative was the Higher Education Relief Opportunities for Students (HEROES) Act of 2003. That law gave the secretary of education discretionary authority to "waive or modify any statutory or regulatory provision applicable to the student financial assistance programs...as the Secretary deems necessary in connection with a war or other military operation or national emergency." The combination of an existing national-emergency declaration addressing the Covid-19 pandemic (put in place by Trump in March 2020) and this broad statutory language gave the Biden administration all the room it felt it needed to undertake an enormous loan-relief program, fulfilling one of the president's campaign promises.

A legal memorandum issued by Trump's Department of Education before the end of his first term had disclaimed any authority to mount a full forgiveness program under the HEROES Act, but the Biden administration swept away this inconvenient interpretation in 2022 and replaced it with a memorandum coming to the opposite conclusion. Given the extent to which the real goal was patronage for a certain class of Democratic supporters rather than relief of the neediest debtors, the administration concluded that passing a new law would be too politically complicated; the old law would have to do.

When this case made its way to the Supreme Court, Chief Justice John Roberts's majority opinion found the statutory grounding ludicrous. The waiver power being relied on, when understood in its appropriate context and with attention to what Congress was trying to achieve, was meant to give the secretary of education some degree of flexibility in dealing with difficult circumstances confronting Americans who had served their country in the military. It was not meant to be a grant of power to "rewrite that statute from the ground up," leaving the secretary with essentially "unfettered discretion to cancel student loans."

The majority opinion insisted that its rejection of the radical plan was faithful to the idea that Congress must be the one to make big decisions — i.e., that this was a paradigmatic case of what is now known as the "major-questions doctrine." "The question here is not whether something should be done," Roberts wrote, "it is who has the authority to do it."

Justice Kagan, in her dissent, insisted that the majority's concern for Congress was entirely insincere, as demonstrated by its unwillingness to appreciate the contributions of the 108th Congress that passed the HEROES Act. That body, she said, was wise enough to provide for delegated powers sufficient to meet future exigencies — "[e]xcept that this Court now won't let it reap the benefits of that choice." Indeed, in Kagan's telling, if executive-branch officials failed to aggressively wield existing powers, "Congress would be appalled." The major-questions doctrine, in her view, was "specially crafted to kill significant regulatory action, by requiring Congress to delegate not just clearly but also micro-specifically."

As an interpretation of the HEROES Act in particular, Kagan's dissent comes across as borderline delusional. In response to her claim that Congress would be horrified, if one put the question to the legislators who wrote, deliberated on, and passed the HEROES Act in 2003 whether it ought to be able to serve as the basis for complete cancelation of $430 billion worth of loans, Chief Justice Roberts said: "We can't believe the answer would be yes. Congress did not unanimously pass the HEROES Act with such power in mind."

What's more, Kagan's claim that the majority's opinion reduces the HEROES Act to the status of a relatively unimportant law is self-defeating, considering that everyone who had ever heard of the debt-forgiveness provision before the pandemic believed it was unimportant. In support of that proposition, Roberts cited a July 2021 statement from Nancy Pelosi to the effect that debt forgiveness "has to be an act of Congress." At that time, the speaker of the House did not so cherish the HEROES Act as to be offended by the idea that it was inadequate to the task.

Kagan's passion is more comprehensible if we understand her more general aim. As has been clear since the publication of her seminal 2001 article, "Presidential Administration," Kagan believes that the political achievement of 20th-century American lawmakers was to create a vast edifice of governance, one in which the executive branch is empowered to take on all sorts of needed tasks under the direction of the politically accountable president. This is to be regarded as a successful exercise in state building, enabling the energetic statesmanship needed to confront a challenging time.

Given this great achievement, according to Kagan, it matters little if current-day lawmakers dislike what the president is doing: They are probably motivated by nothing more than shallow partisanship. And, in any case, they have nothing to say about the law already on the books — unless, of course, they can rouse themselves to change it, and good luck with that. Past Congresses were wise enough to delegate broadly and demand boldness — we know this to be true because of the statutory text's openness. If we insist on diminishing Congress's words in our reading of them, how likely is it that our current legislators are going to supply the needed sense of responsibility if the president does not? If we deny maximalist interpretations of existing statues, we risk leaving our ship of state utterly listless.

In other words, Kagan's view amounts to something like, "thank goodness past Congresses put lots of elephants in mouse holes, because otherwise, we'd be all out of elephants."

LAWMAKING AND BARRETT'S BOLD BABYSITTER

Justice Amy Coney Barrett wrote a concurrence in Biden v. Nebraska meant to clarify what the major-questions doctrine is really all about. Her argument offers an important but frustrating contribution because it grasps the precise nub of the issue but then obscures it by means of an awkward analogy.

Barrett wanted to clarify what textualism, rightly understood in the 2020s, ought to be. Looking back at the case of the FDA and tobacco, she noted that the agency's assertion of power "would have been plausible if the relevant statutory text were read in a vacuum. But a vacuum is no home for a textualist." Quoting O'Connor's opinion, she argued that the major-questions doctrine brings to bear "common sense as to the manner in which Congress is likely to delegate a policy decision of such economic and political magnitude to an administrative agency." Textualism, therefore, must protect itself against bad-faith maximalist readings of statutory terms. It must ensure that the reading of statutes does not become a contact sport, played for political advantage. And to do so, it must start with a clear-eyed idea of what lawmaking is.

When Congress creates laws, the lawmakers are not to be understood as simply enshrining broad grants of authority to be defined however the president sees fit. By passing the HEROES Act, Congress sought to provide the secretary of education with the flexibility to deal with a particular set of veterans' issues on an ongoing basis. In codifying the power to "waive or modify" the law, it was not setting up the secretary of education as an independent lawmaker. Justice Kagan's saying, "shucks, well, them's the words, that must be what they meant," comes across as willfully naïve about the kind of enterprise that lawmaking is. Just because Congress wants to leave administrators some flexibility does not mean legislators should be assumed to be washing their hands of future responsibility to take up important problems. Lawmaking (at least in America) happens within the context of continuing self-government.

Unfortunately, in trying to elucidate these important points, Barrett also introduced two distractions. The first came from her folksy analogy featuring "a parent who hires a babysitter to watch her young children over the weekend" and gives the sitter a credit card along with the instruction: "Make sure the kids have fun." The babysitter has been given discretion, but would "a multiday excursion to an out-of-town amusement park" be permitted? Barrett says that we would expect more explicit authorization for such a major undertaking.

That seems like a perfectly reasonable assumption. And yet three law professors fielded a full survey designed to test ordinary Americans' intuitions about the babysitter's actions and found that they mostly believed the babysitter would be justified. They spin this as a "gotcha" showing that "common sense" interpretive principles cannot do the work Barrett hopes they can.

Yet all these professors have shown is that Barrett chose her analogy poorly. The justice herself immediately added a caveat to her example, noting that properly interpreting the parent's instruction to the babysitter would require more context about the relationship between the two parties and the interaction itself, none of which is in evidence. But by making us think about all the idiosyncrasies of interpersonal relationships, and how little we know of this imagined situation, Barrett has drawn attention away from the fact that congressional lawmaking has its own dynamics that can be known by all.

For all their variety, Congress's lawmaking activities are a shared social practice that plenty of observers know a great deal about. Unlike the babysitting hypothetical, statute-making is dripping with history and known context. That context can (and should) be brought to bear on our interpretation of the statute's text.

The second distraction relates to the question of whether and how the major-questions doctrine fits within orthodox textualism. Barrett argued that some "substantive canons" of legal interpretation are "in significant tension with textualism" because of their focus on factors external to the statute. The major-questions doctrine, though, is better seen as fitting into a separate set of "interpretive tools" that aids us in understanding what text means "in context."

Harvard law professor Adrian Vermeule attacked this distinction as untenable, concluding that Barrett's norm-based reasoning cannot fit into a defense of "ideological" textualism. He may well be right. Textualism as an "ism," a self-conscious school of thought in the American legal academy, won many fights. But it ought not be regarded as the one and only proper way of thinking about the law.

As Georgetown law professor Jonathan Molot argued nearly two decades ago, textualism's most vehement champions sometimes put themselves at risk of "transforming their own philosophy into an extreme ideology that is at odds with textualism's own core underpinnings." If they fetishize statutory terms to the exclusion of all other considerations, they risk warping the practice of legal interpretation. Barrett's concurrence shows a textualist avoiding this folly. It may well be that she is stretching to argue that all these good interpretative practices fit neatly within textualism, but her deeper counsel — to be attentive to the context of lawmaking — remains. If some people want to call that something other than textualism, so be it.

DEMANDING A CONGRESS THAT MATTERS

We should now ascend from the specifics of the student-loan case to a broader view of where the constitutional separation of powers stands in 2025. The pseudo-textualists of our age, led by Justice Kagan, want us to believe that the 60,000-odd pages of the United States Code have created for us an exquisite machine, carefully calibrated by our wise bygone legislators and capable of meeting nearly every exigency imaginable. If judges paid heed to the broad delegations that Congress has seen fit to inscribe in the law, energetic presidents could take charge of our governance.

The conservatives, including the chief justice and Justice Barrett, instead declare that they believe Congress — a legislative body in which the people's representatives must decide the leading issues of the day — still matters. Notably, they are not wholly against the idea of a strong administrative state that operates with a fair degree of discretion, as their colleague Justice Neil Gorsuch often seems to be. Their defense of this principal goes beyond major-questions cases or those coming out of Democratic administrations — a truth they demonstrated by striking down the first Trump administration's reinterpretation of firearm laws to ban bump stocks as a variety of machine gun in Garland v. Cargill.

In that case, the court's majority (including all six Republican appointees) made it quite clear that Congress could write a bump-stock ban, but denied it had done so through the statute in question. The justices insisted that a law "is not useless merely because it draws a line more narrowly than one of its conceivable statutory purposes might suggest." Quoting an earlier Gorsuch opinion, they explained that "it is never our job to rewrite...statutory text under the banner of speculation about what Congress might have done."

Law professors Jonathan Adler and Christopher Walker have pointed out that this approach will often render the age of the statute and contemporary interpretations important considerations. Other things being equal, new interpretations of antique statutes should be regarded with suspicion, as they are more likely to be the result of executive-branch lawyers' creativity than the organic outgrowth of discretion willed by lawmakers. When it comes to legitimizing government policy, aging statutes cannot bear the weight of elephants in mouseholes, let alone silently swelling black holes.

When considering the harm that bad-faith interpretation can do to our constitutional balance, we need not remain in the realm of hypotheticals: We already live in a country where both political parties routinely accuse one another of open contempt for the law. Presidents Trump and Biden have both been remarkably open in undertaking legal interpretations they had admitted were dubious, including Trump's 2019 declaration of a national emergency to enable reprogramming of various security funds for border-wall construction and Biden's 2021 eviction moratorium.

The expectation that officials will act via reinterpretation of the law now warps our political system's response to even the most salient crises. Consider the crisis at the southern border in the last years of Biden's administration. Republicans in Congress were united in demanding action, while Democrats had come around to the view that their party had erred and needed to mend its ways ahead of the 2024 election. The prospects for border-security legislation seemed hopeful, with the perennial ambition of "comprehensive" immigration reform shelved. Bipartisan negotiations in the Senate showed serious promise. But numerous Republican lawmakers insisted they had no intention of being suckered into making any laws. By their telling, Biden was so sure to misinterpret their words as to make the enterprise fruitless as long as he occupied the Oval Office. Better to simply stall any legislation involving Democrats and fight for Trump's reelection.

Undoubtedly, these legislators feel vindicated by subsequent events. Republican members of Congress cheered Trump when, in his joint address to Congress in March 2025, he expressed his own sense of things: "The media and our friends in the Democrat party kept saying we needed new legislation, we must have legislation to secure the border. But it turned out that all we really needed was a new president." The 119th Congress, in which Republicans control both chambers, may make a push to ensconce in law what they believe to be sound border policies. Then again, GOP legislators may settle for touting Trump's actions and then warning the electorate that putting Democrats in office would ruin everything.

In each branch, there is every reason to believe in the sincerity of public servants who take the mutability of the law for granted, and indeed help make it a normal part of our government's operation. Many talk themselves into the necessity of being bad-faith interpreters because they believe that being good-faith public servants requires no less than a hard-nosed accommodation of the de facto order. This is far from being a contemptible impulse.

And yet, because the order they are reifying is such a bad one, in terms of having a government ever capable of settling on policies that will endure for more than a single administration, we must nevertheless condemn them. They have taken oaths to uphold the Constitution, and that requires that they take the law — and not just the president — seriously.