A Home of One's Own

To many Americans, the housing crisis of 2008 seemed to come out of nowhere. Home values and home-ownership rates had been climbing for nearly a decade, interest rates had been in decline, and a variety of new financing options had emerged to put homes within the reach of millions who could not afford large down payments or standard loans. More than ever, a home seemed like the most sensible of investments — offering the prospect of good returns, economic security, and the possession of a tangible piece of America.

In retrospect, of course, these very trends were part of what produced the crisis. Through a combination of heedless public policy and reckless lending, the benefits of home ownership had come to be exaggerated; the risks and drawbacks had been obscured from public view; and entry into the housing market had become far too easy. The result was a dangerous bubble that inevitably burst — with terrible implications for the broader economy.

But this American inclination to exaggerate the virtues of home ownership — and to make it far too easy to achieve — dates back much further than the past decade. Home ownership has long held a place in the American pantheon, right up there with baseball and apple pie. It has been heralded as the source of countless benefits to individuals and society — as a way to build personal wealth, provide a positive environment for child-rearing, encourage people to be active citizens, and improve neighborhood stability and safety. Yet while some of these benefits are very real, they are not the whole story. And as urban-planning scholar Lawrence Vale has observed, throughout much of American history we have tended to ignore the rest of the story — coming to "view the transition from renter to homeowner as an act of moral deliverance and financial salvation."

From this veneration of home ownership has emerged nearly a century of government policy designed to encourage and support it. Such policy has certainly done much good, but also a great deal of harm, and it should now be brought into better alignment with the realities of ownership — good, bad, and ugly.

THE IDEOLOGY OF HOME OWNERSHIP

The desire for a home of one's own is hard-wired into the American psyche, reaching back to Thomas Jefferson's notion that the independent yeoman farmer would be the backbone of the new republic. In early America, to be a renter was to be dependent on a class of landlords, and so not truly one's own man. And while Jefferson's Federalist adversaries did not agree with him on much, they did on this point; John Adams and Alexander Hamilton worried that if Americans who owned no property were granted suffrage, they would be obligated to support the political whims of their employers or landlords. The tenant-landlord relationship was too reminiscent of feudalism for republican tastes.

This way of thinking endured throughout the 19th century. It was among the motivations that led hundreds of thousands of Americans to settle the western frontier, where — especially after the passage of the Homestead Act of 1862 — a man could own the land he worked to improve. Walt Whitman, as ever, captured the sentiment of the day: "A man is not a whole and complete man unless he owns a house and the ground it stands on."

By the late 19th century, the proper dwelling place for a middle-class family was commonly understood to be the single-family home. These were to be detached houses with a decent amount of land separating them from neighbors — a vision that was grounded in the Anglo-American ideal of the romantic country cottage, and that shaped the development of the early suburbs around major cities. As historians Olivier Zunz and Stephan Thernstrom have noted, home ownership among the working class, too, was surprisingly prevalent in this era — especially in industrial cities like Detroit and coastal towns such as Newburyport, Massachusetts.

Another influential factor was the development of streetcars, which opened up home-owning opportunities outside of crowded cities for both the middle and working classes. As historian Kenneth Jackson has written, when combined with abundant land and the popularity of balloon-frame houses that could be built quickly and cheaply, this meant that, "for the first time in the history of the world, middle-class families in the late nineteenth century could reasonably expect to buy a detached home on an accessible lot in a safe and sanitary environment."

Meanwhile, the idea of middle- and upper-middle-class families renting in large urban apartment buildings came to be frowned upon. At the turn of the 20th century, tenement reformers — like New York's Jacob Riis and Lawrence Veiller — exposed the conditions of overcrowded immigrant ghettos. While much of what the reformers described was surely as bad as they suggested, their observations were also influenced by their personal biases against dense, urban environments. Implicit in their criticism — which helped shape the views of the American elite on the subject — was the notion that the ideal form of housing was the single-family home.

It was around this time, and especially after the First World War, that the belief in the social value of home ownership first found expression in public policy. Federal support began as an extension of anti-communist efforts in the wake of the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia; as one organization of realtors put it at the time, "socialism and communism do not take root in the ranks of those who have their feet firmly embedded in the soil of America through homeownership." A public-relations campaign dubbed "Own Your Own Home" — originally launched by the National Association of Real Estate Boards in the aftermath of World War I — was taken over by the U.S. Department of Labor in 1917, and became the first federal program explicitly aimed at encouraging home ownership. The program was largely promotional; there were no financial incentives offered to prospective home buyers or builders. The Labor Department handed out "We Own Our Own Home" buttons to schoolchildren, sponsored lectures on the topic at universities, and distributed posters and banners extolling the virtues of home ownership and pamphlets on how to get a home loan.

In 1921, the program moved to the Commerce Department, where Secretary Herbert Hoover soon became the nation's foremost promoter of home ownership. "Maintaining a high percentage of individual home owners is one of the searching tests that now challenge the people of the United States," Hoover wrote in 1925. "The present large proportion of families that own their own homes is both the foundation of a sound economic and social system and a guarantee that our society will continue to develop rationally as changing conditions demand."

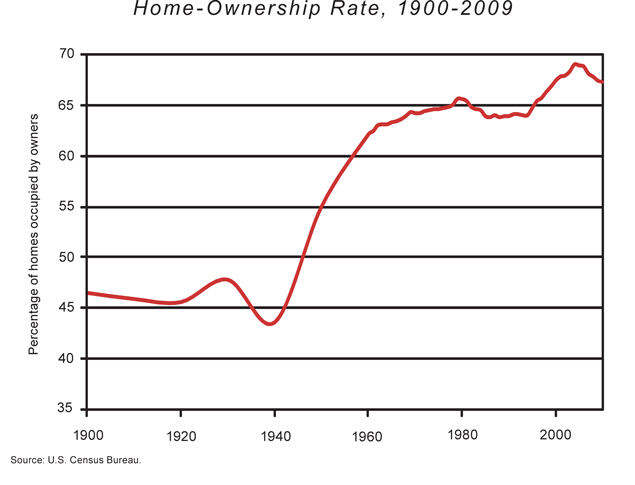

Hoover's role as the nation's chief booster of home ownership was in keeping with his conservative progressivism. He believed in using the power of government, in association with business, to improve society and allow it to "develop rationally." Hoover was responding to a slight dip in the home-ownership rate (a statistic maintained by the Census Bureau that measures the percentage of households that are owner-occupied). By 1920, the rate had declined to 45.6%, from a level of 47.8% in 1890. But this slight drop masked a countervailing trend; in fact, non-farm home ownership was booming after 1890. It was the steady drop in farm-ownership rates that had caused the dip: From 1890 to 1920, the non-farm ownership rate went from 36.9% to 40.9%. Rather than a matter for housing policy, the decline that worried Hoover was part of America's adjustment to a post-agrarian economy.

Nevertheless, Hoover continued evangelizing for home ownership throughout the 1920s. While commerce secretary, he also served as president of the "Better Homes in America" movement initiated in 1922 to celebrate home ownership. (Vice President Calvin Coolidge served as the organization's chairman.) The overall home-ownership rate during the decade reflected, in part, the influence of Hoover's public-service campaign (along with improving economic conditions): Rates increased steadily from 45.6% in 1920 to 47.8% in 1930, while the number of new homes increased by nearly 3 million.

The Great Depression, which began only months after Hoover's inauguration as president in 1929, severely set back the case for home ownership, of course. The economic downturn led to a rise in home foreclosures, totaling a record 193,800 in 1931 — a figure that would only increase in each of the next four years. Overall, home-ownership rates declined from 47.8% in 1930 to 43.6% in 1940. And as more and more people defaulted on their home loans, they placed an added and unwelcome burden on an already dysfunctional banking system.

As a result, the Depression brought about more concrete government action. In his last year in office, Hoover created the Home Loan Bank System, which sought to provide liquidity for financial institutions — especially savings and loan banks — affected by the growing number of people defaulting on their mortgages. The program had little effect in stemming the tide of foreclosures, but it did open the door for further government intervention in the mortgage market.

HOME OWNERSHIP AS PUBLIC POLICY

The administration of Franklin Roosevelt took that intervention much further — and, in the process, radically changed the way homes were financed in America. In his first year in office, Roosevelt created the Home Owners' Loan Corporation to help Americans threatened with foreclosure by transforming short-term loans into long-term mortgages. The agency was designed to purchase the mortgages of home owners at risk of defaulting, and then refinance the loans with more advantageous terms made possible by its government backing. Over the next two years, HOLC refinanced nearly 1 million mortgages. And while about 20% of home owners utilizing HOLC eventually defaulted, the program clearly saved countless others from the same fate by easing their payments and terms.

Yet important as HOLC was, it was really the Federal Housing Administration and the Federal National Mortgage Association (Fannie Mae) — created in 1934 and 1938, respectively — that redefined the way Americans purchased their homes. Originally designed to boost home construction, the FHA's real impact was in the way it changed the average home mortgage. Prior to the 1930s, home buyers were generally offered short-term mortgages lasting from five to ten years and covering only about 50% of the cost of a house (the rest had to be put up in cash, making the purchase of a home an enormous up-front investment). But starting in the mid-1930s, the FHA offered insurance to lenders for mortgages that met certain criteria (like a minimum down payment or borrower income). This lowered the risks of lending, thereby lowering the cost of lending and allowing banks to offer home buyers better and longer mortgage terms.

The new norm — one that would endure for decades — came to be the fully amortized 20- to 30-year mortgage covering 80% of the cost of the house. These new mortgages drastically reduced down payments and regular monthly payments, and were so popular that even lenders not making FHA-backed loans brought their mortgages into line with the new terms. Moreover, as many of the risks of lending diminished, buyers also started benefiting from a decline in mortgage interest rates. The result was a revolution in the housing market.

To further reinforce these long-term loans, Congress created Fannie Mae. Originally a government agency (until 1968), its purpose was to encourage a secondary mortgage market that would help provide lenders with greater liquidity, and so encourage more home loans. Since long-term mortgages are paid off slowly over decades, they can limit a lending institution's cash on hand, and so keep the institution from making any additional loans. Fannie Mae's goal was to purchase long-term mortgages from these lenders — initially using taxpayer funds, and later with its own revenues — thereby providing the lenders with the cash they needed to offer more loans. The company would then turn the long-term mortgages into securities, which it could sell to raise more funds.

Fannie Mae and the Federal Housing Administration — combined with the Veterans Administration-insured mortgages created by the G.I. Bill after World War II — helped to create a post-war building and home-ownership boom. Other, more modest incentives — most notably the deductibility of loan interest from federal income taxes — further advantaged owners over renters. And between 1940 and 1960, the home-ownership rate in the United States increased dramatically — from 43.6% to 61.9%.

In many ways, this system proved to be a great success — helping to build a home-owning middle class, and driving the post-war economic boom. But even early on, there were dissenters. In 1945, sociologist John Dean published the book Home Ownership: Is It Sound? "The problem of home ownership, like the rest of the ‘housing problem,' will presumably someday be faced squarely by the United States," Dean wrote. "When that time comes America will no doubt look back on our own time as an era in which society encouraged its families to stride ahead through a field deliberately sown with booby traps." But while default rates for FHA-insured mortgages were higher than those for other loans, the booby traps that Dean worried about — home owners enticed to enter into loans they could not possibly repay — would not fully materialize for decades.

In the meantime, the policies of the FHA created other problems. Along with providing mortgage insurance, the agency established underwriting standards for loans, including a stricter and more uniform set of housing-appraisal guidelines. Key to those standards was a geographically based rating system that evaluated whether homes were worthwhile investments and whether residents were credit worthy. From the beginning, this system reeked of discrimination: Neighborhoods populated by well-off white Protestants received the highest grades; those populated by lower-income racial and ethnic minorities received the lowest. One FHA underwriting manual in the 1930s even listed "infiltration of inharmonious racial or nationality groups" as a risk factor to consider in a neighborhood's assessment.

The FHA was influenced by the work of the Home Owners' Loan Corporation, which had created elaborate maps of neighborhoods throughout the country. HOLC's maps were divided into four categories, labeled A through D and also color-coded, based on the residents' perceived credit worthiness. Neighborhoods labeled "D," and so deemed riskiest for lending, were color-coded red; thus the FHA's strict lending guidelines, which employed the same maps, eventually became known as "redlining."

Some argue that the lending policies of the FHA turned its appraisal maps into self-fulfilling prophecies, as residents of lower-income, urban communities found it more difficult to borrow money, thereby accelerating urban poverty and social decay. A number of academic experts over the years have laid much of the blame for the decline of the American city at the feet of these FHA practices, arguing that the agency skewed lending toward the suburbs and away from cities. They also note that FHA policies especially harmed African-American communities by preventing residents from borrowing money to buy or renovate homes.

While there is certainly some merit to this argument, it is hardly a complete explanation of the crisis in America's inner cities. Black home-ownership rates did lag far behind those of whites, but still increased steadily in the post-war years — from 22.8% in 1940 to 38.4% in 1960. Moreover, working-class white neighborhoods were often classified as lending risks too, but generally did not see the same kind of turmoil and decline. There was certainly more troubling America's cities in the 1950s and '60s than differential lending practices.

Nevertheless, the FHA surely made lending in urban areas more difficult, and was not shy about tying its decisions to race and ethnicity. By the mid-1960s, in the midst of the civil-rights era, it was clear that such practices could not continue. The effort to reform them — led by Senator Charles Percy, an Illinois Republican — involved expanding access to home loans, making them available to areas and individuals known to be potential default risks. "The promise of homeownership provides a meaningful incentive to the initially lower-income family to spur its efforts to climb the ladder of economic security and responsible citizenship," Percy said. His move may have been driven by concerns about civil rights, but it was also spurred by a fear of the racially charged urban riots then plaguing American cities. Home ownership was seen as a way to give inner-city minorities a stake in their communities, and so to quell the more destructive manifestations of their anger. The feeling at the time was that people would not burn down houses that they owned.

In 1965, Congress created the Department of Housing and Urban Development — a new cabinet-level agency designed specifically to contend with urban housing issues. And in 1968, at Percy's prodding, the department established a new program under the FHA (known as Section 235) to give low-income urban residents heavily subsidized mortgages. Buyers had to contribute a nominal down payment, no more than a few hundred dollars, and low interest rates subsidized by the FHA substantially reduced their monthly payments. Over the next four years, HUD would provide roughly 400,000 mortgages under the program.

But Section 235 ran into problems from the start. It was poorly administered, and corruption among FHA inspectors was widespread. It also spurred an epidemic of panic selling in cities across the country: Speculators and real-estate agents drummed up fears among white home owners that poor minorities using the new FHA loans would overtake their neighborhoods. Many whites sold their homes, in part because they feared a decline in property values. Speculators then got corrupt appraisers to inflate the value of these homes and sold them to minority families at inflated prices — with the purchase almost completely subsidized by the federal government. The Manhattan Institute's Steven Malanga has described what followed as "not urban uplift but urban nightmare."

Unsurprisingly, foreclosures increased, neighborhoods quickly turned into ghettos, and HUD ended up owning thousands of urban properties that were nearly worthless. According to Malanga, there were almost 4,000 Section 235 foreclosures just in the city of Philadelphia between 1969 and 1971 — more than the total number of FHA foreclosures in the city since the 1930s. In the early 1970s, congressional investigations laid out Section 235's whole sorry story, and shortly thereafter Congress forced HUD to shut it down.

There would be no going back to the original discriminatory FHA practices in the post-civil-rights era, of course, so the question of how to increase lending in urban neighborhoods, especially poor and minority neighborhoods, remained. By 1980, the overall home-ownership rate was above 64%, but politicians of both parties did not give up on the dream of taking it higher. And their focus, more than ever, was on closing the gap between white and minority ownership.

HOPE AND HOUSING

Before the compassionate conservatism of George W. Bush, there was the empowerment conservatism of Jack Kemp. As a member of Congress in the 1970s and '80s, and as secretary of HUD under President George H. W. Bush, Kemp made it his mission to broaden the reach of the Republican Party beyond the white middle class, reaching out to minorities and the poor. Home ownership was a special passion of Kemp's, and as HUD secretary in particular, he pursued tenant ownership of public-housing units as a way to close the racial gaps in home ownership.

Kemp was evangelical in his mission to "put assets in the hands of the poor." Tenant ownership, according to Kemp, would "save babies, save children, save families, and save America." His most visible partner in this campaign was Kimi Gray, head of the Kenilworth-Parkside Resident Management Corporation (KPRMC), which oversaw a public-housing project in Washington, D.C. Kemp and Gray were going to make the residents of Kenilworth-Parkside — and of public-housing projects across the nation — owners of their homes. Kemp called his program Home Ownership for People Everywhere (HOPE).

His plan melded the traditional ideology of home ownership with the new Republican politics of the "opportunity society," which was the GOP's answer to the War on Poverty. But whatever the merits of Kemp's original plans, their implementation was largely a failure. When Kemp managed to engineer the sale of Kenilworth-Parkside, it was merely turned over to the KPRMC, which oversaw the project. The renovation of the housing units proved immensely expensive, yet in the end tenants never actually got to purchase their apartments. The plan was deemed unfeasible and ultimately scrapped, killing hopes that it would be followed as a model by other public-housing projects around the country.

While Kemp's optimistic, passionate style made him a welcome voice in the GOP, in the end his policies did little to expand the party's base. Poorly designed programs fed the idea that this was more of a political gimmick than a thoughtful response to social problems.

The Clinton administration pursued an even broader and more ambitious agenda of encouraging home ownership. "I want to target new markets, underserved populations, tear down the barriers of discrimination wherever they are found," Bill Clinton told the National Association of Realtors in 1994. His answer was the National Home Ownership Strategy — and his tool was Fannie Mae.

Clinton's logic was straightforward: If the combination of the FHA and Fannie Mae had worked so well in opening up lending for middle- and working-class Americans after World War II, why not use these and other government instr uments to help lower-income Americans move into their own homes? Although Fannie Mae had been turned into a publicly traded company in 1968, it was still chartered by Congress — and so enjoyed the implicit promise of government backing in a crunch, which allowed the company to benefit from low interest rates. And in 1970, to avoid allowing Fannie Mae a monopoly position and to expand the secondary mortgage market, Congress had created a companion entity, the Federal Home Loan Mortgage Corporation. Known as Freddie Mac, the company was understood to have the same implicit government backing (and the benefits that came with it). Because both companies were so closely tied to government, and hence vulnerable to pressure from policymakers in Washington, they were ideally positioned to help Clinton pursue his home-ownership agenda.

Clinton's first HUD secretary, Henry Cisneros, pushed the two "government-sponsored enterprises" toward requiring that 40% of all the mortgages they traded originate from low- and moderate-income borrowers. Cisneros's successor, Andrew Cuomo, pushed the benchmark to 50%.

But Fannie and Freddie don't originate loans; they simply purchase them from lenders and repackage them into securities. So the second step in the Clinton administration's plan was to "partner" with lenders who would promise to make more loans based on liberalized terms to lower-income home buyers, in exchange for better terms from Fannie and Freddie. Countrywide Financial, which would later become synonymous with the excesses of the subprime market, was the first to sign up for the partnership.

Countrywide's CEO, Angelo Mozilo, was above all a shrewd businessman interested in maximizing his company's profits — though he was also clearly committed to his company's mission: "Help All Americans Achieve the Dream of Homeownership." Bill Clinton believed the same thing. According to journalist Alyssa Katz, "Clinton saw few bounds to the power of homeownership; to set wayward young people on a course to success, to turn slums into orderly communities, to accomplish with a few pieces of paper what three decades of welfare had failed to do."

The problem was that all of these policies were based on little except a firm and sanguine belief in the value of home ownership. "The validity of some of these assertions [about the benefits of home ownership] is so widely accepted that economists and social scientists have seldom tested them," declared a 1995 HUD report. When social scientists did begin to look at the evidence, they found little to confirm that any serious benefits accrue to low- and moderate-income home owners. If home ownership had such magical properties, then West Virginia would be the most stable and prosperous state in the union, as it has had the highest percentage of home owners of any state since 1980.

The mortgage lenders, however, were certainly benefiting from this illusion and the arrangements it had spawned, as were the officers of Fannie and Freddie. Clinton's housing policy also produced a political windfall for him — it was the ultimate "Third Way" idea, satisfying traditional Democratic constituencies with its expanded and liberal lending policies, but also pleasing more conservative bankers and realtors. The 1990s saw home-ownership rates rise from 64.2% to 66.2%.

So when George W. Bush took office in 2001, his housing policy was essentially an extension of his predecessor's. The new administration made expanding home ownership — especially for minorities — a key priority, and made praise for the "ownership society" a regular feature of the president's rhetoric. Bush set a goal of creating 5.5 million more minority home owners by 2010; to reach it, the administration increased Fannie Mae's targets for lower-income mortgages to 56%.

But as lenders tried to reach riskier borrowers, they ran into difficulty. As Bush often noted in speeches, one of the biggest barriers to home ownership was the inability of prospective home buyers to afford a down payment. The administration created the American Dream Downpayment Fund to provide $200 million annually to assist home buyers, but its relatively small size meant that it was almost a purely symbolic gesture, making very little difference in practice. Far more important were the efforts of the lenders themselves to help borrowers overcome the hurdle of a down payment.

More and more mortgages were offered with little or no down payment required; some people even borrowed more than the value of the home they were buying to help pay for closing costs. Lenders like Countrywide also came up with creative options for reducing the burden of paying back loans, including interest-only payments. Short-term adjustable-rate mortgages and introductory teaser rates also helped lower monthly payments — though only temporarily.

Lenders kept lending, granting increasingly sizable mortgages and increasingly generous terms to increasingly risky borrowers. They could get away with it because the loans would quickly be sold off to Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, and most were eventually repackaged and sold off as securities. Most analysts at the time argued that this process both provided added liquidity and accurately assessed the risk of the loans, spreading that risk out over the market.

On the ground, however, all of this meant that more and more borrowers had little to no equity in their homes. Their saving grace was the ever-rising housing market. Thanks to interest rates kept artificially low by the Federal Reserve in order to encourage economic growth after the September 11th attacks, housing prices took off — and home owners paid little attention to the specifics of their mortgages or their debts, fully expecting to refinance as their houses appreciated in value. By 2004, the home-ownership rate hit 69%.

This housing bubble was bound to burst. When it did, many home owners were saddled with debts larger than the value of their homes. Foreclosures exploded, rippling across the economy and affecting institutions and investors who held the increasingly complex securities based on the bad mortgages.

Looking back, it is easy to see how the policies of the Clinton and Bush administrations contributed to the inflation and the bursting of the housing bubble. But these problems were much more than 15 years in the making. Clinton and Bush were simply following out the logical trajectory of the ideology of home ownership, advancing the policies of their predecessors. Like many others before them, they assumed with little evidence that home ownership would be a panacea. They believed that government backing of the mortgage market would reduce costs and increase liquidity. And they believed that the dangers of the riskiest mortgages could be adequately spread out across the market and measured by investors. They were wrong, of course — and now all of us are paying the price.

The financial crisis that followed the bursting of the housing bubble should force us to step back and re-examine our policies and attitudes toward home ownership. On its face, even despite the crisis and the earlier distortions of the housing market, government encouragement of home ownership achieved its key goal. The home-ownership rate increased from 43% in 1940 to 69% in 2005 (although it has since returned to roughly its 1990 level of just above 66%). That increase was due in large part to government policies that provided easier access to credit, supplying more Americans with the money they needed to buy homes. Prior to the recent housing troubles, this had occurred at relatively little cost to the taxpayer.

And yet, from the beginning, there has been an inherent contradiction in federal housing policy. Programs that encouraged home ownership have also helped to increase housing prices. Add to this mix low interest rates, the home-mortgage tax deduction, and land policies designed to halt sprawl, preserve open spaces, and protect the environment, and the result has been a set of government policies that have exerted upward pressure on the price of housing. If federal housing policy had been essentially intended to help build (and protect) equity for home owners, then this would have made sense.

But the steady rise in housing prices also made it more difficult for non-home owners to buy their first homes. This necessitated policies designed to assist first-time home buyers by lowering the costs of entry into the housing market. Over the years, housing policy thus became something like a dog chasing his own tail. Encouraging home ownership would drive prices up, but the more expensive homes got, the more difficult it became to enter the housing market, driving the government to loosen lending standards and let more buyers into the market. The cycle continued and the bubble grew.

It makes little sense now to simply persist in this cycle, or to imagine that the logical conclusion of the ideology of home ownership — the notion that every American family should own its home — is anything but a ridiculous fantasy. There is of course no magic number for the proper percentage of home owners, and yet in the final years of the recent housing boom, mortgage lenders were increasingly scraping the bottom of the lending barrel to help attain some nebulous ownership goal. Policymakers in the aftermath of the crisis cannot encourage those practices to continue; it is time to declare a moratorium on new federal programs intended to encourage home ownership.

In recent months, a number of commentators from across the political spectrum have been voicing just this sentiment. "The New American Dream: Renting" read the headline of a Wall Street Journal op-ed by historian Thomas Sugrue last year. A few months earlier, New York Times columnist Paul Krugman wrote that "you can make a good case that America already has too many homeowners." Eric Belsky of Harvard's Joint Center for Housing Studies wrote in the Los Angeles Times recently that "the bloom is already off the homeownership rose," adding that it is time to "make homeownership just one alternative in a more innovative, affordable and broader housing market."

For Belsky, at least, this view marked a notable change of heart. In 2002, he and his colleague Nicolas Retsinas co-edited a volume on low-income home ownership in which they explicitly encouraged the idea. Worried that only 52% of low-income Americans owned their own homes, Belsky and Retsinas argued: "We can, and should, aim higher." A lot has changed in the few years since those words were written.

Will Washington change its attitude, too, and pull back from its infatuation with boosting home-ownership rates? The early indications are not heartening. The new $8,000 tax credit for first-time home buyers is a return to earlier efforts to try to re-inflate the housing market by (artificially) stimulating demand. Politicians still seem to think that we can recover from the recent market crash simply by pumping air into the next bubble.

Powerful political interest groups on both sides of the aisle are also pushing for the blinders to be put back on. The National Association of Realtors, the Mortgage Bankers Association, and the National Association of Home Builders — all of which tend to support Republicans — serve as powerful cheerleaders for inflating the housing market. And community-action groups, the Congressional Black Caucus, and civil-rights organizations — mostly on the left — have also firmly opposed efforts to tighten lending policies. They see a loosening of credit as a way to redress the decades of discriminatory patterns in lending that led to "disinvestment" in inner-city minority communities.

But no matter the political or economic exigencies, there is simply no excuse for ignoring the lessons of the past two years. Those lessons don't point toward a policy of contracting the housing market; they do, however, call for moderation, for an awareness of risk, and for taking a few reasonable steps to bring our housing policy more in line with social and economic reality.

First, the federal government should encourage (through its regulation of lenders) a return to more standardized mortgage packages, in particular 30-year fixed-rate mortgages with significant down payments of at least 10 to 20%. The days of exotic and risky borrowing schemes — like interest-only mortgages, short-term adjustable rates, or loans that require little or no down payment — should be a thing of the past. Buying a house represents a significant transaction, with significant responsibilities and significant debt; our policies should treat it that way. There is a fine line between reasonable policies to increase mortgage lending and opening wide the floodgates of credit — a line the federal government pushed banks to cross. It should now help pull them back.

Second, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac should not simply return to their pre-crisis incarnations. The two companies were taken over by the federal government in September 2008, and the Treasury confirmed (as the mortgage market had always assumed) that it would back the mortgages they held or guaranteed — which by the end of 2008 amounted to some $1.6 trillion of high-risk debt. Clearly, Fannie and Freddie's status as privately owned, for-profit companies that nonetheless possessed implicit federal backing was fraught with disaster. Most of the financial benefits created by these government-sponsored enterprises went to the officers of the companies instead of borrowers, while all of the risks they took on were ultimately borne by taxpayers.

There is no question that the housing market requires a functioning secondary mortgage market to provide the liquidity needed to make long-term mortgages viable. The Obama administration has so far insisted that such a market would require some kind of government-sponsored enterprise like Fannie or Freddie, albeit with protections against the distortions and abuses exposed by the crisis. Yet it would be hard to avoid these problems as long as the firm involved continued to blur the lines between public and private. Policymakers should look to empower private-sector firms to perform these functions instead, perhaps supplying some government-backed catastrophic insurance or re-insurance as a cushion.

Third, the home-mortgage deduction — beloved by the public, detested by economists — should gradually be curtailed. While the deduction seems not to affect home-ownership rates a great deal, it does have the effect of increasing home prices. And through the deduction, the government not only directly subsidizes home owners at the expense of renters, but also subsidizes mostly upper-income home owners. Only half of home owners take advantage of the deduction by itemizing their tax returns, and nearly half of the benefits go to people making more than $100,000 a year. In 2006, the cost of the deduction to the Treasury — meaning the rest of the taxpaying public — was $76 billion.

Most people forget that Congress never created a specific tax deduction for mortgages. From the earliest years of the federal income tax, all forms of interest were tax deductible. But during the tax reforms of the 1980s, those deductions were abolished — with the exception of the popular deduction for home mortgages. So today, people can no longer deduct credit-card interest, but they can take out a line of home equity of $100,000 to purchase what they wish and then deduct that interest from their taxes.

While an outright abolition of the mortgage deduction is probably all but impossible politically, the current cap of $1 million should gradually be lowered. That would both help ease the federal deficit a little and reduce some distortion in the real-estate market.

Finally, the housing crisis suggests a deeper and more complicated problem: the role of debt in American life. One hundred years ago, most Americans frowned upon debt. Credit cards and student loans did not exist, and large mortgages were rare. It wasn't until the latter half of the 20th century that America saw an explosion of increasingly easy and cheap consumer credit, and so also of consumer debt.

When handled reasonably, debt is a useful tool of upward mobility. Most Americans could not buy cars or homes without borrowing significant sums of money, and the age of consumer debt has mostly been an age of economic growth and rising standards of living. Yet saddling people on the economic margins of society with large mortgages turned out to be a bad idea for borrowers, lenders, and the country as a whole. Housing policies not only encouraged people to buy homes they could not afford, but also encouraged home owners to borrow substantial sums of money against the value of their homes as the housing bubble drove prices higher. What followed was an orgy of debt-fueled consumption: Between 2000 and 2007, home-equity withdrawals for personal consumption totaled $2.8 trillion.

The rise in personal debt has been mirrored by a similarly dangerous wave of red ink on the balance sheets of federal and state governments. The politics of the next decade will be preoccupied with restoring fiscal sanity to both public and private finances. In that environment, it will not make sense to keep encouraging individuals to go deeper into debt.

Indeed, the question of debt in American life brings us full circle to the ideology of home ownership. If the Jeffersonian ideal was a nation of yeoman farmers independent of a landlord class, immense indebtedness is hardly its realization. Today many Americans may own their own homes, but they do so at a very high cost to their independence — encouraged by a century of public policy to exchange the status of a renter for the status of a debtor.

BACK TO REALITY

No matter what the federal government does, the desire to own a home will continue to burn in most Americans' hearts. That desire is an inseparable piece of the larger American Dream, and it generally makes good practical, social, and economic sense. Nor is it reasonable to expect government to abandon completely its role in the housing-credit markets, which are essential to the nation's economic health.

But it is time to start reminding ourselves that the dream must be tethered to reality. If we are honest, we will acknowledge that home ownership is not for everyone, and that renting is a perfectly reasonable — in fact, preferable — option for people in some circumstances. It is simply not rational to expect that the line on the home-ownership chart can or should keep rising until it reaches 100%.

As John Dean wrote 65 years ago, "For some families some houses represent wise buys, but a culture and real estate industry that give blanket endorsement to ownership fail to indicate which families and which houses." In 1945, Dean was bucking the tide. But in the wake of the Great Recession, his wise words offer a message that our policymakers need to hear once again.