A Cultural Agenda for Our Time

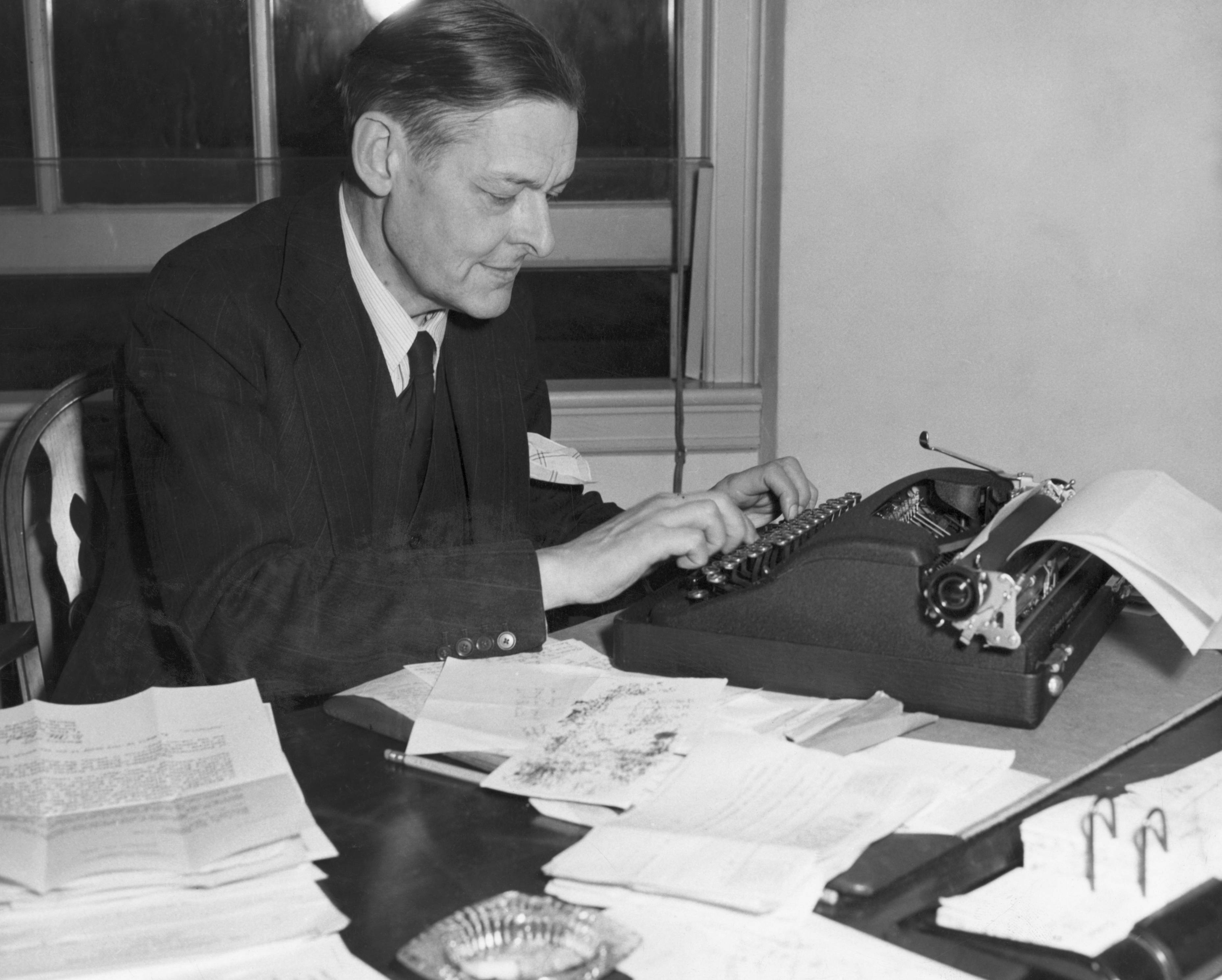

One friday afternoon in November 1948, T. S. Eliot opened a new chapter in American culture policy. Eliot, just two weeks removed from winning the Nobel Prize in Literature, spoke at the invitation of the Library of Congress on Edgar Allan Poe's significance as a poet. He derided Poe as immature and sloppy — his kindest comment was that Poe was at heart a "displaced European" — but found it significant that the French symbolist poets Baudelaire, Mallarmé, and Valéry all drew extensively on Poe. Poe's careless style-over-substance approach, Eliot explained, looked to the French symbolists like an avant-garde forebear of la poésie pure — the point at which subject matter would cease to matter, while poetic technique, theory, and the artistic process in itself would be all-important. Valéry in particular held up the individual artist and his artistic process as the ideal central concern of any artistic "content." Eliot lamented this development, but nonetheless saw it as the legitimate and historically inevitable development of Western poetry. To reject la poésie pure "would be a lapse from what is in any case a highly civilized attitude to a barbarous one."

Eliot's acceptance of this highly technical direction in modernism, and the subordination of an American poet to French preferences, reflected his experience as an expatriate. Many in his audience were similarly cosmopolitan poets, but not all. Those poets in the audience more engaged in the domestic American tradition were indignant — not because they had special affection for Poe, or even disagreed with Eliot's characterization, but because they saw the lecture itself as an official government endorsement of Eliot's prognosis. The Library of Congress had, in their view, sponsored a lecture that conceded to the French the trajectory of Western poetry as a whole, and considered American poetry insignificant except insofar as it could copy European trends. The federal stamp of approval on Eliot's (admittedly begrudging) acceptance of an artist-focused, highly technical European development rubbed them the wrong way.

One of these disgruntled audience members, the poet Charles Olson, described the event sardonically as "the coming to Washington (as tho to Rome) of the 'Poets.'" Eliot's lecture "was like a laying on of hands, the coming into existence of an American poet laureate; the creation, and the turnover, of the 'poets of Congress,' the Consultants." To Olson, the lecture represented a show of political allegiance on Eliot's part, and, on the government's part, an elevation of Eliot's views to the status of officially sanctioned art, not for any artistic interest but for its own.

William Carlos Williams offered a more thorough, and more personal, criticism of Eliot's new position as "American poet laureate." Williams and Eliot had long represented two oppositional strains in American poetry. While Eliot had expatriated himself to the United Kingdom after the First World War, Williams (a small-town New Jersey doctor) spent his entire career in the United States. Eliot and Williams shared influences, most notably their mutual friend Ezra Pound, and used poetry to address some similar problems, such as the rootlessness of modern life. Eliot dealt with that rootlessness by uprooting himself in search of a deeper-rooted European tradition than his St. Louis home could supply, while Williams turned to local experience as a poetic resource, writing from a perspective of intense attention to details and to people. Williams knew that his American roots were shallow, but believed it was possible to deepen them with time and attention.

From Williams's perspective, Eliot's Eurocentric traditionalism undermined the project of deepening American roots by encouraging poetic trends that contravened the burgeoning American tradition. The Waste Land, Eliot's 1922 masterpiece, amazed and disturbed Williams for this very reason. He called it, in his autobiography, a "great catastrophe to our letters." The project of developing a democratic American tradition rooted in local experience "staggered to a halt for a moment under the blast of Eliot's genius which gave the poem back to the academics. We did not know how to answer him." The Waste Land set the tone for modern poetry — an academic tone, stuffed with references to a European tradition that most lay people, especially lay Americans, couldn't claim without joining Eliot in uprooting themselves, and despairing of the modern world in which Americans had to learn to live.

Williams saw in Eliot's 1948 lecture a reminder of The Waste Land's brilliant cosmopolitan pessimism, and had a similar reaction. He responded with a lecture of his own, delivered at the University of Washington and later published as "The Poem as a Field of Action." In it, he took the opportunity to outline his own view of where poetry might go. Instead of a shift from subject to technique, Williams foresaw a broadening of both. He argued that poetry could respond to modern life by becoming more capacious. Indeed, the job was already halfway complete, as American poets (like himself) already explored subject matter once thought too grubby and trivial. The remaining task would be to similarly expand poetic structure, and the only place this development could happen, Williams argued, was America — a young nation that offered a "new language" for creativity.

Such an expansion would require building up the American domestic pool of work, a humble but necessary task: "We seek profusion, the Mass — heterogeneous — ill-assorted — quiet breathless — grasping at all kinds of things — as if — like Audubon shooting some little bird, really only to look at it the better." Instead of contributing to this domestic body of work, Eliot retreated to English tradition, and that retreat made him pessimistic. Engagement with European tradition made Eliot a great poet, but also made clearer to him the fact that he could do nothing about the modern rupture, that he could only sit back and watch European poets march toward modern forms he couldn't abide. Williams described Eliot's career:

Now when Mr. Eliot came along he had a choice: 1. Join the crowd, adding his blackbird's voice to the flock, contributing to the conglomerate (or working over it for his selections) or 2. To go where there was already a mass of more ready distinction (to turn his back on the first), already an established literature in what to him was the same language (?) an already established place in world literature — a short cut, in short.

Williams made a counterintuitive suggestion — by staying in America and building up a "mass" more closely identifiable with his local, or even national, context, Eliot could have had more agency over the direction of modern poetry than he ever had as a global celebrity. From the latter position, Eliot could only watch and lament as figures like Valéry dictated the future of poetry. The great forces of modern civilization that gave Eliot so much grief could be resisted only at the smallest, most localized level. Williams assured his audience that while Eliot withered abroad, shrinking further into the esoteric and academic, the localist work would continue at home: "[W]e are making the mass in which some other later Eliot will dig."

But it was Eliot's cosmopolitanism that became, for 70 years and counting, national culture policy. The federal government naturally saw value in Eliot's transatlantic poetics — Eliot represented the culture of a new internationalism; his work could be identified not with America in particular, but with Europe, the Free World, the West (as opposed to the totalitarian East) as a united whole. In the immediate postwar period, the United States had a clear interest in identifying itself with a rebuilding Europe, and increasingly an interest in identifying itself as the champion of artistic innovation, of la poésie pure that Eliot had described (if begrudgingly) as the height of civilized poetry.

Allowance for the avant-garde made for an easy contrast with Soviet propaganda, and a cosmopolitan, avant-garde strand of modernism would, as Williams and Olson suspected, dominate the official approach to the arts. Indeed, the rise and decay of that Cold War approach to public patronage of the arts mirrors a number of other important policy debates, and the results might come to vindicate Williams's perspective.

CULTURE POLICY AS FOREIGN POLICY

It's far from common knowledge that the United States ever had a cultural policy, much less that it currently has one. Conservatives and radicals alike might join Olson in recoiling at the very idea of federal entanglement with the arts, thinking it would mean the proliferation of state propaganda (as, admittedly, it often has, even in America).

Eliot's 1948 lecture was not the first time the federal government took an interest in promoting a certain view of American culture, but it did represent the opening of a new chapter in the story of the relationship between our politics and culture. Following the Second World War, the government took steps to promote American culture (or rather, a certain vision of it) overseas to create solidarity with a rebuilding Western Europe. But a larger concern, and one which became more acute as the Cold War dragged on, was to establish a cultural contrast between the free West and the totalitarian East. This was where former expatriates like Eliot came in handy — celebrity artists who already had credibility in Western Europe — and why a lecture that established continuity between American and French poetry (giving priority to the latter) was worth public patronage.

During the mid-20th century, culture policy was foreign policy. Before the National Endowment for the Arts and National Endowment for the Humanities, the agencies that executed American culture policy were the State Department and the Central Intelligence Agency. The State Department's primary contribution was a series of art and music tours around Europe. In 1946, it purchased 79 contemporary paintings, including works by Georgia O'Keeffe, Edward Hopper, and Arthur Dove, for an art show that went to Prague, Brno, and Bratislava, but the show was canceled before completion.

More successful were State Department-funded concert tours for musicians like Duke Ellington and Dizzy Gillespie. Historian Michael Kammen wrote that jazz tours in particular "achieved undeniable popularity wherever they went, and they were perceived as the music of individualism, freedom, pluralism, and dissent — fundamental qualities obliterated by communism." The contrast with communism was key, and it also motivated the CIA's involvement in culture policy. The CIA famously backed the Congress for Cultural Freedom, an international organization launched at a 1950 conference in West Berlin to organize anti-communist intellectuals. The CCF held conferences, published journals, and sponsored exhibitions in 35 countries; Raymond Aron, Sidney Hook, James Burnham, Arthur Schlesinger, Irving Kristol, Bertrand Russell, and many others were involved at various points in its formation and operation.

An agenda of "individualism, freedom, pluralism, and dissent" meshed well with the ethos of mid-century American criticism. Leading liberal intellectuals in New York established academic cosmopolitanism as anti-communism, and a number were involved in the CCF. Art critic Clement Greenberg set the tone for mid-century criticism — he demanded that art remain abstract and independent from the political realm and avoid being "about" anything. "Art for art's sake" was the prevailing doctrine. The instincts Eliot described as la poésie pure migrated into painting with the emergence of abstract expressionism, lauded by Greenberg for its focus on the individual artist's process and technique.

Rumors of CIA involvement with the CCF began to spread in the mid-'60s and were eventually confirmed in a 1966 New York Times report. This led policymakers to establish new agencies dedicated openly to carrying out a national cultural agenda, rather than continuing to promote cultural freedom covertly. Leading liberal intellectuals were keen on the idea. As early as 1960, Arthur Schlesinger was calling for such an agency. His essay "Notes on a National Cultural Policy" argued that "[g]overnment is finding itself more and more involved in matters of cultural standards and endeavor" through such initiatives as "the poet at the Library of Congress, the art exhibits under State Department sponsorship, the cultural exchange programs — these represent only a sampling of federal activity in the arts. If we are going to have so much activity anyway," it might as well be consolidated into a single agency. It would be dedicated to the neutral promotion of art per se, as defined not by any political interest but by artists themselves:

Nor is there reason to suppose that this would necessarily end up in giving governmental sanction to the personal preferences of congressmen and Presidents — e.g., making Howard Chandler Christy and Norman Rockwell the models for American art. Congressmen have learned to defer to experts in other fields, and will learn to defer to experts in this....[T]he role of the state can at best be marginal. In the end the vitality of a culture will depend on the creativity of the individual and the sensibility of the audience, and these conditions depend on factors of which the state itself is only a surface expression.

Lyndon Johnson signed the National Foundation on the Arts and the Humanities Act in 1965, establishing the National Endowment for the Arts and the National Endowment for the Humanities. The new agencies, by merit of being domestic agencies, represented a homeward shift but not a fundamental change in Cold War cultural priorities. Schlesinger's assumption that, by deferring to experts, political interest would be prevented, obscured the fact that the federal government's political interest in art during the Cold War was precisely deferral. The new agencies furthered the broader project of contrasting the free United States with the oppressive Soviet Union not by identifying the former with Europe and the West broadly (except insofar as establishing an arts agency was a conscious imitation of "current experiments in government support of the arts in Europe," as Schlesinger put it), but by showcasing individual freedom of expression.

The National Foundation Act gave the NEA and NEH broad discretion about what to support — their stated objective was "to develop and promote a broadly conceived national policy of support for the humanities and the arts in the United States." The NEA and NEH were founded primarily as grant programs, meant only to promote "American creativity" and "professional excellence" and works of "significant merit," "irrespective of origin." The goals of the State Department- and CIA-backed agenda remained: "[A] climate encouraging freedom of thought, imagination, and inquiry" was an important public priority because "[t]he world leadership which has come to the United States cannot rest solely upon superior power, wealth, and technology, but must be solidly founded upon worldwide respect and admiration for the Nation's high qualities as a leader in the realm of ideas and of the spirit."

One reason it's unclear that the United States government has a cultural policy at all is that the official stance has been artistic autonomy — that is, the government has had to make a good show of being hands-off. In the late 1960s, UNESCO organized a roundtable on global cultural policies and commissioned booklets about state culture programs from countries around the world. Ahead of the roundtable, the American delegation insisted that "[t]he United States has no official cultural position, either public or private"; in the booklet published afterward, it stated, "The United States cultural policy at this time is the deliberate encouragement of multiple cultural forces in keeping with the pluralistic traditions of the nation, restricting the federal contribution to that of a minor financial role." But having an official policy of laissez-faire is not the same thing as not having a policy. Just as in economics, laissez-faire is a substantive ideology, especially given the massive priority of establishing a sphere of influence apart from an unfree society. And as a substantive policy approach, it led to substantive results on the domestic side that wouldn't have happened had the agenda been different.

Even with two new domestic agencies, cultural policy remained, at heart, foreign policy. The semi-official modernism promoted by the government during the Cold War was never all that popular when the NEA tried to promote its appreciation at home rather than abroad. This domestic failure is best exemplified by the NEA's Works of Art in Public Places Program, which installed modern sculptures in front of government buildings in cities around the country. Commissioned artists would sometimes attempt to capture something about the local place their sculpture would occupy, but for the most part their abstract works could only evoke the most general of qualities and remained unreadable.

For instance, Guy Dill's sculpture "Hoedown," installed in 1979 in Huron, South Dakota, was meant to evoke the Great Plains' "sense of order and dependency on the weather" with four leaning rectangles intersected by logs. Locals rebelled against the installation, even organizing an "un-dedication" ceremony. They argued that, whatever Dill's intentions may have been, the sculpture was installed with no attention to the community's desires. The cosmopolitan, formalist modernism of the sculpture ignored local traditions and obstructed an organic sense of place.

The Art in Public Places Program drew similar criticism for decades, from its first installation at Grand Rapids, Michigan, in 1969 — a relative success insofar as heated public debate eventually cooled and allowed the installation to proceed — to the 1981 Manhattan installation Tilted Arc, which was ultimately removed after eight years of public pressure. Critics of the program began referring to the sculptures as "plop art" in reference to their consistent deafness to local context.

Derided in small-town and rural settings, in urban settings (where they were usually installed as part of larger urban-planning initiatives that involved erecting housing projects and brutalist government buildings) the sculptures became symbols not of urban renewal but of the coldness and decay brought by expert reorganization from afar. The program's preference for the avant-garde and tendency to employ individual celebrity artists, which was so necessary for the image that Cold War America wanted to project around the world, was simply too far removed from domestic American traditions and experience — a foreign, top-down imposition of individualism.

FROM COLD WAR TO CULTURE WAR

Our Cold War cultural policy did its job as long as the Cold War lasted. But it didn't take long after the fall of the Soviet Union for it to become incoherent to the point that we forgot we had a cultural-policy agenda. Supporting a mixture of academic avant-gardism and individual expression tailored to promote the idea of a free society as opposed to a planned one not only stopped looking like a public priority, but in the late '80s and early '90s it looked like an absolute waste of public resources.

As soon as there was no international culture war to fight, a domestic one began over Robert Mapplethorpe's erotic photography (especially one self-portrait with a bullwhip) and Andres Serrano's piece "Piss Christ" (a photograph of a crucifix submerged in what Serrano alleged was his own urine). The NEA had issued a grant to the Institute of Contemporary Art to display a Mapplethorpe exhibit, and a grant of $15,000 through an affiliate to Serrano for "Piss Christ," inevitably raising the question of why the public sector was putting money toward something so offensive and inaccessible to most Americans, or why the public sector should fund the arts at all.

While it's almost certain that Eliot would have disapproved of Mapplethorpe and Serrano, there's a degree of continuity between what he described at the birth of the U.S. government's Cold War cultural agenda and the pieces that became so controversial in the early 1990s. The NEA granted funds, directly or indirectly, to thousands of artists, but the ones that sparked controversy happened to be those that placed the artist's bodily functions at the center of the creative process. Despite stylistic differences, they placed the individual artist in the foreground of the art, in the same way that Eliot saw in Mallarmé and Valéry. The visceral presence of the artist in the process — vestigial remains of individualistic Cold War-era expressionism — carried a certain self-importance that could only fuel opposition from the "un-artistic" masses. Perhaps art less in the ethos of the elitist, individualistic Cold War paradigm wouldn't have sparked so much controversy. Domestic distaste for the official modernism became overwhelming, as did the distance between official modernism and American life.

Direct grants to individual artists ended as a result of the culture wars of the 1990s, and the NEA's budget was cut substantially, but the agency's basic function did not change. It simply began using more indirect means to do the same thing (giving funds to other organizations to give direct grants). The result was the same — ultimately directed toward artistic autonomy, a laissez-faire culture policy. Overall, the fiasco clarified that reaching for cultural influence abroad meant losing agency at home. Both sides were utterly fatalistic about what art is, about the disconnection between American culture and American life, disagreeing only over how best to "leave them alone" (whether to cut funding or to continue encouraging autonomy). Eliot's passivity had become characteristic of all mainstream views of the issue.

Both sides of that culture war completely missed the specific, historically contingent character of the NEA's function. Both saw it as a question of whether the government should support arts per se. To one side, the NEA was synonymous with pure waste, something that government has no interest being involved with; on the other side, the agency was synonymous with art itself, as if artistic priorities were necessarily the cosmopolitan academicism and personal self-expression (both equally removed from the experience of boorish Kansans who happened not to appreciate seeing their Lord in urine) promoted by Schlesinger, Greenberg, and Eliot's description of Valéry. Both sides conceded the triumph of what Eliot described as legitimate modernism, and both missed the fact that the United States has a particular cultural policy. The NEA and NEH were never meant to be neutral promoters of pure art; they had an agenda for a particular moment.

But this is not the only cultural agenda America could possibly have. The current approach was tailored to be effective in a particular global moment that has now passed. Before the Cold War, the most significant federal intervention into American culture was the Works Progress Administration, a flagship New Deal agency. The WPA's approach to culture was, in many ways, the opposite of what the government later adopted during the Cold War. Its goals were, like later iterations of culture policy, tailored for its own particular historical moment, of course. But those goals were oriented toward the domestic realm, not the foreign.

Instead of making grants to individual artists with little (explicit) care for the end result, the WPA assigned writers, artists, directors, actors, and photographers to specific projects. Cultural projects that the WPA devised were in keeping with the general purposes of New Deal agencies — it approached culture as a kind of infrastructure, attending primarily to rural areas that had been hit hardest by the disruption brought by macroeconomic forces. In addition to being hit economically by the Depression, small towns and rural areas (cultural critics of the time feared) were losing cultural ground due to the emergence of consumer goods — especially in the mass markets for entertainment represented by radio and movies, and added mobility represented by affordable automobiles — in the first decades of the 20th century.

The WPA's projects were locality-specific attempts to document folk cultures while they still existed, creating brochures and informational literature about places people might otherwise drive right past, finding not-strictly-necessary but still substantive ways to elevate the particular. Perhaps the single most important WPA cultural initiative was the Slave Narrative Collection, an invaluable historical record that collected oral histories from the last living generation of former slaves. This and other elevations of local experience ensured that folk cultures, slave experiences, and historic landmarks would all be documented not just as a jobs program but as resources for future historians, men of letters, and even consumers. This was soil for future diggers.

The WPA and its arts-specific programs launched a number of notable careers. Before he could convince radio executives to let him broadcast the "War of the Worlds" and movie executives to let him direct Citizen Kane, a 21-year-old Orson Welles took an assignment from the Federal Theatre Project (an arm of the WPA) to direct a Caribbean-set production of Macbeth in Harlem, working with local actors. The same agency also employed Welles's longtime collaborator Joseph Cotten — their first theatrical collaboration was a comedy sponsored by the Federal Theatre Project. The Federal Writers' Project, another wing of the WPA, employed Ralph Ellison when he could no longer afford his studies at the Tuskegee Institute, and gave Studs Terkel his start in radio broadcasting. The WPA's Chicago project employed a number of artists and writers previously involved in the Harlem Renaissance (including Zora Neale Hurston and Arna Bontemps) and sparked the careers of Saul Bellow, Richard Wright, and others.

The priorities of the WPA were more in line with the tradition that produced William Carlos Williams than were those of the Cold War agencies. But the WPA was not without opposition and controversy, especially regarding the proletarian preferences of many of its writers (sometimes overlapping with Communist Party membership); that's also why Cold War policy and Partisan Review taste departed from it so sharply. And it didn't last long; war and Cold War brought a new moment, and cultural policy shifted.

A LOCAL FOCUS

There has been no similar recalibration of cultural policy since the end of the Cold War. The NEA remains in more or less the same predicament it was in during the culture wars of the late 1980s and early '90s. It is a political football. The Trump administration clearly doesn't know what to do on this front; the president's budgets have proposed eliminating the NEA and NEH, and his appointee to head the NEA, Mary Anne Carter, had at the time no experience with the arts beyond driving her daughter to dance practice. The only alternatives being considered are apparently more of the same or less of the same.

But it doesn't have to be that way. The cultural problems of today are not those of the Cold War, and it's possible to recalibrate the instruments of culture policy for new problems. Today's problems are domestic: the gulf of resentment between two Americas each defined by its own mass-media bubble; loss of confidence about the future transposed onto concerns about ecology, technology, health care, and American "competitiveness"; the intrusion of consumerist and contractual attitudes into basic human relations, especially as related to children and male-female relations; loss of particular allegiances.

An administration sensitive to the ways an alliance of cosmopolitanism and individualism has not only ceased to merit public support but has contributed to today's problems is in as good a position as any since 1989 to build a culture agenda for the new moment, instead of simply eliminating its instruments. The Trump White House might have the wisdom to take a lesson from William Carlos Williams: Turn your attention homeward, to the soil, to the local and regional. That's where agency is possible, allegiances are built, roots are grown, and the future is decided.

An America First culture policy doesn't have to start from square one. To the NEA's credit, it directs a number of programs designed to work with small towns, such as "Our Town" grants — a "creative placemaking" program that works with municipal governments to integrate the arts with infrastructure projects. Such initiatives always run the same risks that the Art in Public Places Program did, and it may take several years to clarify how well these grants actually produce things people can live with, but the program could very well be compatible with whatever comes next.

In addition, NEA grants are often allocated to local arts councils (often on their way to funding individual artists for projects not overseen by the NEA). But these are simply indirect ways to pursue the same priorities that the NEA has historically advanced. A small-scale focus should become central. Only 13% of NEA-supported activities in 2017 took place in rural communities (according to the agency's latest annual report), and given that 100% of mass culture flows from urban to rural America and is produced by people who tend to resent the latter, that ratio needs to change.

But there are also historical sources for inspiration. It would be beneficial to internalize some lessons from the WPA era. Above all, it's crucial to see that the national cultural interest is not neutral. How the state chooses to support the arts, even when it chooses a laissez-faire approach, has tangible results distinct from those of other choices, and so it's possible for a laissez-faire approach to not be the best choice for the times. At such moments, it can be beneficial to commission particular projects instead of promoting individual celebrity-artists. The government no longer has a strong interest in impressing the world with America's boundless freedom of expression. A more important activity for instruments of culture policy is the building (or rebuilding) of cultural infrastructure, and the development (or redevelopment) of a common American tradition.

The WPA is also a good model for some of the kinds of projects that would be worth public-sector support. As with slave narratives, collected oral histories of the Greatest Generation could be an important historical resource in the future. Memory is a vital part of any cultural infrastructure; collecting memories helps generate a common historical consciousness to draw on to help face the future — knowing what our recent ancestors overcame and how. For similar reasons, the restoration of historic structures, from churches to municipal buildings — not only those that have been subject to natural decay, but those that have been "renovated" or simply demolished and rebuilt according to modernist taste — could be a priority. "Outdated" architecture can ensure that the places where people live have built-in memory and particular character.

Of course, there may be no better way of building a mass of memory and encouraging attention to local particulars than subsidizing the return of local newspapers. Local papers might help attract talented liberal-arts students back to their hometowns, undercut the stranglehold that mass-media outlets have on public attention, encourage print reading, and provide still another resource for future Eliots. There may be no better time for the federal government to offer such support, while a fair number of papers still exist and former editors of now-closed papers are still alive.

Direct grants are still plausible, as long as the government is clear about what it wants to achieve. At the moment, cultural communication, values, and artifacts all flow from urban to rural America, and a top priority has to be making that one-way flow of communication two-way. Imagine a grant program in which the NEA sends young aspiring artists to rural locations and shrinking, struggling small towns for an extended period of time in exchange for college-debt relief. It would require participants to use their preferred medium to document the people they're around, instead of artificially romanticizing, politicizing, or disparaging them from a distance. The program would likely have to attach some strings to encourage attention to, and respect for, local detail: limit cellular phone use, make participants live with a local resident, require attendance at church or work or other activities with their hosts, all on penalty of forfeiting the debt relief.

BEYOND COSMOPOLITANISM

It is important that these or any other new initiatives are not just added on to already-existing policy. They must replace it altogether. What's most needed is a clear shift away from the cosmopolitan individualism of the past half-century, and it does no good to perpetuate an old paradigm that undermines the new one.

Such a shift would be consistent with the American tradition. The ability to see the transcendent in the familiar and the particular has formed an important tradition in American letters since Walt Whitman and Herman Melville. Williams followed in this tradition, which has been referred to as "democratic modernism" and "cultural nationalism" and reached perhaps its best defense with the "Young American" critics of the early-20th century, as historians Casey Blake, Jude Webre, and others have documented. These historical resources are still available to inspire a new shift.

Recently, traditionalism in America has tended to mean following Eliot into Anglo- or Euro-philia. Encouraging distinctly American artistic habits stands a chance of making art more accessible without making it unserious or "middlebrow." The arts are so irrelevant to most Americans' lives in no small part because they have diverted so sharply from that tradition. Without reconnecting to the "soil" of the life experience of most Americans, the art world exists with and for the Hamptons.

Using the existing instruments of culture policy to bring about a new paradigm in American culture policy is more likely to produce positive results than simply cutting the whole thing. There is no guarantee, of course, that a suite of new government programs would change American culture, but it only takes one masterpiece to move the arts in a new direction, as Williams noted about The Waste Land.

According to Williams, the quest for international influence has led to an evaporation of agency — the only way anyone can think about culture is to sit back, not get involved, let it happen. That is no less true of public culture policy than it was of Eliot. But again, the realm of local experience is where agency can be restored. It's time to return to the national project of building up the mass in which some future Eliot will dig.